Tags

Appalachia, Ellis Ball Park, fiddlers, fiddling, Grand Ole Opry, history, Kirk McGee, Logan, Logan Banner, Logan County, music, Sam McGee, Sarie and Sallie, West Virginia

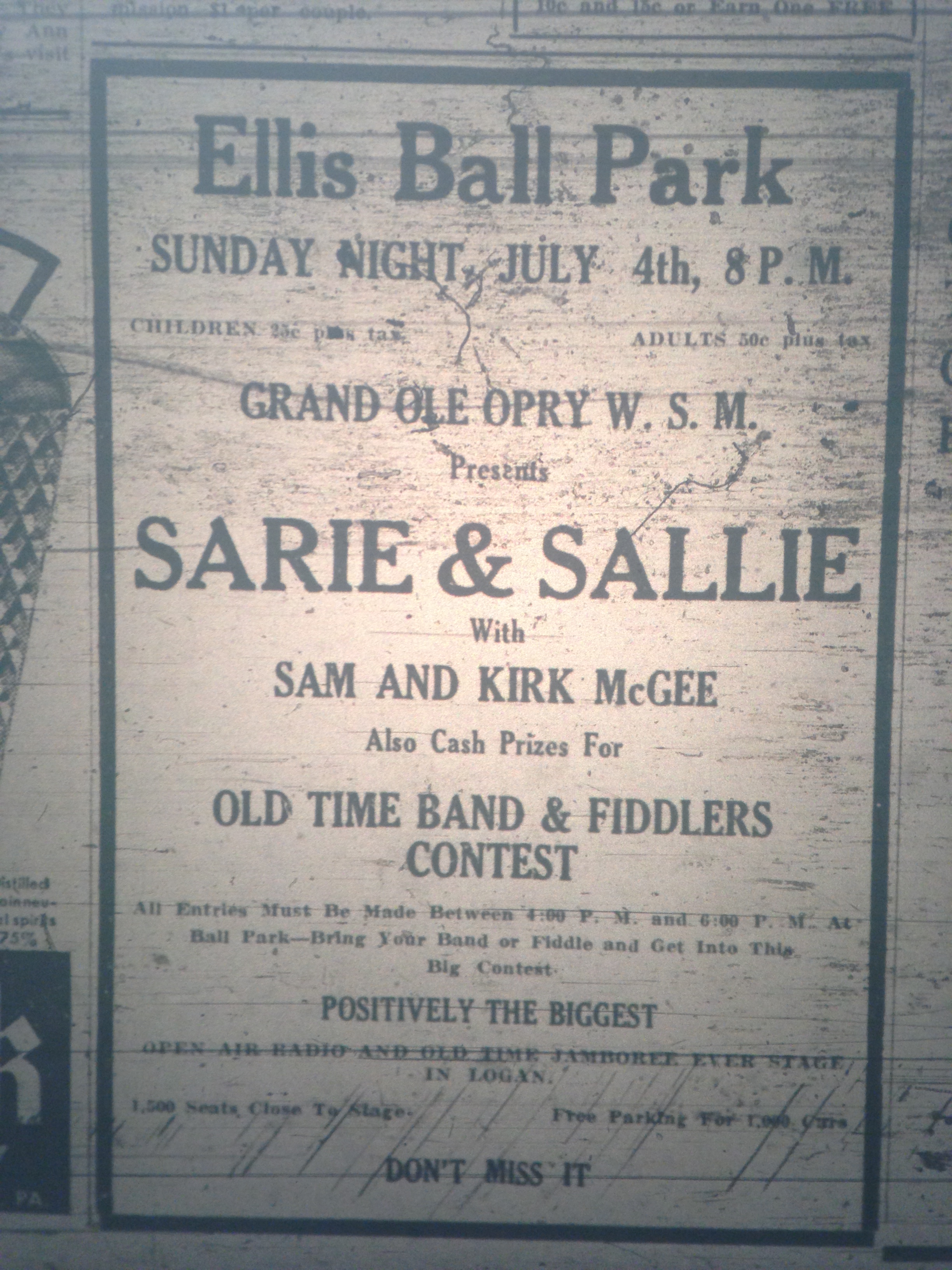

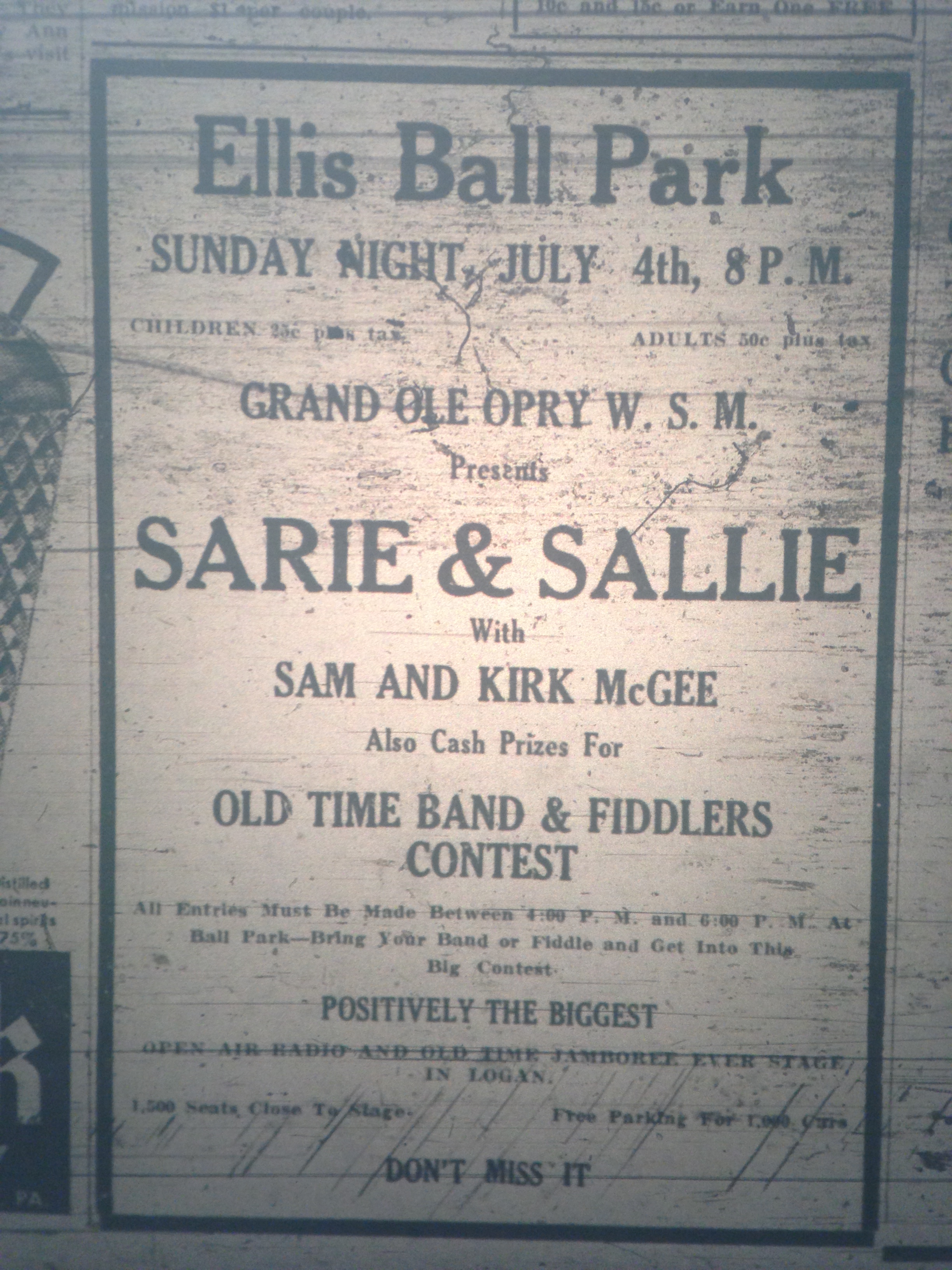

Logan (WV) Banner, 1 July 1937. 1500 seats!

18 Thursday Oct 2018

Tags

Appalachia, Ellis Ball Park, fiddlers, fiddling, Grand Ole Opry, history, Kirk McGee, Logan, Logan Banner, Logan County, music, Sam McGee, Sarie and Sallie, West Virginia

Logan (WV) Banner, 1 July 1937. 1500 seats!

21 Wednesday Jun 2017

Posted in Adkins Mill, Big Harts Creek, East Lynn, Harts, Lincoln County Feud, Music

Tags

Appalachia, Cain Adkins, Cain Adkins Jr., fiddler, fiddlers, genealogy, Grand Ole Opry, history, Lincoln County, Lincoln County Feud, Mariah Adkins, Matoaka, Mercer County, Mingo County, Mingo County Ramblers, Norfolk and Western Railroad, Raleigh County, West Virginia, Williamson, Winchester Adkins

Winchester Adkins (left) and Cain Adkins, Jr. (right), sons of Cain and Mariah (Vance) Adkins. Winchester (1874-1938) lived in Williamson, WV, where he was employed by the Norfolk and Western Railroad (and used the