West Virginia Banjo Player 5

29 Friday Nov 2013

29 Friday Nov 2013

27 Wednesday Nov 2013

Posted in Big Harts Creek, Chapmanville, Ed Haley, Harts, Music

Tags

Al Brumfield, Anthony Adams, Ashland, Bill's Branch, blind, Brandon Kirk, Cain Adkins, Cecil Brumfield, Chapmanville, Charley Davis, Cow Shed Inn, Crawley Creek, Dave Brumfield, Dick Thompson, Earl Brumfield, Ed Haley, Ellum's Inn, fiddler, fiddling, Fisher B. Adkins, Green McCoy, Harts Creek, Henderson Dingess, Hoover Fork, Hugh Dingess, John Brumfield, Kentucky, Lincoln County, Lincoln County Schools, Logan, Logan County, Milt Haley, music, Piney Fork, Smokehouse Fork, Trace Fork, Trace Mountain, West Fork, West Virginia, writing

A few days after visiting Earl Brumfield, Brandon dropped in on his good friends, Charley Davis and Dave Brumfield. Davis was an 88-year-old cousin to Bob and Bill Adkins. Brumfield was Davis’ son-in-law and neighbor. They lived just up Harts Creek near the high school and were familiar with Ed Haley and the story of his father, Milt. Charley said he once saw Ed in a fiddlers’ contest at the old Chapmanville High School around 1931-32. There were two other fiddlers in the contest — young men who were strangers to the area — but Ed easily won first place (a twenty-dollar gold piece). He was accompanied by his wife and a son, and there was a large crowd on hand.

Dave said Ed was mean as hell and laughed, as if it was just expected in those days. He said Ed spent most of his time drinking and playing music in all of the local dives. Sometimes, he would stop in and stay with his father, Cecil Brumfield, who lived in and later just down the road from the old Henderson Dingess place on Smoke House Fork. Dave remembered Ed playing at the Cow Shed Inn on Crawley Mountain, at Dick Thompson’s tavern on main Harts Creek and at Ellum’s Inn near Chapmanville. Supposedly, Ed wore a man out one time at a tavern on Trace Mountain.

Dave said he grew up hearing stories about Ed Haley from his mother’s people, the Adamses. Ed’s blindness was a source of fascination for locals. One time, he was sitting around with some cousins on Trace who were testing his ability to identify trees by their smell. They would put first one and then another type of limb under his nose. Dave said Ed identified oak and walnut. Then, one of his cousins stuck the hind-end of an old cat up under his nose. Ed smiled and said it was pussy willow.

Dave said he last saw Ed around 1945-46 when he came in to see his father, Cecil Brumfield. Ed had gotten drunk and broken his fiddle. Cecil loaned him his fiddle, which Ed never returned. Brumfield later learned that he had pawned it off in Logan for a few dollars to buy a train ticket to Ashland. Cecil bought his fiddle back from the shop and kept it for years.

Dave’s stories about Milt Haley were similar to what his Aunt Roxie Mullins had told me in 1991. Milt supposedly caused Ed’s blindness after getting angry and sticking him head-first into frozen water. Not long afterwards he and Green McCoy were hired by the Adamses to kill Al Brumfield over a timber dispute. After the assassination failed, the Brumfields captured Milt and Green in Kentucky. Charley said the two men were from Kentucky — “that’s why they went back there” to hide from the law after the botched ambush.

The vigilantes who captured Milt and Green planned to bring them back to Harts Creek by way of Trace Fork. But John Brumfield — Al’s brother and Dave’s grandfather — met them in the head of the branch and warned them to take another route because there was a rival mob waiting for them near the mouth of the hollow. Dave said it was later learned that Ben and Anthony Adams — two brothers who had ill feelings toward Al Brumfield — organized this mob.

The Brumfield gang, Dave and Charley agreed, quickly decided to avoid the Haley-McCoy rescue party. They crossed a mountain and came down Hoover Fork onto main Harts Creek, then went a short distance down the creek and turned up Buck Fork where they crossed the mountain to Henderson Dingess’ home on Smoke House Fork. From there, they went up Bill’s Branch, down Piney and over to Green Shoal, where Milt played “Brownlow’s Dream” — a tune Dave said (mistakenly) was the same as “Hell Up Coal Hollow”. Soon after, a mob beat Milt and Green to death and left them in the yard where chickens “picked at their brains.” After Milt and Green’s murder, Charley said locals were afraid to “give them land for their burial” because the Brumfields warned folks to leave their bodies alone.

Brandon asked about Cain Adkins, the father-in-law of Green McCoy. Charley said he had heard old-timers refer to the old “Cain Adkins place” on West Fork. In Charley’s time, it was known as the Fisher B. Adkins place. Fisher was a son-in-law to Hugh Dingess and one-time superintendent of Lincoln County Schools.

In the years following the Haley-McCoy murder, the Brumfields continued to rely on vigilante justice. Charley said they attempted to round up the Conleys after their murder of John Brumfield in 1900, but were unsuccessful.

