Tags

Appalachia, Brandon Kirk, genealogy, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Kentucky, Perry Cline, photos, Pike County, Pikeville

Perry Cline grave, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Perry Cline grave, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

30 Monday Apr 2018

Posted in Big Sandy Valley, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Pikeville

Tags

Appalachia, Brandon Kirk, genealogy, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Kentucky, Perry Cline, photos, Pike County, Pikeville

Perry Cline grave, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Perry Cline grave, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

29 Sunday Apr 2018

Tags

39th Kentucky Infantry, African-Americans, Ann Dils, Appalachia, Basil Hatfield, cemeteries, civil war, Dils Cemetery, genealogy, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, John Dils Jr., Kentucky, Martha Hatfield, Martha McCoy, National Register off Historic Places, photos, Pike County, Pikeville, Randolph McCoy, Roseanna McCoy, Sam McCoy, Sarah McCoy, slavery, Union Army

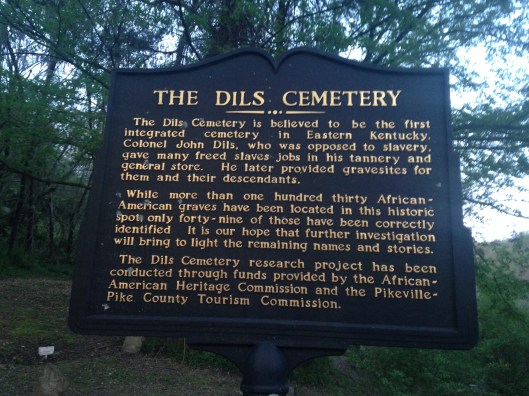

The Dils Cemetery Sign, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

McCoy Family wreath, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

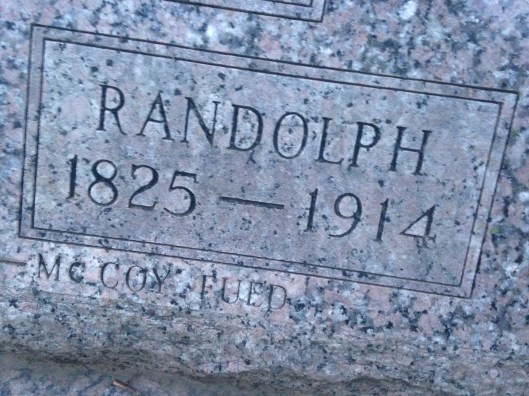

Randolph and Sarah McCoy graves, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Randolph McCoy grave, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Roseanna McCoy grave, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Col. John Dils grave, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

History Marker, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Basil Hatfield grave sign, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Basil Hatfield grave, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

Sam and Martha McCoy grave, Dils Cemetery, Pikeville, KY. 27 April 2018.

28 Tuesday Nov 2017

Posted in Culture of Honor, Gilbert, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Matewan, Pikeville

Tags

Alifair McCoy, Appalachia, Beech Creek, Calvin McCoy, Chafinsville, crime, Dan Cunningham, Devil Anse Hatfield, Dollie Hatfield, feud, feuds, Floyd County, Frank Phillips, genealogy, George Hatfield, Gilbert Creek, Greek Milstead, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Henry Clay Ragland, history, Huntington Advertiser, Johnse Hatfield, Johnson Hatfield, Kentucky, Logan County, Logan County Banner, Matewan, Mingo County, murder, Nancy Hatfield, Norfolk and Western Railroad, Oakland Hotel, Pikeville, Portsmouth Blade, Prestonsburg, Southern West Virginian, T.C. Whited, Thomas H. Harvey, true crime, Vanceville, West Virginia

From the Logan County Banner of Logan, WV, and the Huntington Advertiser of Huntington, WV, come the following items relating to Johnson Hatfield:

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 20 February 1890. Also appeared on 13 March 1890.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 30 July 1891.

***

We are glad to see that Johnson Hatfield, who has been confined to his room for the last ___ weeks, is able to be on the street again.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 2 March 1893.

***

There was an unfortunate difficulty at Matewan on Sunday last in which Mr. Johnson Hatfield was severely wounded through the hand. His son had become involved with an officer which drew his father into the trouble.

Source: Southern West Virginian via the Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 1 January 1896.

***

Johnson Hatfield, accompanied by his daughter, Miss Dollie, left on Monday last for a visit to friends and relatives in Mingo county.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 23 January 1897.

***

Johnson Hatfield and daughter, Miss Dollie, have returned from a visit to friends on Sandy.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 6 February 1897.

***

Johnson Hatfield, the genial proprietor of the Oakland Hotel, is visiting friends at Pikeville, Kentucky.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 28 August 1897.

***

Johnson Hatfield has returned from a visit to Pikeville, Ky.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 9 October 1897.

***

Johnson Hatfield is at Williamson this week.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 23 October 1897.

***

The many friends of Mrs. Johnson Hatfield will regret to learn of her serious illness. She has a very bad attack of rheumatism.

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 13 November 1897.

***

Johnson Hatfield and wife, of Mingo, passed through here [Chafinsville] last Sunday en route for Vanceville, where they will make their future home.

Source: Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 21 April 1898.

***

HATFIELD KIDNAPPED.

TAKEN TO KENTUCKY ON A SERIOUS CHARGE–NOW IN JAIL.

Johnson Hatfield was arrested yesterday and taken to Pikesville, Kentucky, and lodged in jail on a charge of being an accomplice in the murder of Alifair McCoy on New Years night about nine years ago. This murder was committed during the feud of the Hatfields and McCoys.

Source: Huntington (WV) Advertiser, 20 July 1898.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 21 July 1898.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 11 August 1898.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 20 October 1898.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 19 January 1899.

***

Huntington (WV) Advertiser, 21 January 1899.

***

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 12 April 1900.

NOTE: Not all of these stories may pertain to the Johnson “Johnse” Hatfield of Hatfield-McCoy Feud fame. For instance, items relating to the Oakland Hotel and a daughter named Dollie relate to a Johnson Hatfield (born 1837), son of George and Nancy (Whitt) Hatfield.