surname of Atkins). He was a fiddler who played on the Grand Ole Opry with a band called the Mingo County Ramblers. Cain Adkins, Jr. (1880-1943) lived in Matoaka, Mercer County, WV, and Raleigh County, WV. He was also a fiddler. Both men were children during their father’s involvement in the Lincoln County Feud. Photo courtesy of Adkins family descendants.

21 Monday Jul 2014

Posted in Calhoun County, Ed Haley, John Hartford, Music

Tags

Alabama, Arnoldsburg, Ashland, Bill Day, Brandon Kirk, Buttermilk Mountain, Calhoun County, Catlettsburg, Cincinnati, Doc White, Ed Haley, Ella Haley, England, fiddlers, fiddling, George Hayes, Grand Ole Opry, Great Depression, Harvey Hicks, history, Jean Thomas, Jilson Setters, John Hartford, Kentucky, Laury Hicks, Minnie Hicks, Mona Haley, music, Nashville, Nora Martin, Rogersville, Rosie Day, Sweet Florena, Ugee Postalwait, West Virginia, writing

I asked Ugee if Laury ever listened to the Grand Ole Opry and she said, “Yes. He got to hear it the year before he died. He got a radio. Let’s see, what is his name? George Hayes. We had Hayeses that lived down at Arnoldsburg. And he brought Dad up a little radio when Dad was down sick.”