19 Tuesday Nov 2013

Posted in Ferrellsburg, Music

25 Friday Oct 2013

Posted in Big Ugly Creek, Ferrellsburg, Music

Tags

Archibald Harrison, Arena Ferrell, Big Ugly Creek, C&O Railroad, Cleme Harrison, Daniel Fry, Don McCann, Ferrellsburg, genealogy, George W. Ferrell, Guy Harrison, Guyandotte River, Guyandotte Valley, Harold Ray Smith, Harts Creek District, history, Keenan Ferrell, Laurel Hill District, Lincoln County, Logan County, Martha E. Harrison, Martha Harrison, music, Nancy Fry, Nine Mile Creek, Phernatt's Creek, Tazewell County, Virginia, writing

Around the turn of the century, in the years just prior to the arrival of the C&O Railroad in the Guyandotte Valley, George W. Ferrell, a musician in present-day Ferrellsburg, busily wrote songs about local personalities and events. Today, Ferrell’s solitary grave is marked with an ornate tombstone that sits at the edge of what was, until recent years, a garden.

George W. Ferrell was born on October 10, 1874 to Archibald B. and Martha E. (Fry) Harrison. Archibald was the son of Guy P. and Cleme (Harmon) Harrison of Tazewell County, Virginia. Mary was the daughter of Daniel H. and Nancy P. (Bailey) Fry of Logan County. Ferrell’s birthplace is not known because, soon after his parents married in 1865, they left the area, settling at first in Kentucky and then elsewhere.

In 1878, George, then four years old, returned to Lincoln County with his parents. In 1880, his family lived near the mouth of Big Ugly Creek or at the “Bend,” just across the Guyandotte River. Shortly thereafter, they made their home at Phernatt’s Creek, further downriver in Laurel Hill District.

By 1889, Ferrell’s father — who was perhaps recently divorced from his mother — had sold all of the family property in Harts Creek District and at Phernatt’s Creek and relocated to Nine Mile Creek.

Details concerning Ferrell’s early life remain elusive. It is not known who influenced him musically or when he even started writing or playing music. There is no indication of his father or mother being musicians but his mother’s first husband, Jupiter Fry, was a well-known fiddler on Big Ugly. Some of his first songs may have been inspired by his father’s stories of the Civil War.

At some point in his young life, and for reasons unknown, Ferrell was adopted by Keenan and Arena Ferrell, a childless couple at Ferrellsburg in Lincoln County.

“I heard he was just a big old boy when the Ferrells took him in,” said Don McCann, current owner of the property surrounding Ferrell’s grave. “They didn’t have any children of their own.”

In the 1900 Lincoln County Census, Ferrell was listed as their 25-year-old adopted son. More than likely, he was assisting the Ferrells in the operation of their store and business interests.

It is easy to see how Ferrell would have become acquainted with his future foster parents.

“His father worked a lot of timber around Big Ugly or Green Shoal,” said Harold R. Smith, Lincoln County genealogist and historian. “And that would have put him in close contact with the Ferrells at Ferrellsburg.”

But why was he not living with his mother (wherever she was), who died in 1901, or his maternal grandmother, who was alive on Big Ugly? And what was his connection to the Ferrells?

19 Saturday Oct 2013

Posted in Ed Haley, Music, Women's History

27 Friday Sep 2013

Posted in African American History, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Annie Adkins, Anse Blake, Appalachia, Ben France, Bob Claypool, Bob Glenn, Burgess Stewart, Cain Adkins, Champ Adkins, Charley Robinson, Dave Glenn, Ed Haley, fiddling, Frank Jefferson, Fred B. Lambert, George Stephens, Gilbert Smith, Harkins Fry, Hezekiah Adkins, history, Isom Johnson, Jimmie Rodgers, Kish Adkins George Crockett, Leander Fry, Lish Adkins, Lucian W. Osbourne, music, Percival Drown, Spicie McCoy, Staunton Ross

In a separate interview, one Mr. Miller told Fred B. Lambert, “Leander Fry used to come down from Lincoln on timber to play the fiddle. He was a great fiddler. Jack McComas was an old fiddler, as was also his brother. Mose Thornburg said that a man who wouldn’t fight to the music made by the musicians of the musters had no fight in him. Wm. Collins was a fifer. John Reece was a tenor drummer, Clarke Thurston a base drummer. On muster days, whiskey, ginger ales, cider, &c were plentiful. Hogs were fattened on the way East. That wore the valley out. Dishes were plain. Cups instead of glass. They were cheaper. No washboards. Lye soap. Used a board to beat clothes with. Later, washboards were made of soft wood and sold for 5 cents each. Old fiddlers: George Stephens and Wiley, — Joplin, Guyandotte (?). In later days Morris Wentz and Ben France.”

Amaziah Ross told Lambert about some of the other fiddlers.