04 Tuesday Jul 2017

Tags

Appalachia, Big Sandy River, Floyd County, Hindman, Inez, Johnson County, Kentucky, Knott County, Letcher County, Levisa Fork, map, Martin County, Paintsville, Pike County, Pikeville, Prestonsburg, Russell Fork, Tug Fork, West Virginia, Whitesburg

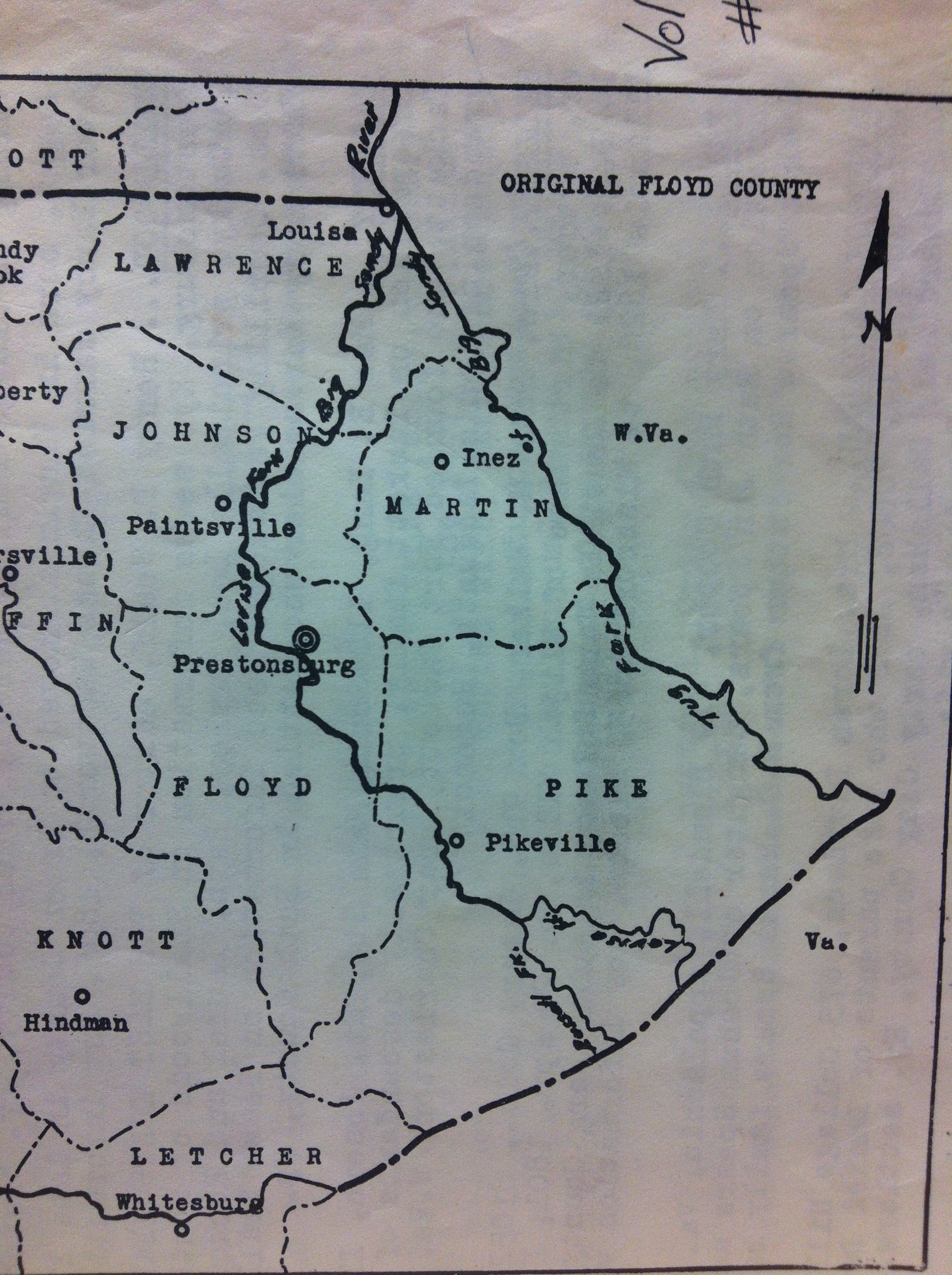

Kentucky Counties in the Big Sandy Valley.

Posted by Brandon Ray Kirk | Filed under Big Sandy Valley

09 Sunday Aug 2015

Posted in Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Lincoln County Feud

09 Sunday Aug 2015

Posted in Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Lincoln County Feud, Pikeville

Tags

Brandon Kirk, culture, Diggers, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Jenny Wiley Theatre, Kentucky, life, photos, Pike County Tourism, Pikeville, Tony Tackett, tourism

Here I am earlier today with Tony Tackett, Pike County (KY) Tourism Director, at Jenny Wiley Theatre in Pikeville, KY. Tony and his associates are unsurpassed in what they do. Many thanks to Tony and Pike County Tourism for inviting me to the Diggers premiere. It was a great time.

29 Sunday Sep 2013

Posted in Big Sandy Valley, Pikeville, Women's History

Tags

Appalachia, Big Sandy River, culture, history, Kentucky, life, photos, Pikeville, steamboat, U.S. South

“Waiting on a boat,” Pikeville, Kentucky, 1901

01 Saturday Dec 2012

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Appalachia, Ashland, Beckley, Bluefield, Chillicothe, Ed Haley, Ella Haley, Farmers, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Gallipolis, Gene Goforth, Hazard, history, Jenkins, Jess Adams, John Hartford, Kentucky, Lawrence Haley, Lexington, Missouri, Morehead, music, Nila Adams, Ohio, Pat Haley, Pikeville, Portsmouth, Pound, Princeton, Shannon County, U.S. South, Virginia, West Virginia, Winchester, writers, writing

Ed Haley spent his young bachelor days just “running around all over,” Lawrence said. He didn’t know any specifics about that time in his life but I could fill in the blanks based on memories of myself at that age. When I was growing up in Missouri, Gene Goforth, the great Shannon County fiddler took me into some of the darkest dives I could ever imagine — real “skull orchards.” Those places were filled with hot-tempered, burly men who were mean enough to fight or kill anyone. Even though Gene and I felt safe around them because we played their type of music, there was always an unpredictable danger in the air. I bet Ed’s music at that time in his life was as exciting as anything I would’ve ever wanted to hear, but to stay in some of those old taverns to hear it would’ve been like being in a cave full of rattlesnakes.