Now, did Ed Haley ever hear the Grand Ole Opry?

“Oh, yes. He heard it down in Kentucky.”

Did he like it?

“No. He went to Cincinnati one time. They was a gonna make records — him and Ella — but they wanted to pick out the one for him to play. Nobody done him that a way. So he said, ‘I’ll pick my own.’ He went to Nashville once. I don’t know as he went to the Grand Ole Opry but he went to Nashville. Somebody drove him, took him down. But when he found out what they done, he didn’t have no use for that.”

Ugee made it clear that she had missed out on most of Ed’s wild times. She knew nothing about his running around with people like Doc White or chasing women. She did say he was bad about telling “dirty jokes.”

“Many a time he’s told me, ‘All right, Ugee. You better get in the kitchen. I’m gonna tell a dirty joke.’ And he’d tell some kind and you could hear the crowd out there just a dying over it. Ella’d say, ‘Mmm, I’ll go to the kitchen, too.'”

I asked Ugee about Ed’s drinking and she told the story again about her brother Harvey giving him drinks to play “Sweet Florena”. She sang some of it for me:

Oncest I bought your clothes, sweet Florena.

Oncest I bought your clothes, sweet Florene

Oncest I bought your clothes but now I ain’t got no dough

And I have to travel on, sweet Florene.

After finishing that verse, Ugee said, “That’s part of the song. And Ella didn’t like to hear that song. I think it reminded her of some of his old girlfriends or something. And she didn’t like for him to play ‘Buttermilk Mountain’, either. He’d throw back his head and laugh. She’d say, ‘Don’t play that thing. I don’t want to hear that thing.’ But she’d second it. She’d draw her eyes close together.”

Brandon asked Ugee about her aunt Rosie Hicks, who was Laury’s sister and a close friend to the Haley family. She said Aunt Rosie was working in Ed’s home in Catlettsburg when she met Blind Bill Day (her sixth husband) during the early years of the Depression. It was a rocky marriage, according to Rosie’s only child, Nora (Davis) Martin.

“I was gonna tell you about him hitting Aunt Rosie,” Ugee said. “He came through the house and Aunt Rosie was upstairs quilting and all at once — Nora said she was in the kitchen cooking — and she heard the awfulest noise a coming down the stairs and said, ‘Mommy had old Bill Day by the leg and was bringing him bumpety-bump down the stairs, dragging him. Got him in the kitchen. He just walked up and hit her with that left hand right in the mouth. She just jerked his britches off of him and started to sit his bare hind-end on the cook stove — and it red hot.’ And Nora said, ‘Oh, Mommy, don’t do that. You’ll kill him.’ She said, ‘That’s what I’m a trying to do.’ And she grabbed her mother and him both and jerked them away from there.”

Ugee was more complimentary of Day’s colleague, Jean Thomas.

“I’ve got cards from her and letters and pictures,” she said. “I’ve been to her house — stayed all night with her. She was nice. She was too good to Bill Day. She spent money on him and give him the name of Jilson Setters. Sent him to England and he played for the queen over there.”

Brandon wondered if Bill Day was a very good fiddler.

“Well, I’m gonna tell ya, I stayed all night with Aunt Rosie and Bill Day one time,” Ugee said. “They lived on 45th Street in Ashland, Kentucky. My brother took me and my mom down there and he hadn’t seen Aunt Rosie for a long time. She’d married again and she lived down there in Ashland, Kentucky. And we aimed to see Ed and Ella, but they was in Cincinnati playing music. That’s who we went to see. So Harvey, he filled hisself up with beer. That’s the first time I ever seen a quart bottle of beer. Anyway, we went up there to hear Uncle Bill play. Harvey laid down on the bed like he was sick. He wasn’t sick: he wanted me just to listen to that fellow play that fiddle. He knowed I’d get sick of it. And he played that song about the Shanghai rooster. I never got so tired in my life of hearing anything as I did that. He only played three pieces. Harvey laid there, he’d say, ‘Play that again. I love it.’ And I had to sit there and listen to it, ’cause I didn’t want to embarrass him by getting up and walking out. I walked over to Harvey and I said, ‘You’re not sick and you’re not tired, so you get up.’ Said, ‘Ugee, I’ve got an awful headache. I drove all the way down here.’ I said, ‘That bottle that you drank give you the headache, so you get up and you listen to your Uncle Bill.’ He went to the toilet. I said, ‘I’m telling you right now — you’re gonna listen to Uncle Bill if I have to listen to him.’ Harvey said, ‘I’m not listening to him no longer. I’ve heard all I want to hear of Uncle Bill.’ I got Harvey up and then I run and jumped in the bed and I covered my head up with a pillow. But we stayed all night and Aunt Rosie went home with us. She told him she’s a going up to Nora’s, but she went to Calhoun with us in the car, and I reckon while she’s gone old Bill tore up the house. I don’t think they lived together very long after that ’cause it wasn’t very long till she come back home. It was home there at my dad’s.”

Brandon asked if Day ever played with Ed in Calhoun County and Ugee said, “Oh, no. If he had, Dad woulda kicked him out.”

Okay, I thought: so Laury had no tolerance for lesser fiddlers. What about Ed?