“Old Charley Robison came from Alabama. Brought ‘Birdie.’ He was a colored man and a good fiddler. Bob Glenn lived up Ohio River about Mason Co., played at Guyandotte when I was a boy. A first class fiddler. His bro. Dave Glenn also was a good one. Jimmie Rodgers lived at Guyandotte. He was a bro. to Bascom Rogers who kept saloon at Guyandotte — The Logan Saloon when I was a boy.”

Ross gave Lambert the names of many old fiddle tunes, which I of course noted being an avid fan and collector of such things:

Shelvin’ Rock played by Ben France

Natchez Under the Hill

Seven Mile Winder

Money Muss

Devil’s Dream

Mississippi Sawyer

Sixteen Days in Georgia

Little Sallie Waters

Marching Through Georgia

Whitefield, Georgia

Annie Adkins — By herself a fiddler when my father was a boy.

Ocean Wave

Over the Way

Grasshopper

Cabin Creek

Fisher’s Hornpipe

Sailor’s Hornpipe

Ladies’ Hornpipe

Gerang Hornpipe

Forked Deer

Third Day of July

Butterfly

Birdie

Lop Eared Mule

Billy in the Lowground

Wild Horse

Old Bill Keenan

Round Town Girls

SourwoodMountain

Old Joe Clark

Greasy String

Cross Keys

Bet My Money on Bobtail Horse

Blue Ridge Mountain Home

Someone told Lambert about the dances held after corn-shuckings.

“After a few weeks, it was ready to shuck. It was an opportunity for young and old to gather and spend a day at work in the name of play. Of course, the women and girls prepared the noon meal and sometimes even the supper. When night came on, the labors of the day were followed by a dance, which of all pioneer amusements was king. Shooting matches with rifles, wrestling matches, foot races, fist fights between neighborhood bullies, or to settle old scores. It was not uncommon for contestants to engage in ‘gouging’, as a natural sequence of a first fight. Weapons were banned, but many a man lost an eye by having it gouged out.”

Another person said, “Dances were very common at weddings, and on many other occasions.” Some of the tunes played were:

The Devil’s Dream

Old Zip Cook

Billie in the Low Ground

Virginia Reel

“I had a Dog And His Name was Rover,

When he Had Fleas, He had ‘Em All Over”

Irish Washerwoman

Mississippi Sawyer

Myron Drumond gave these tunes to Lambert: “Sugar in the Gourd”, “Chicken Reel”, “Fisher’s Hornpipe”, “Cincinnati Hornpipe” (the latter two tunes for “Jig dancing”) and “Irish Washerwoman”.

These tunes and fiddlers came from “a Barboursville man:”

Tunes

Turkey In the Straw

Sourwood Mountain

“Hage ’em Along.”

The Lost Indian

Pharoah’s Dream

Hell up the Coal Hollow

The Devil’s Dream

Shady Grove

Arkansas Traveler

Little Bunch o’ Blues

New River Train

I Love Some Body

Hard Up

Fiddlers

Morris Wentz

Ben France

Percival Drown

Bob Claypool—Lincoln Co.

Staunton Ross—near Salt Rock

Burgess (“Coon”) Stewart — Lincoln Co. Buffalo Cr. Extra Good

Frank Jefferson — Nine Mile

Anse Blake — Nine Mile

A lot of Lambert’s research, particularly in regard to old-time music trailed off around the time of the War Between the States. He only mentioned Ed Haley twice — once in relation to Milt Haley and once in a list with Ben France, Blind Lish Adkins, Hezekiah Adkins of Wayne County, “Fiddler Cain” Adkins (a son of Jake Adkins), Gilbert Smith and Isom Johnson. His last letter on fiddling was from an uninterested Lucian W. Osbourne of East Lynn, Wayne County, who wrote in March of 1951: “Complying with your request, I send the names of a few old fiddlers, as follows: Champ Adkins, Kish Adkins, Ben Frances, George Crockett. All dead. For information about others write Mrs. Spicy Fry, Stiltner, and Harkins Fry, Kenova. Here are some of the old tunes: ‘Sourwood Mountain,’ ‘The Lone Prairie,’ ‘Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,’ ‘Nelly Gray,’ &c. I know but little about the fiddling, as I am a Sunday School man, and interested in better things. I think it is better to say after one when he is dead that he is a Christian than to say he was a fiddler or baseball fan.”

24 Tuesday Sep 2013

24 Tuesday Sep 2013

Tags

Don Lambert, fiddling, Henry Pauley, Henry Peyton, history, Irvin Lucas, Jack McComas, Jim Franklin, Johnny Dalton, Leander Fry, Lincoln County, Tom Cooper, West Virginia

In 1925, likely stirred by Pomp Wentz’s comment, Fred B. Lambert interviewed Blind Bill Peyton of One Mile Creek, near West Hamlin in Lincoln County. Initially, Mr. Peyton spoke a great deal of his father, Henry Peyton, a fiddler, farmer, and timber man in the Guyandotte Valley.

