Tags

Appalachia, crime, culture, feud, genealogy, Harts, history, life, Lincoln County, photos, West Virginia, Will Adkins

02 Saturday Nov 2013

Posted in Lincoln County Feud

Tags

Appalachia, crime, culture, feud, genealogy, Harts, history, life, Lincoln County, photos, West Virginia, Will Adkins

02 Saturday Nov 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Appalachia, Billy Adkins, Boone County, Chloe Mullins, Clintwood, crime, Ed Haley, history, Hollene Brumfield, Imogene Haley, slavery, Solomon Mullins, writing

After talking with Lola, we walked down the street with Billy Adkins and spent a few hours filtering through genealogy books at his kitchen table. Billy, I discovered, had two large bookcases filled with categorized three-ring binders dedicated to Harts families. One of the first things we dug out were notes pertaining to Ed’s mother, Emma Jean Haley. Years earlier, Lawrence Haley had told me that someone shot her in the doorway of what I later learned to be Al Brumfield’s house. In his notes, Billy recorded her as re-marrying James Benton Mullins, a son of Peter and Jane Mullins, which we ruled out immediately: James B. was her uncle. The Emma who had actually had married this fellow was born in 1876 (about eight years after Emma Haley) and was listed in other sources with the maiden name of Johnson.

“I don’t know where I found that out but somebody told me that that woman right there was Milt Haley’s widow,” Billy said. “But that date’s totally wrong, see.”

Whether or not Ed’s mother had ever remarried anyone, based on census information, Brandon was convinced that she had died in the 1890s. In the 1900 Logan County Census, her mother Chloe Mullins listed seven of her nine children as being alive. The seven accounted for were Joseph Adams, John Adams, Ticky George Adams, Peter Mullins, and Weddie Mullins. The two who were not listed in the 1900 census were Dicy (Adams) Thomas, whose husband was listed as a widower in the census, and Ed’s mother.

We found out from Billy’s notes that Emma Haley descended from a notorious counterfeiter named Solomon Mullins.

“Money Makin’ Sol,” as he was called, was born to John and Jane Mullins on the Broad River in North Carolina in 1782. Around 1806, he married Sarah Cathey; he settled in Kentucky by 1810.

“Solomon was always ready for action,” according to photocopied papers at Billy’s house. “He served in the War of 1812 in Cpt. David Gooding’s Company of Kentucky Volunteer Militia. After the war, Solomon, evidently ready for more action, began counterfeiting coins. Family tradition has it that Solomon found one of John Swift’s ‘Lost Silver Mines’ in the hills of eastern Kentucky and ‘South of the Mountain’ in Southwestern Virginia. Thus he became known as ‘Money Making Sol’, and I might add always the ‘genius’, stayed one step ahead of his trouble. In 1837 Solomon decided to join his father and his two brothers in Russell County. He bought a farm and built a shop just a little ways from his house where he began making money again. He melted the silver down and didn’t seem to care who saw him.”

“I was born August 29, 1840, at my father’s home below Clintwood,” according to a 1926 interview with one Nancy Mullins. “The Mullins mixed with the Indians. I have heard it said that Grandpa John Mullins was about one-fourth Indian. Grandpa John had at least two brothers. One was named Sol and he owned a lot of slaves. He was a moneymaking man. He lived on the other side of the branch in a bottom near my father’s home. He had a crowd of slave wenches. He made money on Holly Creek back of Press Harris’ home. He had his work place under a cliff. Pa and Uncle John used to help him work at this business. They would ‘strike’ for Sol. While they lived there, his slave women would take guns and go hunting. They would kill deer and pack them in on their backs. The government got after Sol and he went to West Virginia where he died.”

“Solomon Mullins moved to the waters of Holly Creek, about two miles northeast of Clintwood, [Virginia,] where he lived for several years,” according to Sutherland’s The Mullins Family in Dickenson County (1967). “He owned several slaves, mostly women, who worked in the fields and hunted in the woods. He made counterfeit money for several years under a cliff near Holly Creek. The cliff is still pointed out by neighbors as ‘Sol’s Cliff.’ He was caught at work once by a detective and when he saw he was caught, he ordered the detective to help him work, saying: ‘Grab that hammer and strike this.’ He hoped this would make the detective afraid to tell on him, but it didn’t do any good. He managed to get pure silver and mixed other metal with it to make the counterfeit money. He would pay $2 of his counterfeit money for $1 of the government money. At last, he took a scare and left this country.”

In 1837, Sol and his son Peter were involved in making counterfeit coins in Russell County, Virginia. As a result, according to Boone County, West Virginia, History (1990), they moved to Marion County, Tennessee, where they renewed their counterfeiting activity. In the winter of 1841-42, after pressure from government authorities in Tennessee, Sol and Peter moved with their families and slaves to the North Fork of Big Creek in Logan (now Boone) County, (West) Virginia.

“They rode mules and walked all the way,” according to Boone County. “He died in 1858 and Sarah died about 1872.”

As Brandon flipped through the Sol Mullins notes, I could see his brain working, making connections. Suddenly, he said, “Sol was a great-grandfather to both Emma Haley and Hollena Brumfield…making them third cousins.”

Oh my.

01 Friday Nov 2013

Posted in Fourteen, Wewanta, Women's History

Tags

Appalachia, Caleb Headley, Elizabeth Jane Farley, Fourteen, Fourteen Mile Creek, genealogy, history, Lincoln County, midwife, photos, Sarah Headley, Sulphur Spring Fork, U.S. South, West Virginia, William Floyd Farley

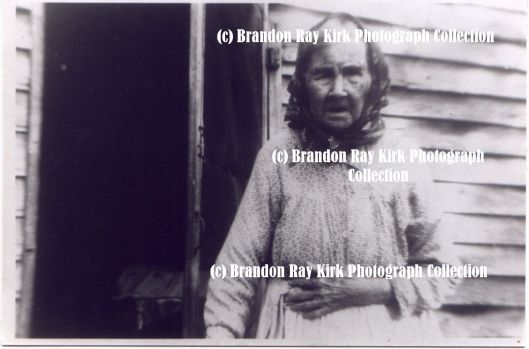

Sarah Ann (Farley) Headley, daughter of William F. and Jane (Clark) Farley and wife of Caleb Headley. Sarah (1849-1945) is my great-great-great-grandmother. She lived at Sulphur Spring Fork of Fourteen Mile Creek in Lincoln County, WV.

01 Friday Nov 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Appalachia, Billy Adkins, Cain Adkins, Cat Fry, crime, feud, George Fry, Green McCoy, history, Lola McCann, Milt Haley, Vinnie Workman, writing

Before heading to Billy’s, we became knee-deep in conversation about Milt Haley’s death. Billy told us about the Brumfields retrieving Milt and Green in Kentucky.

“Now, I don’t know where they come from over there,” he said. “I know they had a bogus warrant, the people that went to get them. They made up a fake warrant and got them. Then when they started back down through here, they was a big bunch of people was waiting to attack them. That was Cain Adkins and them and his family. They was fields full of them up on Big Branch. And somebody tipped them off, and so they went up what’s called Bill’s Branch. And so they took up Bill’s Branch and down Piney and then over to Frank Fleming holler.”

From Frank Fleming hollow, the Brumfield gang went over a mountain and crossed the river to a Fry house near the mouth of Green Shoal. At some point, according to Lola, a group of men came in and shot out the lights. Cat Fry crawled under a bed while either Milt or Green shouted to the other, “Stand up and die like a man!” Lola heard that one of the men “died a praying and the other died a cussing.”