“Ed Haley, if somebody was playing a piece of music and they wasn’t hitting it right, he’d stick his hands in his pockets and say, ‘Goddamn, goddamn,'” Ugee said. “Dad’d say, ‘Boy, ain’t he good?’ Ed would cuss a blue streak. Then after the man was gone, whoever it was, Dad and Ed would go to mocking him. Dad and Ed Haley was like brothers. They loved each other. Ella and Mom, too. Jack was the baby the first time I seen Ed after he was married. They was expecting Lawrence, so they named him after my dad. Then when she had Mona, why instead of calling her Minnie, she named her after Mom.”

16 Friday May 2014

Tags

Ashland, Atlanta, Bert Layne, Bill Day, Blackberry Blossom, blind, Clayton McMichen, Dill Pickle Rag, Ed Haley, Ed Morrison, Ella Haley, fiddle, fiddlers, Gary, Goodnight Waltz, Grand Ole Opry, history, Indiana, Jesse Stuart, John Carson, Kentucky, Lowe Stokes, mandolin, music, Ohio, Over the Waves, Portsmouth, Riley Puckett, Slim Clere, South Charleston, South Shore, Sweet Bunch of Daisies, Theron Hale, Vanderbilt University, Wednesday Night Waltz, West Virginia, World War I, WSM

The next day, after a few hours of sleep at Wilson’s house, Brandon and I drove to see fiddler Slim Clere in South Charleston, West Virginia. Slim was born in Ashland around the time of the First World War and knew a lot about Ed. We were parked behind his two-story house and were unloading our “gear” when he appeared out of a back door and led us inside his house (past some type of home recording studio) and up a flight of stairs. We sat down in the living room where we met his wife, a vivacious middle-aged woman who fetched several scrapbooks at Slim’s request. We flipped through the pages while Slim told us about some of his early experiences.

“I knew Jesse Stuart in 1934,” he said. “He lived at South Shore, Kentucky, across the river from Portsmouth, Ohio. He went to Vanderbilt. I believe he did play football. He used to date Theron Hale’s daughter that used to be at WSM at the Grand Ole Opry. I thought maybe he might marry her but he didn’t. Well anyway, I went away. I left my home and went to Atlanta. Well I went to Gary, Indiana, and everywhere, and worked with Bert Layne and Riley Puckett and some of those old-timers. I knew old Fiddlin’ John Carson. I never did meet Lowe Stokes. He lost an arm in a hunting accident. At one time he was a better fiddle player than McMichen. But Mac come out of it. He really could play. I patterned a lot of my style after him.”

Slim pointed to a picture of himself in his youth and said, “That’s back when I had hair and teeth.”

I was anxious to talk about Ed, so I asked Slim if he could remember the first time he ever saw him.

“I grew up knowing him,” Slim said. “He used to come down to the Ashland Park there every Sunday and sit around and fiddle for nickels and dimes on a park bench and I’d sit on there and watch him play.”

Slim said Ed Haley, Ed Morrison, and Bill Day were his primary influences during his younger days in Ashland.

“He was hot stuff,” Slim said of Haley.

He described Ed as a “loner” but said his wife was always with him.

“The old lady chorded a taterbug mandolin,” he said.

Ed played on a little yellow fiddle, which he wouldn’t let anyone “get a hold of,” and kept a cup between his legs for money. Down at his feet on the ground was his old wooden case, “made like a coffin.”

How much would you have to put in the cup to get him to play a tune?

“Didn’t matter,” Slim said.

Could he tell how much you dropped into the cup?

“He’d know just to the tee what it was,” he said. “He could tell the difference between a penny and a dime.”

Would the length of how long he played the tune depend on how much you dropped in the cup?

“No, he liked to play.”

Slim and I got our fiddles out and played a lot of tunes — or parts of tunes — back and forth for about a half an hour. I wanted to know all about Ed’s technique and repertoire. Slim said he “cradled” his fiddle against his chest (“all the old-timers used to do that”) and held the bow way out on the end with his “thumb on the underneath part of the frog.” He moved very little when playing.

“The only action he had was in that arm…and it was smooth as a top,” Slim said. “He fingered his stuff out. He didn’t bow them out. He played slow and beautiful and got the melody out of it. Now, he could play stuff like ‘Dill Pickle Rag’ where you had to cross them strings and that ‘Blackberry Blossom’ was one of his favorites. He played ‘Goodnight Waltz’, ‘Wednesday Night Waltz’. I don’t think ‘The Waltz You Saved For Me’ had been invented yet. He played ‘Over the Waves’ and ‘Sweet Bunch of Daisies’. He didn’t double-stop it, though.”

18 Friday Apr 2014

Tags

Appalachia, Ashland, Curly Wellman, Dunbar, Ed Haley, Ella Haley, fiddling, Grand Ole Opry, history, John Hartford, Judge Imes, Kentucky, Mona Haley, music, Pat Haley, Ralph Haley, writing, You Can't Blame Me For That

After visiting Curly and Wilson, I went to Pat Haley’s and met Mona, who was waiting to see me. Mona and I sat down at the kitchen table, while Pat washed dishes. It was my first visit with Mona in some time. I told her about visiting Curly Wellman, hoping to stir a memory, but she didn’t even remember him. I pulled out his picture and she and Pat both really bragged on his looks.

“He must have been a hunk when he was young,” Mona said. “You know, I always fell in love with guitar players.”