“My father was among the first settlers on this creek,” Peyton said. “He settled about a mile and a half up from the river and raised all his 13 children in the same house. He followed farming mostly, and timbered some and sold some timber. Raised all kinds of stock — sheep, cows, hogs, horses — one dog at a time. Raised chickens, turkeys, guineas, pea fowls, geese, ducks, etc. My father was a good canoe maker. He made them out of poplar trees by digging out and shaping them, at $12 to $25, according to size. I often went to Logan for rafts. Henry Peyton, my father, Walter Lewis, Bob Lewis, and Dick Cremeans took a big barge of lumber to Cincinnati. Lumber was sawed early by a whip saw.”

“My father was a fiddler — played many a night,” Peyton said. “Young folks had a good many parties. Had all night dances. Uncle John Spears was the oldest fiddler I knew. He lived on Nine Mile Creek of Lincoln up on creek toward head. He was a good one. Some of the old-time tunes were: Maysville, Rebel Raid, Dalton Raid, Sourwood Mountain, Getting Off the Raft, Shelvin’ Rock, Dover, The Coquette, Leather Breeches Full of Stitches, Betsy Walker, Frosty Morning, Rollin’ Down the Sheets, The Grand Spy, Daniel Boone, Capt. Johnson, Cincinnati Belle, Rose in the Mountain, Rocky Mountain, The Blue Rooster, The Morning Star, The Butterfly, Tinpot Alley, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, Butcher’s Row, The Brush Creek, Peach Tree, Waynesburg, The Basket, Nancy Rowland, The Arkansaw Traveler, and Cumberland Gap.”

Peyton spoke of other Lincoln County fiddlers, some of whom lived in the Harts area during Milt Haley’s time.

“Johnny Dalton, a blacksmith, came from East Virginia, settled at Falls, was a fiddler. Did your work and then played you a tune. Went to Mud River and died. Jack McComas of 6 mi. and Jim Franklin from Upper Two Mile were also fiddlers. Tom Cooper lived on Mud River, in Lincoln, above Hamlin. Morris Wentz and Ben France, who lived in Cabell, often came to Lincoln. Tom Peyton, my brother, Mig Sturgeon, Don Lambert, Irvin Lucas, and Leander Fry were fiddlers. The latter was a good one. Henry Pauley came from Boone County; settled on Parsoner Creek, and removed to near Four Mile of Guyan. He was well liked. Mr. Billy McKendree told of Dangerfield Bryant being a good fiddler and teacher of singing and instrumental music. A shoemaker by trade. He was lame. A good man and perfect gentleman.”

23 Monday Sep 2013

Posted in Music

Tags

Appalachia, Cabell County, fiddler, fiddling, Fred B. Lambert, Guyandotte River, history, J.T. "Pomp" Wentz, music, photos, steamboats, West Virginia

J.T. “Pomp” Wentz, riverboat captain in the Guyandotte Valley. From the Fred B. Lambert Papers, Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Marshall University, Huntington, WV.

23 Monday Sep 2013

Posted in African American History, Civil War, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Babe McCallister, banjo, Ben France, Billy Walker, Charley Dodd, civil war, fiddling, Henry France, Henry Peyton, history, J.T. "Pomp" Wentz, Jack McComas, Lincoln County, Morris Wentz, West Virginia, William S. Rogers

By the time of the Civil War, Benjamin France of Cabell County was the chief fiddler in the lower Guyandotte Valley. One person interviewed by Fred B. Lambert referred to him as “the best of all” in a list of fiddlers that included even Ed Haley. Of course, I was immediately interested in him.

According to Lambert’s notes, France was born in 1844. He “learned on a gourd fiddle, and was able to play when he entered the army. He served as a Rebel soldier, throughout the Civil War, entering the army, at the age of 17 years. He was noted as one of the best fiddlers of his time. He won two or three times, in contests, but his medals do not show when, nor whether they were first rank. Henry France, his nephew, says he could play all the old fiddle tunes, and could play all night without repeating the same tunes even once.”

France was a resident of Long Branch, near the Lincoln County line and died in 1918.

“From Cabell County, the principal fiddlers were Morris Wentz, Ben France, William S. Rogers and Charley Dodd,” according to J.T. “Pomp” Wentz, a riverboat captain who spoke with Lambert. “Banjoes were not used so much, in those days, but later Rev. Billy Walker and others used to play them very well. As a fiddler, Ben France played with the most ease of any man I ever saw. Morris Wentz played with some difficulty compared with Mr. France, but he could play almost anything. Morris Wentz used to play: ‘The Cold Frosty Morning’, ‘Going Back to Dixie’, ‘The Arkansas Traveler’, ‘Bonaparte’s Retreat’ (this pleased Billy Bramblett, the Frenchman), ‘Ducks in the Pond’, ‘The Puncheon Floor’, ‘Hop Light Ladies’, ‘The Boatsman’, ‘The Cackling Hen’, ‘Sourwood Mountain’, ‘Soldiers Joy’, ‘Little Birdie’, ‘Old Dan Tucker’, ‘Granny Will Your Dog Bite?’, ‘Liza Jane’, ‘The Shelvin’ Rock’, ‘Knock Kneed Nannie’, ‘Chippy, Get Your Hair Cut’, ‘The Rebel Raid’, ‘Turkey in the Straw’, ‘Sugar In the Gourd’, ‘Ginny, the Gal With the Blue Dress On’, ‘Old Joe Clark’, ‘Birdie’, ‘Old Napper’, ‘The Forked Duck’. After dancing the ‘set’ down, they would close with the ‘winder’.”