I asked Billy if he’d heard how Milt and Green were killed.

“I’ve heard so many stories, I don’t know,” he said. “I just heard they was shot. I heard they was tied up to a tree. Tied to a chair back to back in the kitchen.”

Lola said she heard that Milt and Green were shot and hung.

“The table Milt and Green had their last meal on ended up with my grandmother, Vinnie Thompson Workman,” Billy said. “And there was bullet holes in the table.”

I asked Billy if he had any pictures of the “murder house” and he said, “No, I don’t know of anybody would. It’s where Doran’s house is. It was over there against the hill — an old log house. Of course, the railroad and stuff wasn’t there, you see. That was the old John and Catherine Fry house to start with. And then John’s son Baptist, he lived there next. That was my grandmaw’s grandpaw. And after he died, I guess this George Fry lived there. Charley Fry and George Fry both lived there and I don’t remember which one lived there when they killed them there.”

At that point, Lola completely changed the direction of the conversation when she said, “Billy, Cain Adkins was kin to us.” She’d never met Cain and had no clue what happened to him but knew that he once owned most of the lower end of West Fork at one time. All the old-timers referred to him as “Uncle Cain” because he’d been a well-respected person in the community.

Lola said George Thomas (one of Ed’s cousins, we later learned) owned the Cain Adkins farm in the years prior to her birth. Her father bought the place from him around 1905. At that time, the only remnant of Cain’s life there was his apple orchard by the creek. The Haley-McCoy grave was on the family lands.

“You go up almost to the top where it gets real flat,” Lola said. “They’s a path used to be up there. It’s up pretty much on the hill. It ain’t way up there, I’d say the first flat.”

Brandon asked her, “Now, did you tell me that some old woman used to come up there and decorate that grave?”

“They always came as long as they lived, I guess, and decorated the grave,” Lola said. “That was their wives. I was only four or five years old, but I can remember seeing them. One of them was tall and slim. But they stopped at our house every time they come.”

31 Thursday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Al Brumfield, Bill Adkins, Billy Adkins, Cain Adkins, fiddle, Green McCoy, Harts, history, Hollene Brumfield, Jackson Mullins, Lola McCann, Milt Haley, writing

That night, Brandon suggested visiting Lola McCann, a local widow of advanced age. Lola, born on the West Fork of Harts Creek in 1909, lived in Harts proper, just back of an old hardware store, a video store, and the post office. She spent a lot of time with her daughter Cheryl Bryant, who lived across the street with her family. We found Lola at her daughter’s home almost buried in the cushions of a plush couch. As everyone made introductions, I headed over and sat down beside of her.

When Brandon asked Lola about the old Al Brumfield house, she said it was haunted, that Hollena Brumfield had kept the clothes of deceased relatives in an upstairs closet (top-story front downriver side). She never would spend the night there. She said the staircase was stained with blood and five or six bodies lay down in the old well. This all sounded like folk tales, the type of stories to tell in an old cabin around the fireplace…but who knows?

As things kinda moved along with Lola, Brandon mentioned that we should be sure and visit Billy Adkins, a neighbor and expert on local history and genealogy. Lola’s daughter immediately called him and invited him over. The next thing I knew a little stocky guy with a shaggy beard arrived at the door. It was Billy, of course, holding a fiddle, which he said belonged to his father Bill Sr., an old fiddler in Harts.

I told Billy that his father just had to know Ed Haley but he said, “I asked him and his mind’s gone. He can’t remember. He’s got Alzheimer’s. His mind just comes and goes.”

Bill, Sr. had given up the fiddle in recent years, but Lola’s daughter had a short home video of him playing “Bully of the Town”, “Way Out Yonder”, and “Sally Goodin” in 1985. Bill’s style was completely different from what I pictured as Ed’s — he held the bow toward the middle and played roughly with a lot of double-stops — but I was still anxious to talk to him. Billy said we could see him the following day as he was already in bed asleep.

When we mentioned our interest in the 1889 troubles, Billy said, “Green McCoy married Cain Adkins’ daughter. Cain and Mariah. Mariah was a Vance, I think. And they lived where Irv Workman’s house is now.”

Brandon asked, “Which is near where they’re buried, right?” and Billy said, “Yeah, right across the road from it. And Milt Haley married Jackson Mullins’ daughter. Jackson and Chloe Mullins, from up on Trace. She married again.”

What? Ed’s mother remarried after Milt’s murder?

“I believe it was another Mullins,” Billy said, “but I’d have to look it up. Milt’s name was Thomas, you see.”

It was all in his notebooks at home, he said, although he warned us: “See, I didn’t document any of this stuff. I didn’t put my sources down and when I’d run across it I’d just write it down. Now, I don’t know how I found it out.”

30 Wednesday Oct 2013

Posted in Ferrellsburg

Tags

Arena Ferrell, Charley Brumfield, Charlie Conley, Ferrellsburg, George W. Ferrell, history, Irene Mitchell, Keenan Ferrell, Lula Fowler, music, The Lincoln County Crew, The Murder of John Brumfield, writing

Keenan S. Ferrell, the adoptive father of George W., had been born in March of 1854 to George and Nancy (Farley) Ferrell in Boone County. He appeared in the 1860 and 1870 censuses for that county in the home of his parents. On April 6, 1877, in Logan County, he married Arena Sanders, a daughter of Martin and Elizabeth (Mitchell) Sanders. Arena, or Rena as she was called, had been born in March of 1861 in Russell County, Virginia. In 1880, the Ferrells lived in the Logan District of Logan County.

In the late 1890s, Keenan and Arena Ferrell moved to the Harts area of southern Lincoln County. In 1895, Rena bought 75 acres of land at Fry, on the east side of the Guyandotte River, from Admiral S. Fry, an early landowner and postmaster at Green Shoal. The following year, she bought 70 more acres on the west side of the river from John Q. Adams. In 1897 she bought a portion of the old Elias Adkins estate, situated on the river between Harts and Green Shoal. Upon this latter piece of property she erected a store building and, in short time, the surrounding area became known as Ferrellsburg. By 1900, the Ferrells had acquired George W., whom they reportedly adopted. Census records for that year show him as an “adopted son.”

Also in the home in 1900 was Lula Vance, the seven-year-old orphaned daughter of John and Columbia (Kirk) Vance. Lula would have practically grown up in the Ferrell home at the time that George W. lived there. Strangely, she never spoke about him to her children. “I don’t remember Mommy ever mentioning anything about George Ferrell,” said daughter Irene Mitchell, of Harts, in a 2003 interview. “That’s kind of strange since Mommy would’ve been raised with him. But she never really talked much about staying with the Ferrells.”

George Ferrell spent his twenties as a bachelor working around the store and making music. He was postmaster at Green Shoal from December 22, 1902 until December 26, 1904, when the office was discontinued to Ferrellsburg. He is credited with the authorship of “The Lincoln County Crew” and “The Murder of John Brumfield,” as well as a song about someone named Harve Adkins. In composing “The Lincoln County Crew,” Ferrell borrowed heavily from “The Rowan County Crew,” assuming this latter tune — documenting events of the Martin-Tolliver Feud in Kentucky — was written first. Ferrell’s version of the song, which primarily draws on local events that happened in Harts between 1889 and 1891, is a warning for men to stop drinking or risk a young, violent death.