We all laughed and things got kind of loud, which caused Pat’s two little housedogs, Shady and Josie, to bark furiously from under the table. A few seconds later, after Pat’s commands had calmed the dogs, Mona surprised me by saying that she had heard “all her life” that Curly was the person who taught her brother Ralph to play the guitar. (It was actually the other way around.)

I had a lot of questions for Mona, who was exuding an openness I had not seen up to that point. It was obvious that she was going to be more candid in Lawrence’s absence. Before I could ask anything, she apologized for having not been more helpful in my efforts to know about Ed. I quickly pointed out, though, that she had been helpful, especially in regard to “the family troubles.” That aspect of Ed’s life was really important because it likely helped to explain a lot of the rage and lonesomeness I heard in his music.

“I wasn’t really scared of Pop,” Mona said. “I loved Pop. I just didn’t like the way he done Mom. It hurt all of us kids, I guess. The earliest memories I got is of me running away from Pop fighting with Mom and that has a whole lot to do with me not getting close to him like I did my mother. I think my mother was a remarkable woman. She probably taught Pop a lot of that music, too.”

I told her what Lawrence had said about Ed and Ella getting a “bed and board divorce” and she said, “No, I remember Mom did divorce him because she got Judge Imes to do the divorce. I think she divorced him when we lived on 17th Street. I never looked at them as being divorced because they had long since stopped being man and wife before they divorced.”

I got some paper from Pat’s granddaughter and asked Mona to describe Ed’s residence at 17th Street. In addition to serving as Ed’s home at the time of his divorce from Ella, it was also the place where he made his recordings. Mona described the downstairs, then the upstairs where “there was two bedrooms and a bathroom. Large bedrooms.”

After I’d sketched everything out based on Mona’s memory, she said, “I was gonna tell you about that living room couch that you drew the picture of with the radio on the end of it. I went in one day and I was just a teenager or young kid and I turned on some jitterbug music. Pop was laying on the couch and he said, ‘Turn that off,’ and I said, ‘No Pop, I want to hear it.’ And he said, ‘Mona, I’ll cuss you all to pieces.'”

Speaking of radios, I wondered if Ed ever listened to the Grand Ole Opry.

“No, I don’t think so,” Mona said. “He listened to mysteries, like ‘The Shadow’ and ‘The Green Hornet’ and all that kind of stuff. And ‘Amos ‘n Andy’ and ‘Little Abner.’ ‘Lone Ranger’, I remember that. And those opera singers, he called them belly shakers.”

While I had the pen and paper in hand, I asked Mona to describe Ed’s house at Ward Hollow.

“Well, they was a porch, then a living room, dining room, and kitchen — straight back — and all the way down through here was another bedroom and hallway and another bedroom. Then in through here was a bathroom and back here was another bedroom. That’s where Pop slept. And right off the kitchen was another little porch.”

Mona said she could draw it better than describe it to me, so I gave her a pen and some paper. When she was finished, she seemed pleased with her effort, saying, “I might have a good memory after all.”

Satisfied, I got out my fiddle and played some tunes for Pat and Mona. After I finished “Dunbar”, I told them how I figured it was one that Ed made up.

“See,” I said, “I’ve got all these lists of tunes at home and lists of tunes on other tapes and so I look these tunes up and try to find out where they come from. And some of them you can research and some of them just ain’t there and those are the ones I think he wrote.”

Mona figured Ed made the tune “You Can’t Blame Me For That”:

My dog she’s always fighting, in spite of what she loves.

And when her little pups was born we all wore boxing gloves.

An old hen once was sitting on twelve eggs. Oh, what luck!

She hatched 11 baby chicks and the other was a duck.

But you can’t blame me for that, oh no, you can’t blame me for that.

If a felt hat feels bad when it’s felt, you can’t blame me for that.

I got the impression in watching Mona sing those words to me that she was able to picture Ed playing.

05 Saturday Apr 2014

Tags

Appalachia, Ashland, Calhoun County, Ed Haley, Ella Haley, fiddle, fiddlers, fiddling, Grand Ole Opry, history, John Hartford, Kentucky, Logan County, music, Nora Martin, Rosie Day, U.S. South, Ugee Postalwait, West Virginia, writing

I got my fiddle back out to play more for Ugee. When I finished “Going Across the Sea”, she said, “I’ve heard that. ‘Blackberry Wine’, that’s what he called it. They got ‘high’ on it. Dad and Ed would play it and say, ‘Boy you got a little high on that wine that time, didn’t ya?’ That meant they was getting smoother on the playing.”

I played more tunes for Ugee, who said, “You’re better on that there ‘Ed Haley playing’ than what you was the last time I heard you.”

A few tunes later, she said, “That makes me think of Dad’s fiddling.”

Harold said, “You ought to hear him play your dad’s fiddle.”

I said, “Do you want to hear me play it?”

Harold disappeared into another room and returned with Laury’s fiddle. It was in great condition. I tuned it up and played for Ugee, who just sat there quietly. I could see her emotions churning as she thought back to happy memories of her father. She was almost in tears.

“I didn’t know I’d ever hear my dad’s fiddle played again,” she said. “Last time I ever heard it played was in my dreams.”

I played Ugee a few tunes on her father’s fiddle and she said, “You like to play the fiddle. It’s hard to find good fiddlers. But since you went and loosened up on that bow down there, you’ve really got better on that. I don’t know music, but I can tell it when I hear it ’cause I was raised in a house where Dad played the fiddle, and Ed Haley.”