I asked Lawrence if he had any idea about how far Ed traveled with his music and he said, “I don’t know where he went when he was single, running the country. The way people talked, he started out about the time he married my mother. Hell, he was going twenty years before that. When he married my mother was more or less his settling down time. Well, I know he’s been all the way south through Beckley and Princeton and Bluefield, West Virginia and all the way down into Pikeville, Kentucky and over into Pound, Virginia. I guess he’s been as far as Hazard and Jenkins, Kentucky and all those little towns. County seats mostly is where he played.”

Lawrence didn’t think Ed made it as far west as Lexington, Kentucky. “They say that he never was down through the Bluegrass, but I’m pretty sure he’s been as far west into Kentucky as Winchester,” he said. “And I know he’s been to Morehead and Farmers; that’s a little town just outside of Morehead, Kentucky. He’s been to Chillicothe and Portsmouth, Gallipolis — up in Ohio that a way. Now, I don’t think he ever made it into the Carolinas or Johnson City, Tennessee but if he did it was before my time.”

Lawrence said his parents supported the family by playing music on the streets, but would play just about anywhere money could be made. “Pop used to go down to Portsmouth to a steel mill. It’s closed down now. It was a pretty good sized mill. They made everything from steel plate down to wire nails and fencing and everything else in there. It was Detroit Steel or one of those. He used to go down there, and he’d go to the railroad YMCA, too, because there was all the time train men coming and going on the N&W train line. A lot of train crews’d come in there and stay all night and Pop and Mom used to go in there and play right in the YMCA building. They used to do it down here at the Russell Y.”

Lawrence told me more about seeing Ed and Ella play for dances. “I’ve walked Mom and Pop to Morehead down the C&O Railroad tracks to Farmers — that’s six or seven miles — to play at a home. They’d take any rugs and furniture out of a room and pack them in another room and then dance. It might have been seven to nine o’clock sets, but it seemed to me like they lasted all night. I’ve seen Pop sit one set right after another without really stopping. When he’d play a piece of music, he’d play it as long as the caller wanted to call. Pop’d play ten minutes on a piece of music if that’s what was requested. Them was awful long sets. I’d get up and we’d start home at daybreak.”

I asked how Ed was paid for a dance and he said, “It would be more or less passing the hat or somebody coming up and wanting a certain piece of music played in a set or something. I don’t think they ever contracted a certain monetary fee for anything. They just took it as it came.”

Lawrence obviously preferred to think of Ed and Ella playing at dances instead of on the sidewalks, probably because street musicians are often regarded as being little more than talented bums. It was surely more romantic to think of them at county fairs, courthouses or little country houses. No doubt, he thought his father was above the street scene and likely had strong memories of long hot or cold days spent on sidewalks with passersby throwing out nickels and occasional slurs.

Pat gave me a little insight into that facet of Ed’s life story when she asked Lawrence if he’d told me about his “winter coat.” Lawrence said no because I wanted to know about Pop — not him — but she said, “Oh, I thought that was cute. He was a little boy and he was with his mama and they were in Cincinnati. It was very, very cold and he didn’t have a coat. And they were standing — you know his mama was playing — and his mother had told him he would get his winter coat for Christmas and he said, ‘Santa Claus better hurry up, Mama, ’cause I won’t be here.’ His mother went that very day and bought him that winter coat so he got his coat from Santa Claus a little bit early.”

Those were clearly memories that Lawrence didn’t care to re-hash.

“Sometimes it was good, sometimes it was lean,” he said. “Apparently, Mom and Pop was making enough. They always kept some kind of roof over our heads. We didn’t have anything fancy. Mom swept her own floors a lot of times, and she swept barefooted, and that’s the way she knew her floor was clean. She felt with her toes and her feet.”

Pat said, “My mother-in-law was very, very particular. She couldn’t stand to feel the least little thing on her — it bothered her. And if she sat down at your table — even though somebody would say, ‘These are very clean people’ — she would put her hand in the cup or the glass and run her hands over the plate. And I’ve heard people tell that they had the cleanest clothes in the area because she scrubbed them on a board and she would scrub twice as hard and twice as long to be sure those clothes were clean.”

On occasion, according to Pat, Ella even hired out neighbors to work for her. “Aunt Nila Adams worked some for your Mom,” she said to Lawrence. “She did a lot of the big cleaning.” She looked at me, “And his mother paid them well,” seemingly in an effort to compensate for the “winter coat” story. “She paid better than the average.”

Lawrence said, “Well, people like Nila Adams and Jess Adams — he was a hard-working man. He just was uneducated and that’s all he ever knew was hard work. And a lot of times that ditch-digging and hard work wasn’t around, so I guess Mom helped Nila Adams. When she’d come clean house for Mom she was helping Nila Adams keep her household together, too, in a way.”

One thing was to be understood: Ed Haley and his wife were not bums on the street begging for money. They were professional musicians who earned a decent living and who raised their children as well as any one else in the neighborhood.