“The Murder of John Brumfield” details Brumfield’s murder by Charlie Conley at a Chapmanville Fourth of July celebration in 1900. There is a story that Ferrell was playing this latter song for a crowd of people near the Ferrellsburg train depot when one of Conley’s brothers passed through. According to the story, Ferrell ceased his playing and singing because he feared his tune might cause trouble. But one of the attendants, Charley Brumfield, a brother to the slain John Brumfield, told him to keep the song going — no one would bother him. As Ferrell continued his music, Conley made his way by and on across the river toward his home on the Smokehouse Fork of Big Harts Creek.

George W. Ferrell died on August 6, 1905 at the age of 30 years, reportedly of tuberculosis. His tombstone offers this Biblical quote: “In my father’s house are many mansions.” Also on the stone is the following epitaph:

His last words were Mamma come to me. God bless you. Cease your mourning. Cease to languish o’er the graves of those you love. Pain and death and night anguish, enter not the world above. Sight and peace at once deriving from the hand of God most high. In his glorious presence living, they shall never, never die.

Years later, Fred B. Lambert, noted genealogist and regional historian, published “The Lincoln County Crew” and “The Murder of John Brumfield” in his 1926 edition of The Llorrac. His private notes, now in the hands of the Special Collections Department at Marshall University’s Morrow Library, contain slightly different versions of “The Lincoln County Crew,” as well as a reference to the tune Ferrell wrote about Harve Adkins.

30 Wednesday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Ben Adams, Charlie Curry, Ed Haley, feud, French Bryant, history, Hollene Brumfield, John Martin, Mae Brumfield, Robert Martin, Tom Brumfield, Wesley Ferguson, writing

Brandon asked Mae what else she’d heard from the family about Al’s trouble with Milt and Green.

“All I’ve ever heard them talk about is going and getting them fellers that shot him and her, over in Kentucky,” she said. “They was just a posse went — I don’t know who they were — they rode horses and went to Kentucky and hunted these men. They caught them and they brought them back I guess and put them on their horses. I think that’s the way Granny told it to me. The river was up, and they tied them to horses and had somebody on the other side to catch them when they come across. Run them horses across that river with them to the other side. That’s how they got them and brought them up here to Fry.”

Now how did they get possession of them?

“Wasn’t some of the law men with them?” Mae asked. “I think now they was some law had them, and they claimed they took them away from the law. They never did discuss it too much to me. I’ve just heard outsiders talk about it.”

Mae said the Brumfields and Dingesses made life hard on Ben Adams after hearing that he’d been the one who hired Haley and McCoy. One night, they set his house on fire and tried to flush him out into the yard so they could shoot him. His wife, hoping they wouldn’t hurt her, ran outside repeatedly and extinguished the blaze. She begged the Brumfields and Dingesses to leave them alone for her sake and that of her children, and promised to take the family away the next morning if they were spared. The attackers were apparently satisfied because they left Ben Adams alone afterwards.

I asked Mae if she knew French Bryant and she said, “Yeah, I knew French Bryant. He was one of the gang, they said, I don’t know. I wasn’t acquainted with him — seen him pass here.”

Brandon asked Mae what it was like at Hollena’s house in her time there.

“Well, the family just practically came in and out all the time,” she said. “Tom’s mother lived here in a little old three-room house, and she stayed down there. Ward was a manager — that was her husband — Tom’s daddy. He managed her till he got killed. They all just practically lived at home. Hendricks lived up in the bottom over in Harts. At daylight, him and his family come down here — every day, they never missed a day. The family helped cook. Just always a big crowd there.”

Brandon asked if Hollena ever did any cooking.

“Oh, no,” Mae said. “She couldn’t work. She was crippled up too bad. She hired people to stay with her, and then Tom’s mother stayed there and done the work a lot. I never seen her cook none but one Sunday. Everyone had gone somewhere and me and Tom had come over there. And me and her and Wesley — her husband — and Tom was the only ones there. And she said, ‘Me and Mae’s gonna cook dinner. Tom go out there and kill me one of them big fat hens. Gonna make me some homemade dumplings.’ I’d never made no dumplings. That’s just right after we’d got married. I said, ‘Granny, I don’t know how to make dumplings.’ ‘I’ll teach you. I know how.’ Buddy, she did. She made the finest pot of dumplings you ever ate. She’d tell you how to cook. She knew all about it.”

I wondered if Hollena liked to have music in her home.

“I never did see no music,” Mae said. “I don’t know whether she liked it or not. She didn’t even have records probably. Had an old organ. I guess some of her girls mighta played it, you know. They was married and gone when I come into the family.”

Two local fiddlers, Bob and John Martin, sometimes came around and played for Hollena’s boarders. At these gatherings, there was moonshine for everyone (including Hollena, who liked to nip).

Mae heard that Milt Haley’s son — a blind fiddler — once had dinner there.

“His son, Ed Haley, come down there at Granny’s,” she said, catching me totally by surprise. “He played music, and he’d been around here playing music. He was down there around the mouth of the creek somewhere around her home, and she made them bring him in and feed him dinner. She didn’t hold no grudge. I’ve heard them tell it. I think maybe he stayed around in the community here. They used to have — I’ve heard them talk about it — them old dances around on Saturday nights. See all I know I’m telling you is just hearsay, something that somebody told me.”

Brandon asked Mae about Hollena Brumfield’s death. Mae wasn’t sure exactly what killed her.

“Supposed to been old age,” she said. “I don’t know whether she had any other problems or not. She was sick. Not long — one or two weeks.”

Brandon asked, “Did Hollena make any confessions or give any advice on her deathbed?”

Mae said, “I wasn’t a Christian at that time and I never asked her no questions like that. I don’t know whether she ever belonged to any church or not.”

Brandon said, “Somebody told me that right before she died she wanted a preacher named Charlie Curry to see her.”

“Probably did,” Mae said. “I don’t know. She may have.”

Charlie Curry, I remembered, was the preacher who once refused to baptize Ed Haley because he was drunk and wouldn’t give up playing the fiddle.

28 Monday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Al Brumfield, Ben Adams, Charley Brumfield, feud, Green McCoy, Harts, Hollene Brumfield, Jane Thompson, John W Runyon, Mae Brumfield, Milt Haley, timbering, writing

After a brief rest at Mr. Kirk’s, Brandon and I drove to see Mae Brumfield at her little yellow house just up the creek from the bridge at Harts. Mae was one of Brandon’s special friends, a woman of advanced years and closely connected to the Brumfield family. As a girl, she was a close friend to Charley Brumfield’s daughters. Later, she married Tom Brumfield, one of Al’s grandsons, and settled near his widow — “Granny Hollene” — at the mouth of Harts Creek. Just back of her house was the former site of the old Brumfield log boom, as well as the spot where Paris Brumfield killed Boney Lucas.

Mae welcomed us inside as soon as she saw Brandon. She was very thin and frail — a wisp of a woman — but she seemed to be very independent and self-sufficient. Her house was tidy and there were several crafty-type dolls in sight as evidence of her fondness for crocheting and knitting. Almost right away, Brandon asked her about Hollena Brumfield — the woman supposedly shot by Milt Haley.