I played another tune for Ugee and she said, “Can you picture two fiddlers playing like that on the porch? Maybe play all day. You couldn’t play an old tune that I haven’t heard my dad and Ed Haley play ’cause they knowed them all. And it didn’t take them but a second to learn them. I’d have to learn the words to sing a song and Dad — maybe I would sing it to him about twice — and then we’d go someplace and he’d sing it. Now that’s just how quick he could catch on. Then he’d sit down and practice and smooth it out.”

Ugee told me about Laury’s final years. She said when he started feeling ill, he visited his sister Rosie Day in Ashland and his niece Nora Martin in Logan. It was his farewell tour, in a way. Ugee said he located Ed at Nora’s in what was maybe their last visit together. Once Laury made it back to Calhoun County, he slept in a chair because he was afraid he might never get up from bed. Eventually, though, he “took to his bed,” where he remained for a few years. He didn’t have a lot of company — he didn’t want Ed to see him in such poor condition. He purchased a radio and listened faithfully to the Grand Ole Opry. Every now and then, he’d get inspired to play.

“Ugee, come here,” Laury said during one of those times.

“What do you want, Dad?” Ugee answered, walking in to the room.

“Get behind me,” he said. “I’ve got to set up.”

“Okay,” she said, getting behind him.

“Now hand me the fiddle,” he said.

“I can’t and you there leaning again’ me,” she said.

“Ida, bring me my fiddle,” he told her.

Ugee said he sat there and “see-sawed and played that fiddle for me. I never got so tired in all my life. I thought I’d die.”

“Honey, I know I’m heavy on you,” he said.

“It ain’t hurting me a bit Dad,” Ugee fibbed.

When Laury was done playing, he looked up and said, “I want this fiddle give to Harold. I want Harold to have my fiddle.”

“That was the last time I seen him play the fiddle,” Ugee said. “He told me, ‘Wait till I get better and we’ll have some good music in the house.'”

30 Sunday Mar 2014

Tags

Appalachia, Calhoun County, Cincinnati, Ed Haley, fiddlers, fiddling, Grand Ole Opry, Great Depression, Harold Postalwait, history, John Hartford, Laury Hicks, Minnie Hicks, music, Nashville, Ohio, Ugee Postalwait, West Virginia, Wilson Douglas, writing

I said, “Now when they played, would they play at the same time?”

“Oh yeah,” Ugee said. “Sometimes they played at the same time. Then one time maybe one would be a playing and the other would be a listening. Say, ‘Oh, you pulled that bow the wrong way.’ ‘Now that didn’t sound right to me. Go back over that again.’ They’d sit maybe not for ten minutes but for hours at a time when I was a growing up. Trying to out-beat the other. Which could make the best runs and which could do this. They never was mad at each other or anything like that, but they’d argue about it. ‘I know I beat you on it.’ ‘Well, you put that run in it at the wrong place.’ But Ed Haley is the only man I ever heard in my life second the fiddle. Dad’d play the fiddle and he’d second his with the fiddle. Like if you’re playing the ‘fine,’ why he might be playing the bass. That’s the prettiest stuff ever you heard. I heard Dad try to do it but Dad never got that good on it.”

I asked her if Ed ever played “Flannery’s Dream” and she said, “Oh, yeah. I’ve heard that.”

When I played “Wild Hog in the Red Brush”, she said Ed definitely played it, although she didn’t remember it having that title.

Just before I played another tune, Ugee said, “This is my birthday gift. My birthday’s the 19th. I’ll be 88 years old. Oh, I do pretty good, I reckon, for the shape I’m in. I remember pretty good but I’ve got trouble on this here voice box.”

“You remember pretty good, like your mother,” Harold said. “She was a hundred years old and she remembered when every kid was borned in that part of the country.”

Ugee said, “Mom delivered over five hundred children. She knowed every one of them and their name.”

Harold said, “And where they come from and up what hollow she had to walk and everything else. She never forgot nothing, that woman.”

Ugee said, “I don’t want to be that old. It’s all right if you can walk and get around. But if you’re down sick in the nursing home, let the good Lord take me away. I don’t wanna be there. My dad had leukemia and cancer of the stomach when he died. And it’s hard to see someone suffer like that.”

I told Ugee what Wilson Douglas had said about people gathering at her father’s home and listening to music on the porch and she said, “Sure, you ought to have seen my home. We had one porch run plumb across the front of the house. Ed and Dad just sat right along behind the railing.”

She pointed to the picture of John Hicks’ house and said, “Our house was even bigger than that. It was plank. But I remember when they all come over there and they’d gang around on that porch. Everybody. When Ed Haley was in the country, they come from miles around to our house. Word would get out that Ed was there or Ed was gonna be there a certain day.”

Inspired by Ugee’s memories, I got some paper from Harold and tried to sketch the Laury Hicks place. Ugee said things like, “It didn’t have no fireplace — we had gas then. And over on this end the steps went plumb down the hill to the road. That’s after they put the paved road down there, you see. Our house sat almost in a curve. Garage is down there at the road.”