27 Tuesday Nov 2012

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Annadeene Fraley, Appalachia, Ashland, Ballad Makin' in the Mountains of Kentucky, Bert Hatfield, Bill Day, Birdie, Black Mountain Rag, Bloody Ground, Bonaparte's Retreat, books, Canada, Catlettsburg, David Haley, Dick Fraley, Doc Chapman, Dry and Dusty, Ed Haley, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Gallagher's Drug Store, Grey Eagle, history, Horse Branch, J P Fraley, Jean Thomas, Jilson Setters, John F. Day, John Hartford, Kentucky, Lawrence Haley, Maysville, music, New Money, Paul David Smith, Pikeville, Snake Chapman, The Singin' Fiddler of Lost Hope Hollow, The Wheel, Wee House in the Wood, White Rose Waltz, writers, writing

As soon as my schedule cleared, I loaded my car and traveled north on I-65 out of Nashville toward the home of J.P. and Annadeene Fraley in Carter County, Kentucky. I took the Bluegrass Parkway northeast to Lexington, where I boarded I-64 and drove eastward past Winchester, Mt. Sterling and Owingsville. In a short time, I was in “Ed Haley country,” passing by Morehead — birthplace of Mrs. Ed Haley — and through the northern end of the Daniel Boone National Forest. A little later, I took the Grayson exit, where I found J.P. and Annadeene at their beautiful log home in a small settlement called Denton.

In the initial small talk, J.P. told about seeing Ed Haley play on the streets of Ashland. He specifically remembered him playing at Gallagher’s Drug Store where he sat cross-legged “like an Indian” with his back against the wall “right by the doors where you go in.” Ed kept a hat out for money and knew people by the sound of their voices. In the cold months, he played inside for square dances, Kiwanis Club events, and at local beer joints like “The Wheel.” J.P. said, “Now business people treated him good but the general public, they didn’t know what they was doing.”

At that point, we got our instruments out and squared up to play some tunes. As J.P. worked through his repertoire — “Birdie” (Haley’s version), “New Money”, “White Rose Waltz” — he sang little ditties and gave some of the history behind his tunes. He played a great tune called “Maysville” and said, “Daddy played it. What it was, they wasn’t no tobacco warehouses in Morehead or Flemingsburg so they had to haul their tobacco plumb into Maysville to sell it. When they was going there, they played the tune fast because they was happy. They were going to get that tobacco check, see? On the way back, they was playing it slow because they were drunk. They all had hangovers.”

J.P. also played “Grey Eagle”, “Black Mountain Blues” and “Bonaparte’s Retreat”. His treatment of this latter piece was somewhat unique — he began it with “Dry and Dusty” (“Daddy’s introduction”) — although he really bragged on Haley’s version. “If you listen to that record you got, you can hear… It’s just like cannons going off. I mean he was doing it on the fiddle. Man he had the best version of that. Ed Haley was colorful with his fiddle tunes.”

In between all of the fiddling and reminiscing, little comments spilled out about Haley. Things like, “His fingers was like a girls.” Then more fiddling.

Some time later, J.P. and I put our instruments away and sat down to dinner. Between bites, I asked him where he remembered Haley playing in Ashland.

“His range was right along 15th – 16th Street on Winchester Avenue. When you went down between Winchester and Greenup, there was shoe shops and a saloon or two and a poolroom where mostly a congregation of men were. Then over on Greenup the women’d be shopping. Sometimes he played on Front Street, but that was a wild part of town. I don’t ever remember his wife being over in there but I seen him there when the boy was picking with him. Down by the railroad over on Front Street, there used to be stores over there — and on Greenup. I mean, grocery stores, family stores. I can remember seeing him play in front of one — had to be down there. I guess around 14th Street on Greenup. I guess hunting season was going on because wild rabbits was hung up out there for sale…with the fur still on them. And stocks of bananas. Slabs of bacon, hams. I mean they wasn’t bound up to keep the flies off of them.”

After dinner, I played some of Haley’s music on cassette tapes for J.P. He casually told how people sometimes griped about Ella’s accompaniment being too loud. He also brought up how people occasionally complained when Haley played inside Ashland businesses. J.P.’s father once confronted a store owner who had asked Ed to leave his store. “Daddy told me he’d went in that hardware store, you know, to take up for Ed,” J.P. said. “The storeowner knowed Dad. He said, ‘Now Dick, you forget about it ’cause I’d ruther for him to be out there a fiddling as all them people to come in here that’s been a complaining about him.’ It wasn’t really a problem.” I said, “So he fiddled outside the hardware store all the time?” and J.P. said, “Right in that vicinity. If it was rainy or a real hot sun, you’d find him along there playing.”

Annadeene and I made plans to visit Ed’s son, Lawrence Haley, in Ashland the following day. J.P. showed me to a guest bedroom, presumably to turn in for the night, but we were soon playing music again. He cranked out “Goin’ Back to Kentucky”, then said, “I bet you money Ed Haley played that because Asa Neal did.”

The next morning, Annadeene and I hopped onto US Route 60 and made the thirty-minute drive into Ashland, the place where Ed Haley lived the last thirty years of his life. In those days, Ashland was a somewhat affluent industrial town on the Ohio River. Today, its population has dwindled to around 20,000 and its once prominent river culture seems long gone. It is best known as the hometown of country music stars, Naomi and Wynonna Judd, as well as movie actress Ashley Judd. It was clear that the place seemed to be somewhat depressed in the way most river towns are in this section of the Ohio River, outside of a budding shopping center to the northeast.

Annadeene and I drove around town for about an hour. She pointed out all the places she remembered Ed playing and told me all about his relationship with Jean Thomas, the late Ashland folklorist. I had heard of Jean Thomas and was roughly aware of the arguments for and against her work in Ashland to preserve and perpetuate mountain culture. She was the creator of the American Folksong Festival, an annual production held at the “Wee House in the Wood.” The central character in Thomas’ festival was Jilson Setters, a blind fiddler character “from Lost Hope Hollow” who Annadeene said had been inspired by Haley. She was sure of this, having served as Thomas’ personal secretary years ago.