“Granny Hollene?” Mae said. “Why, I’ve combed that old gray head many a time. I loved her better than anything. She wasn’t afraid of nothing. She’d cuss you all to pieces if you done something to her but she was a good person. Everybody was welcome at her table. She didn’t turn nobody away. You know that hole was in her face where those men shot her. It never was worked on. They didn’t have plastic surgery like they do now. And after all that, a sawmill blew up and broke her leg. That was why she was crippled. And she still run everything on.”

Mae told us what she knew about Al Brumfield.

“I’ve heard Grandpa talk about him. Grandpa liked him. Al Brumfield, my grandpa said, was an awful smart man. He told me he was a good-looking man. He was sort of blonde-headed and had blue eyes. People said he could take a dollar and turn it into a hundred in no time. Al Brumfield today woulda been a millionaire. He owned up to Margaret Adkins’ farm where the Ramseys used to live around there. Back this way, he owned all that property over in yonder where the Chapmans lived. He owned up this creek to Big Branch, all back this way, all them bottoms up through yonder and where I live and clear on down to Ike Fry Branch — maybe to Atenville. He had sold that to Charley, I think, his brother.”

We asked about Al’s trouble with Milt Haley and Green McCoy.

“People timbered then for a living, you know,” she said. “Well, Al put that dam in across the creek here or on down there somewhere — a boom. These people drifted their timber down here when they come a raise to they could get it out. Al went to the government and got a charter to put this dam in and caught the timber. He’d catch the logs and charge people so much for catching their timber. I don’t know whether it was ten cents or a quarter. It wasn’t very much. They’d come down here then and raft them and then run them on down to Huntington and sell them. That’s what the startation was, I think, of this killing. A lot of these men up the creek, you know, they was like today. They was prejudice in families and jealousy and he was building up good, you know. Had plenty. And they didn’t want to pay that toll. And they didn’t like him. They was the ones that hired this Haley and Green McCoy.”

Brandon asked Mae who specifically hired Milt and Green and she said, “I think it was Adamses. Now I won’t tell you for sure. Old Ben Adams was one. They didn’t like him. They called him ‘Old Ben Adams.’ He lived way up this creek somewhere. Them Adamses shot at Al’s gang up here somewhere back in the beginning about this timber. I think they tried to kill him out then. That’s why they wanted rid of him was on account of him catching timber and they was enemies. But Adams wouldn’t do it hisself — he hired these two men — and that’s what caused it, so I understood.”

So John Runyon wasn’t the one who hired them?

“No, I believe he owned the mouth of this creek, didn’t he, and Al bought it from him? He’s the man that owned the store… I don’t know how much of this land he owned — just the mouth of this creek, I’ve heard them say. I guess Al bought all this other property.”

At the ambush, Hollena hollered for Al to run because she knew he was the target of the men shooting at them. Al retreated for a short time before coming back up the creek firing a pistol toward his would-be assassins, but was unable to hit them due to heavy growth on the trees. Milt and Green fled into the woods, at which time “old Jane Thompson” came to Hollena and “got her up.”

26 Saturday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Al Brumfield, Brandon Kirk, Dingess, feud, Harts Creek, history, John Hartford, Lawrence Kirk, Tug River, Twelve Pole Creek, Weddie Mullins, West Virginia, writing

The next day, Lawrence’s son drove the four of us over to Inez, a small settlement on the Tug River and the seat of government for Martin County, Kentucky. According to written history, Milt and Green were captured and jailed there in 1889. We made our way to the courthouse, which was surrounded by a few interesting buildings where Brandon darted inside to seek out some record of Milt and Green’s incarceration. Unfortunately, many such records had been lost in an 1892 fire. (It’s said there’s nothing more convenient than a good courthouse fire.)

Just before we left town, Lawrence said, “Well, straight east from here at this courthouse about eight miles across the river is the mouth of Jenny’s Creek on the West Virginia side. That’s approximately the way they traveled with these people when they left Kentucky. They went up Jenny’s Creek out the head of Jenny’s Creek into Twelve Pole and out of Twelve Pole down Henderson Branch into Big Harts Creek. It’s a direct route through there. We’re goin’ to be traveling approximately that. We’re going to be going around some places on account of the road but we’ll come back to the mouth of Jenny’s Creek over there.”

As we crossed the Tug into Kermit, Lawrence said, “I don’t know how far they would travel in a day by horseback through these trails on these mountains but they would travel a long ways. I think they did it in a day from up here at Kermit. Yeah, they’d do it in a day.”

Lawrence directed us up Marrowbone Creek and over to the little town of Dingess on Twelve Pole Creek. He said the posse never came through there with Milt and Green but it was the closest we could get to their trail due to the layout of current roads. Dingess, I remembered, was the place where Ed Haley’s uncle Weddie Mullins was murdered in a shoot-out at the turn of the century. The little town was reportedly named after a brother-in-law of Al Brumfield.

The next big thrill was navigating cautiously along a gravel road and entering Harts Creek at the head of Henderson Branch. We followed that branch to its mouth then went on down the main creek past Hoover, Buck Fork, and Trace Fork before turning up Smoke House Fork. Lawrence guided us past Hugh Dingess Elementary School to the site of Hugh Dingess’ old home at the mouth of Bill’s Branch. He said the posse took Milt and Green up Bill’s Branch, over the mountain, and down Piney Creek. They followed Piney to its mouth, then went up West Fork to Workman Fork. From Workman Fork, they crossed the mountain to the Guyandotte River. We were only able to drive part of this latter leg of the trip.

25 Friday Oct 2013

Posted in Ferrellsburg, Women's History

25 Friday Oct 2013

Posted in Big Ugly Creek, Ferrellsburg, Music

Tags

Archibald Harrison, Arena Ferrell, Big Ugly Creek, C&O Railroad, Cleme Harrison, Daniel Fry, Don McCann, Ferrellsburg, genealogy, George W. Ferrell, Guy Harrison, Guyandotte River, Guyandotte Valley, Harold Ray Smith, Harts Creek District, history, Keenan Ferrell, Laurel Hill District, Lincoln County, Logan County, Martha E. Harrison, Martha Harrison, music, Nancy Fry, Nine Mile Creek, Phernatt's Creek, Tazewell County, Virginia, writing

Around the turn of the century, in the years just prior to the arrival of the C&O Railroad in the Guyandotte Valley, George W. Ferrell, a musician in present-day Ferrellsburg, busily wrote songs about local personalities and events. Today, Ferrell’s solitary grave is marked with an ornate tombstone that sits at the edge of what was, until recent years, a garden.

George W. Ferrell was born on October 10, 1874 to Archibald B. and Martha E. (Fry) Harrison. Archibald was the son of Guy P. and Cleme (Harmon) Harrison of Tazewell County, Virginia. Mary was the daughter of Daniel H. and Nancy P. (Bailey) Fry of Logan County. Ferrell’s birthplace is not known because, soon after his parents married in 1865, they left the area, settling at first in Kentucky and then elsewhere.

In 1878, George, then four years old, returned to Lincoln County with his parents. In 1880, his family lived near the mouth of Big Ugly Creek or at the “Bend,” just across the Guyandotte River. Shortly thereafter, they made their home at Phernatt’s Creek, further downriver in Laurel Hill District.

By 1889, Ferrell’s father — who was perhaps recently divorced from his mother — had sold all of the family property in Harts Creek District and at Phernatt’s Creek and relocated to Nine Mile Creek.

Details concerning Ferrell’s early life remain elusive. It is not known who influenced him musically or when he even started writing or playing music. There is no indication of his father or mother being musicians but his mother’s first husband, Jupiter Fry, was a well-known fiddler on Big Ugly. Some of his first songs may have been inspired by his father’s stories of the Civil War.