I said, “So people gathered in front of the porch to hear all the music?” and Harold said, “They didn’t have much room. The yard only went out there maybe thirty or forty feet and then it dropped off down to the road. A pretty steep bluff — fifteen-, eighteen-, twenty-foot drop. On this side of the house was the garden spot and out the other end the yard didn’t go very far.”

Were there shade trees around the house?

“Yeah, three or four big oak trees over to one side and then we had apple trees on the other side,” Ugee said.

I asked if the crowds came at day or night or only on weekends and Ugee said, “They’d come through the day and Dad and Ed would play music all day and half the night. Weekends, why, it was always a big crowd. I’ve studied about them so much, about how good a friends Ed and Dad was. And always was that way. And they’d have the most fun together.”

Ugee said Ed never put a cup out for money.

“I never seen him put a cup out in my life. Maybe they’d be somebody to come around and put a cigar box to the side and everybody would go through and put money in it. Course when he was playing in the city — Cincinnati or some place like that — why he’d make quite a bit of money there. Whenever he played them religious songs, the hair’d stand on your neck. You’d look at two blind people sitting and singing.”

I interrupted, “Did he play Cincinnati a lot?”

Ugee said, “He played Cincinnati a lot. He went to Cincinnati to make records one time, too. That’d a been in the thirties. He fell out with them. They wanted to pick the tunes. Ain’t nobody picked tunes for Ed — Ed picked his own tunes. When he found out what they was trying to hook him on, he quit right then. Ed went down to Nashville once. I don’t know that he went to the Grand Ole Opry but he went to Nashville. When he found out what they done, he didn’t have no use for that.”

04 Tuesday Mar 2014

Posted in Big Ugly Creek, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Big Ugly Creek, Bill Monroe, Boney Lucas, Carl Toney, charlie paris, Clarence Lambert, Durg Fry, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Frank Fry, Grand Ole Opry, Green Shoal, Guyandotte River, history, Irvin Lucas, Jack Lucas, Jim Lucas, Jupiter Fry, Leander Fry, music, Paris Brumfield, Sam Lambert, writing

At the turn of the century, Jim Lucas was the best fiddler on Big Ugly Creek — that peculiarly named creek located a few miles downriver from Harts Creek. Jim was born in 1881 to Irvin Lucas (a fiddler), and was a nephew to Boney Lucas and Paris Brumfield. Based on interviews with Jim’s family, Jim always went clean-shaven and wore an overcoat year round because “whatever’d keep the cold out would keep the heat out.” He was also an avid hunter and cowboy — he could supposedly command cattle from across the Guyan River. As for his fiddling, Jim either cradled the fiddle on the inside of his shoulder or held it under his chin. He gripped the bow with two or three fingers right on its very end, used a lot of bow, and patted one of his feet when playing. He sometimes sang, typically played alone, and devoted a great deal of his time fiddling for children. Every Saturday, he’d get with Clarence Lambert at his home on the Rockhouse Fork of Big Ugly or at Sam Lambert’s porch on Green Shoal. Some of Sam’s daughters sang and played the guitar. Jim’s grandson Jack Lucas said they played a lot of gospel and bluegrass music but could only remember one tune Jim played: “Ticklish Reuben.” Jim had to give up the fiddle when he got old but always put an almost deaf ear up against the radio and listened to Bill Monroe on the Grand Ole Opry. He died in 1956.

Charlie Paris, a long-time resident of the Laurel Fork of Big Ugly Creek, remembered Jim Lucas coming to visit his grandfather Durg Fry in the thirties. He said his grandpa Durg lived on Laurel Fork in a home with cracks between the logs so large that “you could throw a dog through” them. He was a fiddler himself, as were his brothers Leander and Jupiter and his nephew Frank Fry. Charlie said Durg played with the fiddle under his chin and never sang or played gospel or bluegrass. He patted his feet when playing and, in his old age, would hold himself up by a chair and dance to music. One time, when he and Jim were hanging out on Laurel Fork, Jim reached his fiddle to a younger fella named Carl Toney and said, “Your turn.” Carl was a very animated fiddler and when he took off playing “Orange Blossom Special” Jim just shook his head and said, “I’ve quit.”

13 Thursday Feb 2014

Posted in Big Sandy Valley, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Billy Adkins, Cain Adkins, fiddle, fiddler, Grand Ole Opry, Harts Creek, Lincoln County, Mingo Ramblers, Norfolk and Western, Stiltner, Tom Atkins, Wayne County, West Virginia, Williamson, Winchester Adkins, writing

A week later, I followed up on a lead from Billy Adkins and called Tom Atkins. Tom was a great-grandson of Cain Adkins and a genealogist in Williamson, West Virginia. It was a chance lead: Billy had called him to ask about Ed Haley’s genealogical connections in the Tug Valley only to discover that Tom’s grandfather was Winchester Adkins — a son to Cain.

When I called Tom, he said he knew almost nothing about Cain and only a little about his grandfather, Winchester Adkins. He said Winchester left the West Fork of Harts Creek at a young age and settled at Stiltner in Wayne County. He eventually moved to Williamson and worked as an engineer on the N&W Railroad. At that location, after a repeated “mix-up over his checks” he changed the spelling of his surname from “Adkins” to “Atkins.” He was also a well-known fiddler who tried his hand at professional music.