In The Singin’ Fiddler of Lost Hope Hollow (1938), Thomas gave an account of her first encounter with ‘Jilson’ at a local courthouse: “There under the great leafy oak in the court house yard, the sun gleaming on its wet leaves, stood an old man, tall, gaunt, with a hickory basket on his arm, a long oil cloth poke clutched in his hand. It was the poke that caught my eye. Already a crowd was gathering about him. He put down the basket, then took off his dilapidated wide-brimmed felt and placed it, upturned, on the wet grass at his feet. Carefully he untied the string on the oilcloth poke and – to my surprise – took out a fiddle! In another moment, fiddle to chin, his sightless eyes raised to heaven, he swept the bow across the strings with masterly ease…and sang in a strong, a vibrant voice for one so old. While he fiddled a measure, before starting the next stanza, I fairly flew across the road. I wanted to be close at the old minstrel’s side, lest I lose a word that fell from his lips. When the song was ended I clapped loud and long, like the rest, and like them, too, tossed a coin into the old fellow’s hat.”

Annadeene said Thomas first offered Haley the opportunity to role-play Jilson Setters but he refused. He likely agreed with writer John F. Day, who offered a scathing criticism of Thomas in Bloody Ground (1941). “The trouble with most ballad-pushers, as well as of the other ‘native culturists,’ is that they’re seeking their own exultation under a guise of working for the benefit of the mountain people,” Day wrote. “One wonders as he watches the American Folksong Festival whether it’s all for the glory of God, art, and mountain balladry, or Jean Thomas, Jean Thomas and Jean Thomas. After reading one of Jean Thomas’ books I feel ill. Everything is so lovely and quaint; so damnably, sickeningly quaint. Writers like Jean Thomas would have one believe that every-other mountaineer goes around singing quaint, beautiful sixteenth-century ballads as he plunks on a dulcimer. The people of Kentucky laugh at Miss Thomas’ stuff, but the people outside the state are willing to lap it up. Now in the first place thousands of hill dwellers know no old ballads and other thousands know the old ones but prefer the newer ones. In the second place 90 per cent of the ballads and 90 per cent of the ballad singers stink. Further, the only dulcimers left in the hills are gathering dust on the walls of the settlement schools. The mountain people found out long ago there wasn’t any music in the damned things, and so they discarded them for fiddles, banjos, and guitars.”

After Haley refused to play the part of Jilson Setters, Thomas chose Blind Bill Day, a left-handed fiddler and migrant to Ashland. At some point, she took him to play his fiddle for the Queen of England. Based on Thomas’ book, Ballad Makin’ In The Mountains of Kentucky (1939), Day met his future wife “Rhuhamie” (actually named Rosie) on Horse Branch in Catlettsburg, Kentucky.

I went to Ed Haley’s the day it was bright

I met with a woman I loved at first sight.

I asked her some questions about her past life.

She told me she was single – but had been a wife.

In deep conversation I studied her mind,

She had come down to Brushy to wait on the blind;

The labor was hard and the wages was small,

I soon saw that she did not like Horse Branch at all.

Needless to say, the entire concept of Jilson Setters went a long way in destroying Thomas’ credibility as an authentic folklorist. John F. Day wrote: “The mountaineers had to be quaint. Such determination led to hoaxes like the one Jean Thomas perpetrated with ‘Jilson Setters, the Singing Fiddler of Lost Hope Hollow.’ She took this ‘typical representative of the quaint mountain folk of Kentucky’ to New York and to London and made quite a name for herself and him. But though he might have been Jilson Setters to the New Yorkers and the English he was James William Day (nicknamed ‘Blind Bill’ Day) to the people of Kentucky who knew him. There may be a ‘Lost Hope Hollow’ – they name them everything – but nobody in the Kentucky mountains ever heard of it. There was no particular harm of course in changing Bill Day’s name to Jilson Setters if the latter sounded more poetic – or something. Names are changed every day in Hollywood. The harm came in pawning off Bill, well-coached in quaintness, as a representative of the Kentucky mountain people. But the most laughable part of the whole affair was that Bill Day had lived for years in Ashland and Catlettsburg, and of all the sections of the Kentucky mountains, that in which the two cities lie is the most modern. Ashland is an industrial city of more than 30,000 population, and Catlettsburg is almost a suburb. The Big Sandy Valley was opened up years before southeastern Kentucky, and thus if one is to find any ‘quaintness’ at all he must get out of the Big Sandy country.”

Annadeene and I drove around Ashland for about an hour discussing such things before heading to nearby Catlettsburg, Kentucky on US Route 23. According to J.P. Fraley, Catlettsburg — a former boomtown for loggers who rafted timber out of the Big Sandy River at the turn of the century — served as Ed Haley’s place of residence during the twenties and early thirties. Today, its historic and interesting downtown area — featuring the Boyd County Courthouse and other buildings that attest to its short prosperous history — is almost hidden from view due to a railroad to the south and a large floodwall to the north. Its most visible section is a modern strip along US Route 23, consisting of a slow-moving four-lane road dotted with gas stations, old dwelling houses and fast-food restaurants. A sign proclaims Catlettsburg as a town of 6000 residents and maps show it situated across the Big Sandy River from the town of Kenova, West Virginia and across the Ohio River from South Point, Ohio.

After looking over the place, Annadeene and I drove back to Ashland on Winchester Avenue and turned onto 45th Street at a large, brick Presbyterian church. We drove up a narrow and curvy street until it crested at Gartrell Street, where Annadeene pointed out the home of Lawrence Haley, an unpretentious white one-and-a-half-story residence. We parked on the street and eased out of the car toward the Haley porch. As I stood there preparing to ring the doorbell, I noticed the original picture of Ed Haley featured on Parkersburg Landing hanging just inside a window on the living room wall. I had goose bumps in realizing how much this experience meant to me. After a few rings of the bell, it was clear that no one was home.