At some point in his young life, and for reasons unknown, Ferrell was adopted by Keenan and Arena Ferrell, a childless couple at Ferrellsburg in Lincoln County.

“I heard he was just a big old boy when the Ferrells took him in,” said Don McCann, current owner of the property surrounding Ferrell’s grave. “They didn’t have any children of their own.”

In the 1900 Lincoln County Census, Ferrell was listed as their 25-year-old adopted son. More than likely, he was assisting the Ferrells in the operation of their store and business interests.

It is easy to see how Ferrell would have become acquainted with his future foster parents.

“His father worked a lot of timber around Big Ugly or Green Shoal,” said Harold R. Smith, Lincoln County genealogist and historian. “And that would have put him in close contact with the Ferrells at Ferrellsburg.”

But why was he not living with his mother (wherever she was), who died in 1901, or his maternal grandmother, who was alive on Big Ugly? And what was his connection to the Ferrells?

25 Friday Oct 2013

Posted in Harts, Women's History

25 Friday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Bill Brumfield, Branchland, Ed Haley, Ferrellsburg, fiddling, history, Isaiah Mullins, Lawrence Kirk, Lincoln County, Mildred Cook, music, Paris Brumfield, writing

That evening, Brandon and I went to see Lawrence Kirk at his nice single-story home on Fowler Branch in Ferrellsburg, West Virginia. We sat around the kitchen table where Lawrence pulled out a map of the Tug Valley and showed us the route taken by the Brumfield posse after they apprehended Milt and Green in Kentucky. We made plans to re-trace the route the next afternoon.

I said, “Of course, they had to ford back and forth at the low water mark of the river. They were on horseback weren’t they?”

“Yeah, they rode horses back through there,” Lawrence answered.

I asked, “Do you reckon they had Green and Milt on the same horse or on different horses?”

“I figure they had a horse for all of them,” he said.

Reckon they had their hands tied?

“I imagine they did.”

Brandon asked if Lawrence’s grandfather Bill Brumfield had been in the Haley-McCoy mob. He was a younger brother to Al and a teenager at the time of the killings.

“Never did know,” he said. “I doubt that he was. I believe I’d a heard something about it. See, he was pretty young at the time.”

Bob Adkins had remembered Bill as a “mean old devil,” and most people around Harts said he was the roughest of Paris Brumfield’s sons.

“The old man, as bad as he was to fool with that liquor, he tried to keep order, but he’d get drunk hisself and he’d get out of hand, see,” Lawrence said. “Well, his son — my uncle — my mother’s brother — shot him and killed him. They said they was just on a big binge there at my grandfather’s.”

At midnight, we were still huddled around Lawrence’s kitchen table talking and looking over maps when Brandon’s mother showed up wearing flannel pajamas with a letter from Mildred Cook of Branchland, Lincoln County. According to the letter, Mildred was the daughter of Isaiah Mullins and a cousin to Ed Haley.

“I remember when Mr. Haley came up Little Hart and played the fiddle for me, my two brothers, sister and My Dad,” the letter partially read. “He had a little boy with him about 8 years old. Mr. Haley came to our house 1931. I was 11 years old. He was just visiting when he come to our house. He was there approx. 2 hours. The Best I can remember Ed Haley played ‘Wildwood Flower’ and ‘Turkey in the Straw.’ He went on up little Harts Creek after he stayed and talked a while.”

21 Monday Oct 2013

Posted in Culture of Honor, Ed Haley

Tags

Bill Brumfield, Bob Adkins, Brandon Kirk, Charley Brumfield, crime, Eustace Ferguson, Harts, history, Hollene Brumfield, John Hartford, Lincoln County, Paris Brumfield, Wesley Ferguson, West Virginia, writing

In thinking about the old Brumfields, Bob mentioned the name of Paris Brumfield, the patriarch of the clan. Brandon quickly pulled out Paris’ picture and reached it to Bob saying, “He was my great-great-great-grandfather.” Paris, we knew, was murdered by his son Charley in 1891.

“Son, he was a mean old man, I’ll tell you that,” Bob said, turning the picture upside down in his hands and slowly studying it under a magnifying glass. “He’d kill anybody. He beat up on Charley’s mother and she went down to Charley’s for protection. He went down to get his wife. He got up to the top of that fence and Charles told him, ‘You beat up on Mother the last time. You’re not coming in here.’ Paris said, ‘Ah, you wouldn’t shoot your own father.’ Drunk, you know. And Charley said, ‘You step your foot over that fence, I will.’ Directly he started in and that there ended it, son. Charley killed him right there.”

I said, “Now there was another Brumfield father-son murder later on. Who was that?”

“Ah, that was Charley’s brother,” Bob said. “Bill Brumfield, up on Big Hart. He’s a mean old devil. He ought to been killed. He had a way… He never shot anybody. He’d beat them to death with a club. He’d hold a gun on them and make them walk up to him and then take a club and beat their brains out. He come down there to Hart to get drunk once in a while and he’d run everything away from there. And Hollene set on that front porch of that little old store she had out there with that pistol in her apron and she cussed him. He knew she had that gun — he wouldn’t open his mouth to her. It was his sister-in-law, you know. He just set there and chewed his tobacco and spit out in the street. She’d tell him how mean he was, you know. But his own son killed him. He was beating up on his mother and you can’t do that if you got a son around somewhere. I don’t give a damn who you are, they’re gonna kill ya. He didn’t miss a thing there, that boy didn’t. I don’t think they did anything with him about it.”

This Bill Brumfield, I remembered, was Brandon’s great-great grandfather. As Bob spoke of his departed ancestor, I noticed how Brandon just sat there without taking any offense, as some might want to do. Gathering the information seemed more important than family pride — at least for the moment. Brandon asked Bob if he remembered anything about Charley and Ward Brumfield’s murder in 1926.

“What they got into was very foolish,” Bob said. “Charley would come up there — and Ward was his nephew — and they’d ride up into the head of Harts Creek and get them some whisky and they’d drink. They went up around them Adamses — they was kin to the Dingesses and Brumfields — and bought them a bottle of whisky from this guy and they got his wife to cook them a chicken dinner. She cooked them up a nice chicken dinner and, of course, they drank that liquor and was pretty dern high, I expect. They was sitting there eating and they was a damn fella… Who was that killed them? They’s so dern many of them a shooting and a banging around among each other that I couldn’t keep track of them. He was just kind of a straggler.”

Bob thought for a moment then said, “Eustace Ferguson. Now, Eustace Ferguson was a brother to Hollene’s second husband, Wesley. They had asked him to go with them and he caught an old mule or something and followed them. He was mad at them ’cause he didn’t like the Dingesses and Brumfields anyway. He followed them up there and they was eating dinner. He come in there and told them if they had anything to say they better say it ’cause he was gonna kill them. And Charley raised out of there and he said, ‘Well, by god, I’d just as soon die here as anywhere,’ and he started shooting and they just shot the devil out of each other. And he killed Charley and Ward and Charley shot him but he got somebody to get him to the doctor before the Brumfields got up there ’cause he knew them Brumfields would kill him if they got up there in time. He begged them not to report it till he had time to get to Chapmanville to get into the hand of the law. And those people wasn’t too friendly to the Brumfields and they kept it hid for about an hour or two before they reported that.”