Apparently, the popular tunes of the day were “Forked Deer” and “The Peach Tree”.

“Babe McCallister, ‘a darkey’ owned by a farmer named McCallister from upper Mud River, was a master of ‘Forked Deer’,” one fiddler raved. “He ‘played the fiddle with the ‘free arm movement,’ the wrist joint only working, the elbow joint still, while the wrist joint was in active movement. To hear the coon on ‘Forked Deer’, his favorite tune, and call the cotillion figure was a great treat. Could I have inherited such talent with my fondness of and for the violin, it would have been dead easy that I should tour the universe and earn a million playing only ‘Forked Deer’ and ‘Peach Tree’.”

Further up the Guyandotte River from the Cabell County towns, in present-day Lincoln County, were fiddlers of lesser note.

“Some of the best fiddlers I ever knew in Lincoln County, were Henry Peyton, father of ‘Blind’ Bill Peyton, and Jack McComas, both of whom played before the Civil War,” said Pomp Wentz.

21 Saturday Sep 2013

Posted in African American History, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

fiddling, Fred B. Lambert, George Stephens, Gus Wolcott, history, Ike Handley, Jim Peatt, Jim Wilcot, Morton Milstead, music, Percival S. Drown, Sam Peatt, slavery

“There were other fiddlers of less note than those I have named,” Percival Drown continued. “Jim Peatt was a fiddler of fair attainments only as to the number of tunes. I only remember that he played ‘Pigeon on the Gate’, ‘Indian Eat the Woodcock’ (with words), and ‘Old Dan Tucker’ with words and chorous… Ike Handley and Jim Wilcot, who lived below Guyan seven or eight miles, were of the class with Jim Peatt, as I now regard them and recall their fiddling.”

Around 1846, a “dark-skinned” fiddler named Joplin with a “French-Italian look about him” appeared briefly in Cabell County. He was “an educated fiddler and dancing master.”

“It was charming to me, at least, to listen to Joplin’s refined music and I scarcely let the opportunity pass and not hear him,” Drown wrote.

While a master of the violin in the classical sense, Joplin didn’t impress many locals.

“The average native of Cabell County at the period of which I am writing,” one citizen said, “would be far more entertained listening to George Stephen’s ‘Possum Creek’ or ‘Soap Suds over the Fence’, or ‘Peach Tree’ as he played it by ear, than Joplin’s classics rendered from book Clythe Masters.”

These fiddlers made a great impression on young Percival Drown, who took up the fiddle himself as a teenager.

“As brief as I can make it, I will give an account of my own career as a fiddler, which is of little merit, yet would appear to be in order to detail here with other reminiscent memories,” he wrote.

Early in the 40s my father said to me: “Perl would you like to learn to play the fiddle?” I was in my thirteenth year, I think. “Yes sir, I certainly would,” was about my reply — I think my exact words. He went on at some length in extolling the virtues of the violin — how a fiddler could elevate himself socially, and even become a great and popular personage. I have no idea he had ever listened to Joplin or Turner at that time, and certainly not an Ole Bull, or other high class performers. “Bonaparte’s Retreat” and “Money Musk”, also the “Irish Washerwoman,” were his special tunes to listen to. He then said: “Take this $3.00 and get Vere or Gus Wolcott (who kept the wharfboat at Logan) to send to Cincinnati and get the best instrument the $3.00 will buy, and you can begin and try and learn”. I took the money. Wolcott sent and got the instrument, and I was not long “to try and learn to play on it.” The employment of a teacher was out of the question — not to be thought of. We lived far in the back country, too far from where an instructor of the violin ever came. I could never have paid the tuition of an instructor could one have been engaged, but the husband of a negro woman and two children my father had bought at a public sale of the property of Joe Gardner, dec’d at Guyan, was a fiddler. My father hired the husband [named Sam] every winter to work on the farm. Sam became my teacher. I watched his fingers as he played “Old Grimes”, and by timing the fingers and getting the tune effectively fixed in my mind, it was not long until I could actually play “Old Grimes” myself, by which time I could also “tune up” the instrument. The worst was over.