Just as we were ready to step off of the porch, a young girl with a wonderful smile came up from next door and said that her grandparents had gone over into Ohio. I realized just then that she was Ed’s great-granddaughter and was instantly as impressed as if I’d just met the daughter of the President of the United States. A stocky man with a dark mustache followed her over and introduced himself as her father, David Haley. Annadeene and I talked with him briefly, then said we’d come back some time when his parents were home. I walked out of the Haley yard wondering if the girl or her father had inherited any of Ed’s musical talent.

Later in the day, after parting ways with the Fraleys, I drove south through the Big Sandy Valley on US Route 23 to see Snake Chapman, the fiddler who remembered seeing Ed Haley so often during his youth in Pike County, Kentucky. At Pikeville, I took US Route 119 to Snake’s mountain home up Chapman Hollow near a settlement called Canada. Snake was a retired coalminer who spent most of his time caring for his sick wife. He was very mild-spoken — almost meek — and had what seemed like hundreds of cats all over his yard (even on the roof of his house). Once we began playing music, it was clear that he was a great old-time fiddler. I had a blast with his buddies, Bert Hatfield (a relative of the feuding Hatfields) and Paul David Smith.

Snake told me a little about his father, Doc Chapman. “He was an herb doctor, Dad was. Everybody knowed him by Doc Chapman. He knowed every herb that growed here in the mountains and what they was for and doctored people all around.” Doc was also a fiddler.

Snake took up his fiddle and played several more tunes, including Haley’s version of “Birdie”. Snake was a man of few words, so most of my visit consisted of playing old-time tunes. I spent the night at Bert Hatfield’s, then left eastern Kentucky on US 119 and US 25E via the Cumberland Gap.

26 Monday Nov 2012

Posted in Ashland, Big Sandy Valley, Ed Haley, Matewan, Music, Pikeville, Williamson

Tags

Appalachia, Art Stamper, Arthur Smith, Ashland, Big Sandy River, Billy Lyons, Blackberry Blossom, blind, Charles Wolfe, Clark Kessinger, Clayton McMichen, Duke Williamson, Ed Haley, fiddle, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Fox in the Mud, Frazier Moss, Fred Way, Ft. Gay, Grand Ole Opry, history, Huntington, Joe Williamson, John Hartford, Kentucky, Kermit, Kirk McGee, Levisa Fork, Louisa, Mark Howard, Matewan, Mississippi River, Molly O'Day, music, Nashville, Natchee the Indian, Ohio River, Old Sledge, Packet Directory, Paintsville, Parkersburg Landing, Pikeville, Prestonsburg, Red Apple Rag, River Steamboats and Steamboat Men, Robert Owens, Roy Acuff, Sam McGee, Skeets Williamson, Snake Chapman, square dances, St. Louis, Stacker Lee, Stackolee, steamboats, Tennessee Valley Boys, Tri-State Jamboree, Trouble Among the Yearlings, Tug Fork, West Virginia, Williamson, WSAZ

Back in Nashville, I was knee-deep in Haley’s music, devoting more time to it than I care to admit. I talked so much about it that my friends began to tease me. Mark Howard, who was producing my albums at the time, joked that if Ed’s recordings were of better quality, I might not like them so much. As my obsession with Haley’s music grew, so did my interest in his life. For a long time, my only source was the liner notes for Parkersburg Landing, which I had almost committed to memory. Then came Frazier Moss, a fiddling buddy in town, who presented me with a cassette tape of Snake Chapman, an old-time fiddler from the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy in eastern Kentucky. On the tape, Snake said he’d heard Haley play the “old original” version of “Blackberry Blossom” after he “came in on the boats” at Williamson, West Virginia.

The boats?

This was making for a great story. I was already enthralled by Haley’s fiddling…but to think of him riding on “the boats.” It was the marriage of my two loves. I immediately immersed myself in books like Captain Fred Way’s Packet Directory 1848-1983: Passenger Steamboats of the Mississippi River System Since the Advent of Photography in Mid-Continent America (1983) to see which boats ran in the Big Sandy Valley during Haley’s lifetime. Most of the boats were wooden-hulled, lightweight batwings – much smaller than the ones that plied the Mississippi River in my St. Louis youth – but they were exciting fixtures in the Big Sandy Valley culture.

“I have seen these boats coming down the river like they were shot out of a cannon, turning these bends, missing great limbs hanging over the stream from huge trees, and finally shooting out of the Big Sandy into the Ohio so fast that often they would be nearly a mile below the wharf boat before they could be stopped,” Captain Robert Owens wrote in Captain Mace’s River Steamboats and Steamboat Men (1944). “They carried full capacity loads of sorghum, chickens and eggs. These days were times of great prosperity around the mouth of Sandy. Today, great cities have sprung up on the Tug and Levisa forks. The railroad runs on both sides, and the great activity that these old-time steamboats caused has all disappeared.”

During the next few weeks, I scoured through my steamboat photograph collection and assembled pictures of Big Sandy boats, drunk with images of Haley riding on any one of them, maybe stopping to play at Louisa, Paintsville, Prestonsburg and Pikeville, Kentucky on the Levisa Fork or on the Tug Fork at Ft. Gay, Kermit, Williamson, and Matewan, West Virginia.

Finally, I resolved to call Snake Chapman and ask him about his memories. It was a nervous moment – for the first time, I was contacting someone with personal memories of Ed Haley. Snake, I soon discovered, was a little confused about exactly who I was and why I was so interested in Haley’s life and then, just like that, he began to offer his memories of Ed Haley.

“Yeah, he’s one of the influences that started me a fiddling back years ago,” Snake said, his memories slowly trickling out. “I used to go over to Molly O’Day’s home – her name was Laverne Williamson – and me and her and her two brothers, Skeets and Duke, used to play for square dances when we first started playing the fiddle. And Uncle Ed, he’d come up there to old man Joe Williamson’s home – that’s Molly’s dad – and he just played a lot for us and then us boys would play for him, me and Cecil would, and he’d show us a lot of things with the bow.”