I asked Bob if there were any dances around Harts in his younger days and he said, “Not in my time. They had a few dances ’round here and yonder but I was too young to go.”

Were there any dances at Al and Hollena Brumfield’s store?

“I don’t think so. They wasn’t the dancing type. I never was around her too much. Sometimes I’d be there and play with her grandchildren, Tom and Ed Brumfield. They were about my age.”

19 Saturday Oct 2013

Posted in Fourteen

Tags

Appalachia, Caleb Headley, Fourteen, genealogy, Gladys Kirk, history, Johnny Headley, Moses Headley, Sarah Headley, Ward Adkins, West Virginia, Will Headley, writing

On July 18, 1903, Billy and Sarah Sias, with Sarah and Moses C. Headley, sold 30 of the remaining 34 acres of Caleb Headley’s estate to Cosby (Headley) Fry. It was located just across the creek from Caleb’s old home place.

“Beginning on a beech and white oak corner to John H. Fry & the company on a point below the Hinkles branch thence,” the deed for this 30-acre tract reads, “with John H. Fry line to Albert Neace corner thence with said Neace line to S.A. Sias corner thence down the creek with the meander of said creek to the mouth of the branch opposite Sarah Headley house she now lives in thence up said branch to the mouth of the first drain on the lower side of said branch thence up said drain to the back line between the company & Caleb Headley deceased thence with said line to the beginning it being part of Caleb Headley’s deceased.”

The remaining four acres of Caleb Headley’s estate remained in tax books from 1903 until 1910, when it was dropped with the following notation: “improper by sheriff.” Oddly enough, its value had risen from $2.50 per acre to $4.00 per acre in 1905.

In 1903, the same year Sarah and Moses Headley sold the remainder of the family estate to the Frys, they bought 45 acres of land (containing the original home place) from Sarah Sias. They kept it until 1909, when they sold it to Zack Neace. In 1918, Neace sold it to Van Alford, a son-in-law to Johnny Headley.

By the early twenties, Sarah Headley still made her home with her single sons, Ballard and Moses. In 1922, Moses married Lizzie Nelson (at his residence according to records) and soon left Sulphur for good. First, he settled in Chapmanville, then South Charleston, where he died and was buried.

“Uncle Mose married Lizzie Nelson and moved to Chapmanville,” said Ward Adkins, late resident of Sulphur Springs, in a 2003 interview. “He lived in a log cabin he had built and moved in there before they even finished a floor.”

In 1924, Ballard Headley married Claire D. Clark. About that same time, Will Headley opened a store near his home at the mouth of Sulphur.

“They had a small grocery store, him and Maw, from about 1924 until about 1927 just over from where the church house is now,” said Adkins.

In July of 1929, Johnny Headley’s wife, Emaline, died of dysentery flux and he remarried early the following year to widow named Emarine Elkins.

Throughout that time, Sarah Headley just came and went, staying with first one relative and then another.

“Ever since I can remember she would drop in and maybe stay a week with us, then she’d go somewhere else and stay,” said Adkins. “She’d go up on Harts Creek a lot of times and stay. She’d stay with Bal maybe a week and Uncle Johnny over on Steer Fork.”

“She used to come to Grandpa Johnny Headley’s and stay a few nights,” said the late Gladys Kirk, a granddaughter of Johnny Headley and a resident of West Fork. “Then she would go on back to Will’s. I was small at that time, maybe eight or nine years old. She wouldn’t do anything. She’d sit around. She was too feeble to cook or anything. She held on to a big red handkerchief she packed with her everywhere she went. It was folded. We never got to look in it but it looked like she had something in it. She told someone it was her burying clothes, whatever that meant. And when Grandmaw Headley would get meals ready Grandma Sarah would make the kids line up and she’d say, ‘They’s nobody going to the table to eat until they washed their hands.'”

Around 1935-36, Sarah Headley moved in with Will permanently.

“I guess she finally got too old to go from place to place,” said Adkins. “Anyhow, she come to our house and stayed there till she died. She’d got rid of her furniture by then but she had a whole set of these old big woven baskets she kept her clothes in. She was a kind person. I liked to hear her tell tales, you know. And I don’t know how many skirts she would have on at once. Six or seven — maybe more. She’d pull up that apron, run her hand down in there, get her pipe and her tobacco out. She died in 1945 when I was away fighting in World War II.”

19 Saturday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Al Brumfield, Bob Adkins, Charlie Conley, crime, Green McCoy, Henderson Dingess, history, Hollene Brumfield, Hugh Dingess, John Brumfield, Lincoln County, Milt Haley, writing

A few days later, I picked Brandon up at his apartment in Huntington and we drove to see Bob Adkins in Hamlin. We parked on the street in front of Bob’s house (just past the red light) and walked up onto the front porch where his wife, Rena, a very friendly and cordial lady, met us at the door. She welcomed us inside to the living room. We listened to Bob speak of Milt Haley’s death. It was clear that his memory had faded somewhat since my last trip to see him in 1993.

“Well, what the trouble was there, that fella Runyon, he had a saloon and a little old grab-a-nickel store right across the creek there at the mouth of Harts,” Bob said. “And Aunt Hollene and Al Brumfield, they had a big store over there on the lower side of the creek. They was competitors in a way, you know. And that fella Runyon, he wanted to get rid of them, see. He hired these two thugs to kill them. These fellas Milt Haley and Green McCoy were two characters. And a fella by the name of Runyon gave them a side of bacon and a can of lard to kill them…each.”

Bob laughed, fully aware of how it would all turn out and seemingly amused.

“They got in a big sinkhole up above the road with a high-powered gun — a .30.30 Winchester.”

According to Bob, Haley and McCoy waited in that sinkhole for Al and Hollena Brumfield to pass by.

“Ever Sunday, Aunt Hollene — she was my mother’s aunt — she’d go up to the forks of Big Hart about ten miles up there to visit her father, old Henderson Dingess. Al had a fine riding horse and he’d get on the horse and she’d ride behind him. They’d go up there on a Sunday and have dinner with her father. And they’d been up there — it was a pretty summer day — and they came along about three or four o’clock in the evening. They shot at Al’s head and that high-spirited horse jumped and that bullet missed his head and hit Hollene in the side of the jaw — knocked her teeth out. That knocked her off’n the horse. Of course, that horse sprang and run. But they had come down off’n the hill and they aimed to shoot Aunt Hollene again. And she a laying there in the road — her eyes full of blood. She couldn’t see hardly who it was. She begged them not to shoot her anymore — she told them she was dying anyway.”

So where was Al Brumfield at that time?

“Al got offa the horse down below there and come back under the creek bank and got to shooting at them see and they took off,” Bob said. “Hollene got over that. She was my mother’s aunt. I was around her home a lot. She lived in that big white house in Hart. Burned down now.”

How did they figure out who ambushed the Brumfields?

“Well, they didn’t know who it was,” Bob said. “But they noticed they weren’t around home, the Brumfields and Dingesses did. They was watching all around to see who it was. And these two guys just left their families and went into Kentucky. Just deserted their families. Then they knew who it was. After they got a hold of them, the Dingesses and the Brumfields, they told them the whole story. That was at my grandfather’s home. They took one guy out there in the yard and gagged him so he couldn’t make a noise and stuck a gun in his back and told him if he made any noise they’d shoot him. So he listened to that other fella inside the house. That other fella broke down and cried and he told them the truth about it. And they killed both of them over at Green Shoal. Took them out in the yard and shot them all to pieces. Walked off and left them. I was born and raised about three quarters of a mile below there.”