[I learned] by listening to Geo. Stephens, and every other fiddler that came along the road, closely watching Sam’s fingers and hearing him play every rainy day that we wouldn’t work on the farm (and every night, rain or dry). In four to six months I could play any slow tune and the “Peach Tree” for a dance. For a cotillion I could play one tune, “Rose in the Mountain”. On an occasion, I think it was near 1846, a popular blacksmith and farmer named Stonebreaker who lived out on Beech Fork wanted to give the young people a party. So, he gathered his corn crop, hauled it into the barn, and appointed a day for the husking. “Corn shucking” it was called. The day for the corn shucking was Saturday. George Stephens was sought for, but was away and could not be got in time. Walcott lived twenty miles away, and was not known much anyway. Milstead lived in Ohio, fifteen miles or more. Joplin lived in Gallipolis, thirty miles up the Ohio, too. Hence, he was not available. I had no reputation as a fiddler, and Sam could not leave home — his wife was expecting to be sick of another kid — when it seemed that no fiddler of any known qualification could be engaged. A messenger was sent for me to ascertain if I would come, the time being short. I readily assented. Nothing said about the fiddler’s fee for the service. On the day set I done up the fiddle in my overcoat, and strapping it behind my saddle, mounted “Dave” a very comely animal and away to Stonebreaker’s. Afternoon I went nine or ten miles. Made the trip in good shape, arriving as big as life, fiddle and all. The husking of the corn concluded, the next order of business was to dance. The figures chiefly danced were “Virginia Reel”, “French Four”, and “Dan Tucker”. I could only play the “Peach Tree” in fairly good shape for dancing; and the “Peach Tree” it was for all night, except for supper. We adjourned for about an hour. Then on with the dance for the balance of the night. For this service I received all that was collected, 75 cents, fifteen times five cents in 5 cent pieces… but like George Stephens I felt that I, too, was a lilter. That was my very first playing for the dance. That was fully 68 years ago.

In 1854 I obtained another and superior instrument that, figuring some time ago how many miles I had carried that violin, it amounted to some 38,000 miles.

20 Friday Sep 2013

Tags

Anthony Riggs, Barboursville, fiddler, fiddling, Fred B. Lambert, George Stephens, Guyandotte River, history, Morton Milstead, music, Percival S. Drown, Samp Johnson, writing

The next morning, I went to see the Lambert Collection at the Morrow Library in Huntington, West Virginia. According to information at the library, the late Fred B. Lambert (1873-1967), a schoolteacher and administrator, had spent “at least sixty years of his life collecting information about West Virginia history” into a 500-notebook collection, mostly focusing on Cabell, Lincoln, Wayne, and Logan Counties. His notes on fiddling and old-time music were incredibly detailed. In some cases, he documented the first time a tune arrived in the Guyandotte Valley. Incredibly, none of his work was published outside of The Llorrac, an old high school yearbook from the 1920s.

As I flipped through his notebooks, it was difficult to keep my focus — there were stories about murders, genealogy, and life on the river. I took great interest in the stories about early fiddlers in the Guyan Valley. It helped put Ed — at least his early years — into a sort of regional context, the culmination of years of musical evolution. Any one of the mid-nineteenth century Guyan fiddlers may have actually known Ed Haley or, more likely, his father Milt.

In the 1830s and 1840s, according to Lambert’s research, George Stephens was a dominant fiddler in the Cabell County towns situated at or near the mouth of the Guyandotte River.

“George Stephens was a fiddler of wider reputation than most of those old time artists of the ‘fiddle and the bow,'” wrote one Percival S. Drown in a 1914 letter. “In his repertoire was ‘Bonaparte’s Retreat from Moscow,’ ‘Bonaparte Crossing the Rhine,’ ‘Cold, Frosty Morning,’ ‘Puncheon Floor,’ ‘Possum Creek,’ ‘Pop Goes the Weasel,’ ‘Pretty Betty Martin,’ ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginia,’ ‘Hail Columbia,’ and ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ He had another tune and words ‘Big John, Little John, Big John Bailey.’ The tune Stephens seemed to throw himself away most on was the ‘Peach Tree.’ The meter and time governing this tune permitted its use and adaptation for dance music, and applying a long drawn bow with correct harmony and concord of sound, he carried the listener away in dreamy thought and recollection.

“When about midnight after the day of the ‘quilting,’ ‘Corn Husking,’ and ‘Log Rolling,’ when the ‘dance was on,’ Stephens, well-liquored up on Dexter Rectified, would have his face turned over his right shoulder apparently as much asleep as awake, but never missing a note of the ‘Peach Tree’, while the dancers would be ‘hoeing down’ for dear life. All at once he would order ‘Promenade to Seats’, cease playing, adjust himself in his seat and exclaim with energy ‘if I aint a lilter damme.’ Seemingly he was suddenly inspired with an exalter opinion of his greatness as a fiddler. As much as to say at the same time ‘and don’t you forget it.’ Then he might resen his bow and break out with a few stanzas of ‘Puncheon Floor’ or a tune he called ‘Soap Suds Over the Fence,’ to be followed by a slow tune so everyone could march to the supper table in the kitchen, across the yard (It was a common thing in those dear old times, for the kitchen to be detached from the ‘big house’).”

Samp Johnson was another top local fiddler, according to Percival Drown.