Molly O’Day, I knew, was regarded by many as the most famous female vocalist in country music in the 1940s; she had retired at a young age in order to dedicate her life to the church.

“And he’s the one that told me all he could about old-time fiddling,” Snake continued. “He said, ‘Son, you’re gonna make a good fiddler, but it takes about ten years to do it.'”

I told Snake about reading in the Parkersburg Landing liner notes how Haley reportedly wished that “someone might pattern after” him after his death and he totally disagreed. He said, “I could have copied Uncle Ed – his type of playing – but I didn’t want to do it because he told me not to. He told me not to ever copy after anyone. Said, ‘Just play what you feel and when you get good, you’re as good as anybody else.’ That was his advice.”

I didn’t really know what to make of that comment. I mean, was Haley serious? Was he speaking from personal experience or was it just something he told to a beginning fiddler for encouragement?

After that, my conversation with Snake consisted of me asking questions – everything from how much Haley weighed to all the intricate details of his fiddling. I wondered, for instance, if Ed held the bow at the end or toward the middle, if he played with the fiddle under his chin, and if he ever tried to play words in his tunes. I wanted to know all of these things so that I could just inhabit them, not realizing that later on what were perceived as trivial details would often become major items of interest.

Snake answered my questions precisely: he said Haley held the bow “up a little in the middle, not plumb on the end” and usually played with the fiddle at his chest – “just down ordinarily.” He also said Haley “single-noted” most of his bow strokes, played frequently in cross-key, hated vibrato and used a lot of “sliding notes.” He seldom got out of first position, only occasionally “going down and getting some notes” that he wanted to “bring in the tune” and he definitely tried to play words in his music.

“The old fiddlers through the mountains here – and I guess it’s that way everywhere – they tried to make the fiddle say the words of the old tunes,” Snake said.

“Uncle Ed, he was a kind of a fast fiddler,” he went on. “Most old-time fiddlers are slow fiddlers, but he played snappy fiddling, kindly like I do. Ah, he could do anything with a fiddle, Uncle Ed could. He could play a tune and he could throw everything in the world in it if he wanted to or he could just play it out straight as it should be. If you could just hear him in person because those tapes didn’t do him justice. None of them didn’t. To me, he was one of the greatest old-time fiddlers of all time. He was telling me, when I was young, he said, ‘Well, I could make a fiddle tune any time I want to,’ but he said he just knowed so many tunes he didn’t care about making any more. He played a variety of tunes that a lot of people didn’t play, and a lot of people couldn’t play. He knew so many tunes he wouldn’t play one tune too long.”

I asked Snake about Haley’s repertoire and he said, “He played an old tune called ‘Old Sledge’ and it was one of his good ones. He played tunes like ‘Trouble Among the Yearlings’, but when he was gonna play it he called it ‘Fox in the Mud’. He made that up himself. One of the favorite tunes of mine he played was the old-time way of playing ‘Blackberry Blossom’ and he played it in G-minor. Ed could really play it good. They was somebody else that made the tune. Uncle Ed told me who it was – Garfield. He said he was a standing fiddling near a big blackberry patch and it was in bloom at the mouth of the hollow one time and this fella Garfield played this tune and he asked this fella Garfield what the name of the tune was. He said, ‘Well, I ain’t named it, yet,’ and he turned around and spit in that blackberry patch with a big bunch of ambeer and said, ‘We’ll just call it ‘Blackberry Blossom’.”

Snake laughed.

“Yeah, Uncle Ed, he had tales behind every one of them like that, but that’s where he said he got the name of it. He said he named it there…spitting in the blackberry blossom.”

Snake only remembered Haley singing “Stacker Lee”, a tune I’d heard him fiddle and sing simultaneously on Parkersburg Landing:

Oh Stacker Lee went to town with a .44 in his hand.

He looked around for old Billy Lyons. Gonna kill him if he can.

All about his John B. Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee entered a bar room, called up a glass of beer.

He looked around for old Billy Lyons, said, “What’re you a doin’ here?

This is Stacker Lee. That bad man Stacker Lee.”

Old Billy Lyons said, “Stacker Lee, please don’t take my life.

Got a half a dozen children and one sweet loving wife

Looking for my honey on the next train.”

“Well God bless your children. I will take care of your wife.

You’ve stole my John B. Stetson hat, and I’m gonna take your life.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

Old Billy Lyons said, “Mother, great God don’t weep and cry.”

Oh Billy Lyons said, “Mother, I’m bound to die.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee’s mother said, “Son, what have you done?”

“I’ve murdered a man in the first degree and Mother I’m bound to be hung.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

Oh Stacker Lee said, “Jailor, jailor, I can’t sleep.

Old Billy Lyons around my bedside does creep.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee said, “Judge, have a little pity on me.

Got one gray-haired mother dear left to weep for me.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

That judge said, “Old Stacker Lee, gonna have a little pity on you.”

I’m gonna give you twenty-five years in the penitentiary.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

It was one awful cold and rainy day

When they laid old Billy Lyons away

In Tennessee. In Tennessee.

Snake said Haley used to play on the streets of Williamson, West Virginia where he remembered him catching money in a tin cup. In earlier years, he supposedly played on the Ohio River and Big Sandy boats and probably participated in the old fiddlers’ contests, which Snake’s father said was held on boat landings. These impromptu contests were very informal and usually audience-judged, meaning whoever got the most applause was considered the winner. Sometimes, fiddlers would just play and whoever drew the biggest crowd was considered the winner.

I asked Snake if he ever heard Ed talk about Clark Kessinger and he said, “Skeets was telling me Ed didn’t like Clark at all. He said, ‘That damned old son-of-a-gun stands around and tries to pick up everything he can pick up from you.’ And he did. Clark tried to pick up everything from Uncle Ed. He was a good fiddler, too.”