I asked Bob why the Brumfields did not avenge John Brumfield’s murder with the same ferocity. John, I knew from Brandon, was killed by Charlie Conley at a Chapmanville Fourth of July celebration in 1900.

“I don’t know,” he said. “But I’ll tell you, John Brumfield, he was mean as a snake anyway. He treated them fellers pretty rough. And they killed him up there in the head of Hart in an association ground. They just walked up to him in that association ground — a whole bunch of people there — and shot his brains out.”

An association ground?

“They had them once a year near an old schoolhouse,” Bob said. “People’d all gather in and they had a place where they traded horses. Half a mile away, an old country preacher would preach to them. It was kind of a rough place up in there at that time.”

19 Saturday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley, Music, Women's History

16 Wednesday Oct 2013

Tags

Appalachia, Cabell County, Doc Suiter, Dolph Spratt, fiddlers, Fred B. Lambert, Guyandotte River, history, John Thomas Moore, logging, Lucian Mitchell, Paris Brumfield, Thomas Dunn English, timbering, W.M. Carter, writing

The weather was also a problem for loggers, who often plied the river in freezing temperatures.

“I was on the water that cold Saturday, about 1900,” W.M. Carter of Ferrellsburg told Fred B. Lambert, regional historian. “People froze to death, finger and toe nails froze off, but we went on.”

Some loggers built fires on their rafts to battle the cold.

“I have had fires on a raft in winter by throwing sand between close logs,” Mitchell said.

For warmth and a little light-hearted comfort, the loggers drank whiskey along the way. A resident of the Salt Rock area told Lambert about hearing “a hundred men passing his home, one night, about 1896” who “were gloriously drunk and filled the air with such cursing and yelling as one hears not more than once in a lifetime.” Johnson’s Representative Men of Cabell County, West Virginia (1929) said “they were often so boisterous that children playing along the banks ran away in fright as they heard these raftsmen sweeping by, yelling and swearing lustily. Yet, they were only a lot of mountaineers taking their trips as high adventure.”

In addition to their whiskey, loggers also used music to alleviate the hardship of their trip. They always had one or two fiddlers with them who sometimes played on the ride downriver. Thomas Dunn English’s poem “Rafting on the Guyandot” hinted at that part of the journey with the line: “Where’s the fiddle? Boys, be gay!” The fiddles were brought out again after dark, when loggers were camped at various points on the riverbank, in the yard of inns or at houses along their route where people made a business of caring for them. Raftsmen spent their evening eating packed lunches (or fresh, home-cooked meals if they were lucky), drinking, dancing, then sleeping it all off in preparation for the next day.

I could just picture Milt Haley playing the fiddle under the stars and lifting the spirits of burly men who were gathered around their campfires.

“If no bad luck overtook them, they could make the whole journey to Guyandotte in one or two days,” according to The Llorrac.

At that location, their timber was caught in a boom, then examined by measuring crews, who paid them based on the quality and usability (per cubic foot) of each log.

“Here they were delivered to sawmills or run into the Ohio where they were gathered into ‘fleets’ containing many rafts,” Lambert wrote. “They were sold to lumber dealers in Cincinnati, Louisville, Jeffersonville, Indiana, or other cities, and floated down the river.”

Having rid themselves of their timber, the loggers found vacant hotel rooms or boarding houses in the town of Guyandotte and set about the business of “having a good time.” Locals had no choice but to surrender to them and prepare for the worst.

Ferrell’s Centennial Program put it thusly: “When the timbermen had anchored their rafts, the good people of the town anchored themselves at home.”

The whole scene was as exciting and dangerous as any thing in the Wild West. There were a lot of horrible atrocities, like when John T. Moore was burned to death after some loggers renting the upstairs of his large house caught the whole place on fire.

“I’ve seen some fancy fights in Huntington among the raftsmen,” Lucian Mitchell said. “Policemen usually didn’t interfere. Dolph Spratt of Mingo County or Paris Brumfield hit Doc Suiter. He toned down after that.”

After several days of hell-raising, loggers bought a final half-gallon of the best whiskey and made plans to return home. Most made their way back upriver on borrowed or rented horses and mules — or less dramatically by walking. (To get to Harts by foot was a six or seven day trip.)

“They often went in crowds of twenty-five to fifty,” Lambert wrote.

It was rare for them to return home sober, and when they did, it often warranted special attention by local newspapers.

“We note with satisfaction that the raftsmen all returned home safely,” one reported, “and we are pleased to say that the absence of drunkedness among them on this trip was indeed gratifying.”

15 Tuesday Oct 2013

Posted in Fourteen

Tags

Appalachia, Ballard Headley, crime, Dave Headley, Dave Merrill, Fourteen Mile Creek, genealogy, Harry Tracy, history, Sarah Headley, Will Headley, writing, Zachary Neace

During the 1890s, Sarah Headley remained on Sulphur Spring Fork, although tax records and oral tradition do not indicate the exact location of her dwelling house. In that span of time, according to tax records, her property valuations increased significantly. In 1891, a 50-acre tract climbed from $100 to $125, a 45-acre tract went from $69 to $90 and a 26-acre tract jumped from $39 to $156.

In 1892, Margaret Headley, Sarah’s youngest daughter, married Zachary T. Neace, a well-to-do timberman on the creek. In subsequent years, they lived in Virginia, the place of Neace’s origin, or on Fourteen Mile Creek.

In 1893, Sarah Headley — perhaps taking advantage of a rising evaluation on her property — sold a 45-acre tract of land worth $90 to an unknown party, leaving her with only 76 acres of the 455 acres she had owned just after her husband’s death in 1882.

A few years later, Dave Headley, Sarah’s 23-year-old son, was accidentally shot and killed.

“Dave was aiming to sell this guy a gun and this guy was looking at it and it went off and shot Dave in the head,” said Ward Adkins, a step-great-grandson to Sarah Headley, in a 2003 interview. “When Will and Uncle Johnny first heard about it they aimed to kill that guy, then they found out it was an accident.”

In the late 1890s, Will Headley, who had left Sulphur around the time of the disastrous house fire and spent time with his uncle Burl Farley on Harts Creek, moved back to Fourteen after marrying Caroline Lucas, a daughter of William R. and Emily (Fry) Lucas. He and his wife settled near the mouth of Sulphur where he continued to assist his mother and family.

During that time, Sarah Headley was still somewhere on Sulphur. In 1897, she sold 42 acres — including 16 acres of the old homeplace — to Sarah A. (Nelson) Sias, whose husband Billy had bought 174 acres from Headley in 1884. Three years later, she was listed there in the Lincoln County Census as “Sarah A. Hedley,” age 51, with sons Ballard, age 20, and Moses, age 15.

Just after the turn of the century, Ballard Headley joined the army and left Sulphur Spring for a few years.

“Uncle Bal joined the army and they sent him West,” said Adkins. “I think he was in one or two Indian skirmishes and he deserted and joined a gang with Harry Tracy and Dave Merrill, two famous outlaws. I was reading a book about Harry Tracy. I asked him, ‘Did you ever hear of Harry Tracy when you was out West?’ He said, ‘Son, I rode with him.’ He said, ‘We was horse thieves. We’d steal horses from one state and take them into another state and sell them and then steal some there and take them somewhere else and sell them.’ He wasn’t afraid of nothing. He told me himself he held up a passenger train one time, too.”