“‘Samp’ Johnson was the first fiddler I heard play ‘Arkansas Traveler’. One of his favorite places to play was at McKendree’s Tavern in Barboursville [on Main Street]. His favorite for playing was during Court days, when fiddler’s drinks were full and plentiful. The sun [was] full at 2 o’clock that day. Court day. The Town was full of visitors, chiefly ‘hayseed’, most of whom were fully equipped for home when they could tear themselves away from ‘Samp’ Johnson’s music. I well remember the day. McKendree’s second story porch was crowded with the audience. Roll Bias, who was a character in his day, lived far up Guyan River. He usually had business ‘at Court’. He was prosperous, in a way. I think he paid for all the drinks flowing from the attraction furnished by Johnson’s music in the street. While endowed with good common sense he could neither write his own or any other name. Poor ‘Samp’ Johnson came to his death at the Falls of Guyan when driving logs at high tide of the river, date not far from the time (1852) of my leaving the State.”

Another great fiddler in that era was Anthony Riggs.

“Anthony Riggs’ favorite tune that I more distinctly remember than others he played was called ‘Annie Hays,'” Drown wrote. “It was that fiddler’s favorite tune and one to suit the step and time for reels, and other ‘figures’ so called. Like all fiddlers of his class, he played ‘Nachez Under the Hill’, now known as ‘Turkey in the Straw.'”

Morton Milstead of Ohio “would come over to Cabell, stay around a few days, in the early 30s, I heard it said, and played the fiddle for drinks, mostly,” Drown wrote. “Milstead was rated as a high-class musician, as I recollect the talk of him. Never heard Milstead play but once, and I well remember now after a lapse of 65 or 70 years that his performance was much below that of George Stephens, Anthony Riggs, or ‘Samp’ Johnson, from my viewpoint at least.”

30 Friday Aug 2013

Posted in Calhoun County, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Akron, Appalachia, Calhoun County, culture, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, history, Kerry Blech, life, music, Ohio, photos, Rector Hicks, U.S. South, West Virginia

24 Saturday Aug 2013

Posted in John Hartford, Music

Tags

Appalachia, banjo, bluegrass, culture, history, John Hartford, life, Museum of Appalachia, music, Norris, photos, Tennessee

11 Tuesday Jun 2013

Tags

Ashland, banjo, Bernard Postalwait, Calhoun County, Clay County, Clay Court House, Doc White, Ed Haley, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Ivydale, Kim Johnson, Laury Hicks, Lawrence Haley, Minnora, music, Riley Puckett, Roane County, Steve Haley, West Virginia, Wilson Douglas, writing

In mid-summer of 1994, I was back in Ashland visiting Lawrence Haley. Lawrence, I noticed right away, was indeed in poor health. His overall appearance wasn’t good; actually, he seemed convinced that he probably wouldn’t get any better. Pat was ever so cheerful, saying that he would be back to his old self soon enough. Lawrence’s son Steve had driven in from Hendersonville, Tennessee, to serve as his replacement on any “Ed Haley trips.”

Early the next morning, Steve Haley and I left Ashland to see Wilson Douglas, the old-time fiddler who remembered Ed Haley in Calhoun County, West Virginia. We drove east on I-64 past Charleston, West Virginia, where we exited off onto a winding, two-lane road leading to Clendenin, an old oil town on the Elk River. We soon turned onto a little gravel driveway and cruised up a hill to Wilson’s nice two-story home. We parked and walked up to the porch where we met Wilson and his banjo-picker, Kim Johnson. Inside, he told me more about seeing Ed at Laury Hicks’ home. He was a great storyteller, so we naturally hung onto his every word.

“Laury Hicks got in touch with Ed Haley,” he began. “So, in them days, you come to Charleston by train and from Charleston to Clay Court House by train. All right, when you got to Clay Court House, you caught the B&O train on up to Otter, which is Ivydale. Well, the word would come out and they’d be somebody there in an old car or something to pick him up and take him about fifteen, 20 miles over to Hicks’ in Calhoun County. Well, the word’d get around, you know, and my god, it was just like a carnival a coming to town. And my dad had an old ’29 model A Ford pick-up truck. Well, gas was 11 cents a gallon. So, what we’d do, we’d take our pennies or whatever we had, we’d get us that old truck up — had a big cattle rack on it — and everybody’d load in that thing. Say, ‘Well, Ed Haley’s over at Laury Hicks’. Let’s go, boys!’ Everybody would grab their loose pennies, which were very few, and we’d get over there.