Snake said Clayton McMichen (the famous Skillet Licker) was Haley’s favorite fiddler, although he said he knew just how to beat him. This made me think of the line from Parkersburg Landing, “In regard to his own fiddling, Haley was not particularly vain, although he was aware that he could put ‘slurs and insults’ into a tune in a manner that set him apart from all other fiddlers.” (I wasn’t exactly sure he meant by slurs and insults.)

Snake could tell that I was really into Haley.

“Try to come see me and we’ll make you as welcome as we possibly can,” he said. “I tell you, my wife is poorly sick, and I have a little trouble with my heart. I’m 71. Doctors don’t want me to play over two or three hours at a time, but I always like to meet other people and play with them. I wouldn’t have no way of putting you up, but you can come any time.”

Just before hanging up, I asked Snake if he had any Haley recordings. He said Skeets Williamson had given him some tapes a few years back and “was to bring more, but he died two years ago of cancer.” Haley had a son in Ashland, Kentucky, he said, who might have more recordings. “I don’t know whether he’s got any of Uncle Ed’s stuff or not. See, most of them old tapes they made, they made them on wire recordings, and I don’t know if he’s got any more of his stuff than what I’ve got or not.”

I told Snake I would drive up and see him in the spring but ended up calling him a week later to ask him if he knew any of Ed’s early influences. He said Ed never talked about those things. “No sir, he never did tell me. He never did say. Evidently, he learned from somebody, but I never did hear him say who he learned from.” I felt pretty sure that he picked up tunes from the radio. “Ed liked to listen to the radio, preferring soap operas and mystery chillers, but also in order to hear new fiddle tunes,” the Parkersburg Landing liner notes read. “A good piece would cause him to slap his leg with excitement.” I asked Snake if he remembered Haley ever listening to fiddlers on the radio and he said, “I don’t know. He must have from the way he talked, because he didn’t like Arthur Smith and he liked Clayton McMichen.”

What about pop tunes? Did he play any of those?

“He played ragtime pretty good in some tunes,” Snake said. “Really you can listen to him play and he slides a little bit of ragtime off in his old-time fiddling – and I never did hear him play a waltz in all the time I ever heard him play. He’d play slow songs that sound old lonesome sounds.”

Snake quickly got into specifics, mentioning how Haley only carried one fiddle around with him. He said, “He could tune right quick, you know. He didn’t have tuners. He just had the keys.”

Did fiddlers tune low back in those days?

“I’d say they did. They didn’t have any such thing as a pitch-pipe, so they had to tune just to whatever they liked to play.”

Haley was the exception.

“Well, it seemed like to me he tuned in standard pitch, I’m not sure. But from hearing his fiddling – like we hear on those tapes we play now – I believe he musta had a pitch-pipe at that time.”

I wondered if Haley spent a lot of time messing around with his fiddle, like adjusting the sound post, and Snake said, “No, I never did see him do that. He might have did it at home but when he was out playing he already had it set up the way he wanted to play.”

Surprisingly, Snake didn’t recall Haley playing for dances. “I don’t think he did because I never did know of him playing for a dance. He was mostly just for somebody to listen to, and what he did mostly was to make money for a living playing on the street corner. I seen him at a fiddling contest or two – that was back before I learned to play the fiddle. That’s when I heard him play ‘Trouble Among the Yearlings’. He won the fiddling contest.”

What about playing with other fiddlers?

“Well, around in this area here he was so much better than all the other fiddle players, they all just laid their fiddles down and let him play. The old fiddlers through here, they wasn’t what I’d call too good fiddlers. We had one or two in the Pikeville area over through there that played a pretty good fiddle. Art Stamper’s dad, he was a good old-time fiddler, and so was Kenny Baker’s dad.”

After hanging up with Snake, I gave a lot of thought to Haley reportedly not liking Arthur Smith. His dislike for Smith was documented on Parkersburg Landing, which stated plainly: “Another fiddler he didn’t care for was Arthur Smith. An Arthur Smith record would send him into an outrage, probably because of Smith’s notoriously uncertain sense of pitch. Cecil Williamson remembers being severely lectured for attempting to play like ‘that fellow Smith.'”

Haley probably first heard Smith over the radio on the Grand Ole Opry, where he debuted in December of 1927. Almost right away, he became a radio star, putting fiddlers all over the country under his spell. His popularity continued to skyrocket throughout the 1930s, during his collaboration with Sam and Kirk McGee. In the late thirties, Haley had a perfect chance to meet Smith, who traveled through southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky with the Tennessee Valley Boys. While unlikely, Haley may have met him at fiddling contests during the Depression. “In the thirties, Haley occasionally went to fiddle contests to earn money,” according to Parkersburg Landing. At that same time, Smith was participating in well-publicized (usually staged) contests with Clark Kessinger, Clayton McMichen and Natchee the Indian. Haley, however, tended to avoid any contest featuring Natchee the Indian, who “dressed in buckskins and kept his hair very long” and was generally a “personification of modern tendencies toward show fiddling.”

In the early 1940s, Haley had a perfect opportunity to meet Smith, who appeared regularly on WSAZ’s “Tri-State Jamboree” in Huntington, West Virginia. Huntington is located several miles up the Ohio River from Ashland, Kentucky and is West Virginia’s second largest city.

In the end, Haley’s reported low opinion of Smith’s fiddling was interesting. Arthur Smith was one of the most influential fiddlers in American history. Roy Acuff regarded him as the “king of the fiddlers,” while Dr. Wolfe referred to him as the “one figure” who “looms like a giant over Southern fiddling.” Haley even had one of his tunes – “Red Apple Rag” – in his repertoire. Maybe he got a lot of requests for Smith tunes on the street and had to learn them. Who knows how many of his tunes Haley actually played, or if his motives for playing them were genuine?

Writings from my travels and experiences. High and fine literature is wine, and mine is only water; but everybody likes water. Mark Twain

This site is dedicated to the collection, preservation, and promotion of history and culture in Appalachia.

Genealogy and History in North Carolina and Beyond

A site about one of the most beautiful, interesting, tallented, outrageous and colorful personalities of the 20th Century