Harry Tracy, the outlaw supposedly befriended by Headley, was born in Wisconsin in 1874. At a young age, he drifted west to Wyoming where he hooked up with a gang of cattle rustlers who worked with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In 1897 he was arrested in Salt Lake City but escaped and went to Colorado where he joined the Hole-In-The-Wall gang. He was arrested there and sent to jail in Aspen, Colorado, but escaped a short time later after nearly killing a guard with a lead pipe. He next went to Oregon, where he met gambler Dave Merrill in a saloon. The pair committed their first crime together in January of 1899. They were soon arrested and Tracy and sent to Oregon State Penitentiary. In December of 1899, he and Merrill were transported to Olympia, Washington to face charges, where they again escaped. They were both free for New Year’s in 1900, but were captured again in Portland a short time later. On the morning of June 9, 1902, Tracy and Merrill broke out of prison, leaving behind dead and wounded guards. On June 28, Tracy killed Merrill in a duel near Napavine, Washington. Thereafter, he hijacked a boat, which dropped him off near Seattle. He slipped through the city and crossed the Snoqualmie Pass, before he killed himself after a shoot out with a small posse in Creston, Washington.

“Uncle Bal was mean,” Adkins said. “He wasn’t out West long but when he came back here he told my grandpa Neace, who ran the post office, ‘If any mail comes here for George Golden, it will be for me. You hold it for me.’ Sure enough, there was. And by the time the government tracked him down for desertion he was blind as a bat. Some people said he put his eyes out to keep from going back in the army but he didn’t. He said he’d caught this disease and it got in his eyebrows and he put red persipity in there to kill it and got out and got to working and went to sweating and it got in his eyes and put his eyes out.”

“Now Bal was awful intelligent,” Adkins continued. “He’d come up and he’d have me to read the Bible to him. He belonged to the church. And he knew the Bible all ready, I don’t know why he’d want me to read it. But I’d try to skip on him. Maybe I’d just down here eight or ten verses. He’d say, ‘Hold on, back up there.’ Then he’d start quoting it off to me.”

15 Tuesday Oct 2013

Tags

Appalachia, Carol Caraco, Fred B. Lambert, history, Logan County, logging, Lucian Mitchell, Milt Haley, rafting, timbering, West Virginia, writing

Milt Haley, by all accounts, made his living as a timber man. He was probably lured “over the mountain” from the Tug River section by the timber industry that evolved in the Guyandotte Valley following the Civil War. It certainly played a role in his death. Really, for all practical purposes, logging was imbedded in the life fabric of every person living around Harts Creek in 1889…including little Ed Haley, who grew up in the era when timbering and steamboats gave way to coal and the railroad.

“Almost from the very beginning of history in this region, logs have been rafted on the Guyandotte and floated to Cincinnati and even to more distant markets,” according to Fred B. Lambert’s The Llorrac (1926). “In autumn, men with saws and axes went into the woods and cut down the trees. At first, the trees were so plentiful that they could be cut and rolled directly into the stream. In some cases, the bark was peeled from the logs and they were allowed to slide down the mountain side. But gradually the timber along the shore became scarce, and timbermen were compelled to go farther and farther into the hills or up the creeks, until now most of the virgin timber has been cut, and they are beginning on the second growth and, in some places, even on the third.”

The logging season began with the construction of logging camps “during the late winter and early spring months before the spring rains began to swell the creeks and rivers,” according to River Cities Monthly.

The men who came into these camps for work “were men in every sense of the word, and their beards of many days growth betrayed the fact that razors as well as some one to use them were quite scarce…,” Lambert wrote. They worked silently but would “yell like wild men” if something “unusual” happened. They were “master hands at swearing” and often fought amongst themselves, be it for sport or in fits of rage. Because of their wild nature, a foreman was often hired to regulate their activity. At night, they slept on bundles in crude log cabins. If the camp was large enough, a mess hall was constructed and a cook was hired to serve them bacon, beans, bread, coffee “or whatever may be brought into the camp from the surrounding country.”

According to Carol Caraco’s The Big Sandy (1979), loggers marked their timber by branding it with their initials. After branding their logs, they got them out of the hollow and to the river, usually by use of horse or oxen and cant hooks. Another often-used method involved splash dams. “When thousands of logs accumulated behind the timber and stone splash dam, a key wedge would be removed and the timber spewed forth,” Caraco wrote. As the logs made their way down the creek, many were jammed or land-locked along the bank.

At the mouth of creeks and rivers were “taker-ups” and booms. “The taker-ups were free-lance agents who caught and held unrafted logs until the owners appeared,” according to Caraco. “When their charge for this service proved excessive, the legislature standardized fees. Other times loose logs were stopped by a boom, a dam of huge poplar logs reinforced by a giant chain stretched across the stream.”

This boom concept, as well as questions about branding, were apparently at the heart of the 1889 troubles.

According to The Llorrac, “After the logs were all in the river, they were arranged into a raft and held in position by hickory pins driven through the small tiepoles. Later they were made more secure by the use of iron ‘chain dogs.’ Three men were required to build a raft; one to sight or place the logs, one to carry poles, and one to drive pins or chaindogs. They received a dollar a day each and it took about a day. The rafting was done in the fall and winter so as to be ready to go out on the first ‘log-tide’ of spring or early summer. An experienced raftsman always knew when it was safe to go. And well he did, for below him were the treacherous falls and shoals and eddies ready, without a moment’s notice, to hurl him to a terrible death. When the day came for the trip and the oarsmen decided that the river was at safe ‘log tide,’ the great ropes were loosened, the men took their places, the raft slowly moved into the current, and the wild ride was on.”

Based on Lambert’s notes, rafts moved at speeds of eight or nine miles per hour in convoys of fifty or more.

“There was an oarsmen at the bow’ and another behind, directing, with their strokes, every movement of the raft,” he wrote. “No one who has ever been near the river when rafts were passing, can fail to have heard the strange calls of the raftsmen to each other as they rounded the bends of the river or passed through dangerous chutes or rapids.”

“The man on the bow didn’t have to know much,” according to Lucian Mitchell, an old rafter who spoke with Lambert. “The man at the stern knew where to go, where the shoals were, and how to work up to the point on a hard bend and knew the Jordan sands at the mouth of Bear Creek. Sometimes a raft would cork the river by bowing and swing around in such a position as to get both ends afoul. If another raft came down it was rulable to hit this raft in the middle and cut it in two pieces.”

“This was a thrilling time,” The Llorrac claimed. “The front oar was often broken, leaving the raft unmanageable and, in the language of the raftsmen, it sometimes ‘swarped’ or turned completely around and even went to pieces. Let no one minimize the danger. If by accident, a man lost his balance and fell into the water, he was generally carried at once by the eddies to the bottom of the river; or, he drifted under the raft and was seen no more until his body was found, drifting far below, after many days or even months. In case they escaped these dangers they were still subject to sunken logs or great stones.”

Lucian Mitchell of Logan County downplayed the drowning aspect, saying, “Not many drowned. Most could swim.”

Writings from my travels and experiences. High and fine literature is wine, and mine is only water; but everybody likes water. Mark Twain

This site is dedicated to the collection, preservation, and promotion of history and culture in Appalachia.

Genealogy and History in North Carolina and Beyond

A site about one of the most beautiful, interesting, tallented, outrageous and colorful personalities of the 20th Century