“Well, it’d be probably dark, or a little before, when he would start fiddling — about maybe eight o’clock — and last until three in the morning. And he would never repeat hisself unless somebody asked him. We just sat and never opened our mouth and he’d scare [them other fiddlers]. I’d sit there till I’d get so danged sleepy, I’d think I couldn’t make it. He’d start another tune and it’d just bring me up out of there. And that Chenneth on that banjo. And then they was a fellow, he lived down the road about seven or eight miles, a fellow by the name of Bernard Postalwait. And this man was a “second Riley Puckett” on the guitar. Well, Ed’d send for him. By god, they’d never miss a note. Ed had a little old tin cup sitting there. Everybody’d put some money in it, you know. And they was some rich feller, but I can’t think of that danged guy’s name, he liked fiddle music. He’s the only man in Roane County that had any money. Well, he’d give a few one-dollar bills, you know, and he’d mention a tune. Well, if he give him a dollar, he’d play it for fifteen minutes. Well, by the time the night ended, he’d have five or six dollars, which was equivalent to fifty now. Well the next night, we’d go over — all of us’d work that day. Next night, the same thing: we’d be right back over.”

Wilson said Ed would get drunk with Bernard Postalwait and “disappear” to some rough establishments. Bernard was with Ed when he played his fiddle at Laury Hicks’ grave.

Ed also ran around with a casual fiddler named Benjamin F. “Doc” White (1885-1973) of Ivydale. Doc was a banjo-picker, veteran of the Indian Wars, schoolteacher, midwife, doctor, photographer, local judge and dentist (he even pulled his own teeth). He took Ed to “court days” and other events where he could make money.

“I was around old Doc a lot,” Wilson said. “God, he was a clown. He had kids all over West Virginia. He couldn’t fiddle much but he tried.”

Doc asked Ed one night, “Ed, how do you play them tunes without changing keys?” and Ed said, “Well Doc, I change them with my fingers!”

Wilson said Ed wasn’t being sarcastic.

It seemed like Wilson knew a lot of stories about Ed’s “running around days” with guys like Postalwait and White — which would have been great to hear to get a better understanding of him — but he refused to be very specific. He did tell one story:

They went over to a place called Minnora. That’s over where Laury Hicks lived. Doc White and Ed. Somebody else was with them, I think that Bernard Postalwait. They went down there to a Moose Lodge or something and they had a little fiddle contest or something. Well, now, Ed said, “I ain’t gonna play in this contest.” Said, “I’d ruther be a judge.” Now Old Doc White, you know, he had quite a bit of money. I don’t know, they’s four or five fiddlers that played. Old Doc played a tune, you know. They said, “What do you think, Ed?” Well, Ed said, “Boys, I hate to say it. By God, old Doc’s gotcha all mastered.” Course Ed was wanting a drink of liquor, you know. After it was over, by God, they got drunk, all of them. Doc couldn’t play much, but Ed said, “Well, that old Doc’s got you boys bested.”

02 Sunday Jun 2013

Posted in John Hartford, Music

Tags

Appalachia, banjo, bluegrass, culture, fiddle, fiddler, history, John Hartford, Museum of Appalachia, music, Norris, photos, Tennessee

23 Thursday May 2013

Tags

Appalachia, banjo, culture, history, life, photos, U.S. South

19 Sunday May 2013

Posted in Music

Tags

Appalachia, banjo, Cush Adams, Harts Creek, history, Logan County, music, photos, U.S. South, West Virginia

Baisden family members, Trace Fork of Big Harts Creek, Logan County, West Virginia, 1940s.

18 Saturday May 2013

Posted in Big Harts Creek, Music

07 Tuesday May 2013

Posted in Music

Tags

Appalachia, Boyd County, Ed Morrison, fiddle, fiddler, genealogy, history, Kentucky, life, music, photos, U.S. South

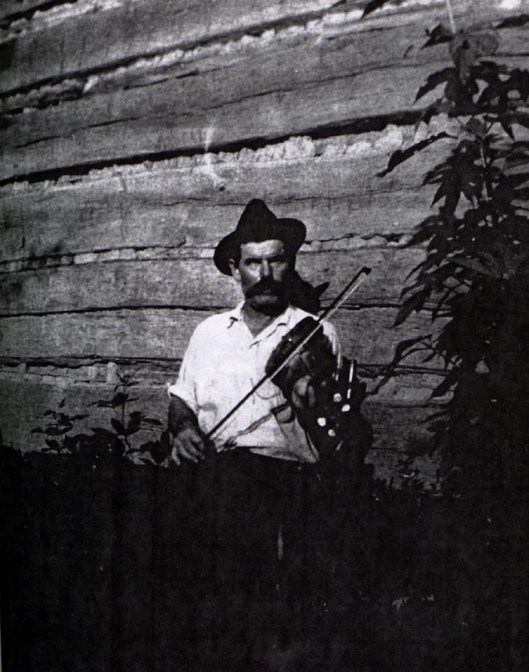

Ed Morrison, a Boyd County, Kentucky, fiddler, c.1925. Another photo of Mr. Morrison can be found here: http://digital.library.louisville.edu/cdm/ref/collection/jthom/id/1102

Writings from my travels and experiences. High and fine literature is wine, and mine is only water; but everybody likes water. Mark Twain

This site is dedicated to the collection, preservation, and promotion of history and culture in Appalachia.

Genealogy and History in North Carolina and Beyond

A site about one of the most beautiful, interesting, tallented, outrageous and colorful personalities of the 20th Century