“I heard my mother tell someone here while back how many tunes my grandfather played,” Tom said. “It was a hundred and some. See, he just knew them by ear. And I believe that at one time he had a fiddle that was made by Cain — his father — and I don’t know who has that or whether it’s even in existence now ’cause we’ve had floods here. And I do know at one time he was a member of a group in Mingo County called the ‘Mingo Ramblers’ and they were on the Grand Ole Opry way back in the early days.”

Tom said that was all he knew because his grandfather died when he was four years old.

10 Friday Jan 2014

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Appalachia, Arthur Smith, banjo, Ed Belcher, Ed Haley, fiddlers, George Mullins, Geronie Adams, Grand Ole Opry, Harts Creek, history, Joe Adams, Johnny Hager, Logan County, music, Robert Martin, West Virginia, writing

I wondered if people around Trace listened to the radio, especially the Grand Ole Opry, in the early days.

“They was a few radios,” Joe said. “We had one here. We ordered it from a company called Jim Brown. It had five batteries. And like Jerry Clower said, you’d take them and set them in front of the fire and get them hot and then plug them in, they’d play. They was kindly hard to get — they didn’t cost much. I think they was about ten or twelve dollars for all of them. But Robert Martin had one on top of that hill and my brother had one on Twelve Pole, and on Saturday night when the Grand Ole Opry come on, it was a sight to watch these people a going. It come in good and clear. Robert learned a lot of Arthur Smith tunes off the radio. Yeah, Arthur Smith come down there at Branchland and stayed a week with him and I was talking to Robert after he left and he said, ‘I wish you boys’d come down.’ I said, ‘Well, if you’d a let us know, we woulda come.'”

Brandon said to Joe, “I remember you were telling me last time I talked to you that you thought Robert Martin was about the best around.”

Joe said, “In the modern music. Now, in the old-time music, you’d take Ed Haley and Johnny Hager and Ed Belcher. Ed Belcher, he stayed at George Mullins’ and he was like my brother: he was an all around musician. He could tune a piano and play it, he could play an organ. He could play anything he picked up. I never did hear him play a banjo but he could play anything on the fiddle or guitar. He’d note the guitar all the time. He played like these fellers play on Nashville. They was several people around here had banjos and played. Geronie Adams — Ticky George’s boy — he played a banjo a little bit. And they was a fella — Johnny Johnson — played with Robert Martin out on that hill. He was from someplace in Kentucky.”

I asked Joe what kind of banjo style Johnny Hager played.

“He played the old…,” he started. “They’s some of them calls it the ‘overhand’ and some of them call it just ‘plunking’ the banjo. They was several people played like that. Bob Dingess down here, he played that a way a little bit. My dad, he played the banjo and he played that.”

I asked Joe how Ed dressed in the early forties.

“Well, he wore dress pants most of the time,” he said. “He wore mostly colored shirts — blue or green or just any color. Work shirts. Most of the time he wore suspenders with them. And had buttons sewed on them to buttom them with. Buttons on the inside. Mostly he wore slippers. They was a lace-up slipper. Three laces. He could tie his shoes just as good as you could tie yorn. He wasn’t a big man — he was a little small man. About 5’4″, 5’5″.”

Brandon asked what Ed was like when he wasn’t playing and Joe said, “Well, he’d just sit around and talk and tell tales about first one thing and then another. They’d just talk about how hard they was raised and how they come up.”

Did the ladies like him?

Joe said, “They all liked him but they wasn’t girlfriends. If he went into a place to play, they’d all come around and hug him and talk to him.”

12 Tuesday Feb 2013

Posted in Ashland, Big Sandy Valley, Ed Haley, Music

Tags

Ashland, Big Sandy River, Blackberry Blossom, Blaze Starr, Bluegrass Meadows, Boyd County, Clark Kessinger, Dave Peyton, Delbarton, Duke Williamson, Ed Haley, fiddle, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Georgia Slim Rutland, Grand Ole Opry, Hank Williams, Herald-Dispatch, history, Huntington, Jennies Creek, John Fleming, John Hartford, Kentucky, Lawrence Haley, Lynn Davis, McVeigh, Mingo County, Minnie Pearl, Molly O Day, Molly O'Day, music, Parkersburg Landing, Pike County, Pond Creek, Short Tail Fork, Shove That Hog's Foot, Skeets Williamson, Snake Chapman, Texas, West Virginia, Williamson

Early that summer, I was back at Lawrence Haley’s in Ashland with plans to visit Lynn Davis in Huntington, West Virginia. Lynn had been mentioned in the Parkersburg Landing liner notes as a source for Haley’s biographical sketch and was the widower of Molly O’Day, the famous country singer. Snake Chapman had told me that Molly and her family were close friends to Haley, who visited their home regularly in Pike County, Kentucky. I was sure Lynn would have a lot of great stories to tell about Ed. At our arrival, he was incredibly friendly — almost overwhelming us with the “welcome mat.” All we had to do was mention Ed’s name and he started telling us how he and Molly used to pick him up in Ashland and drive him up the Big Sandy Valley to see Molly’s father in southeastern Kentucky.

“That was back in the early forties,” he said. “We’d come to Ashland and get him at his home up on Winchester about 37th Street. They was a market there or something you turned up by and we’d go there and pick him up and take him up to Molly’s dad and mother up in Pond Creek, Kentucky — above Williamson. There’s an old log house up there — it’s been boarded up and sort of a thing built around it so people couldn’t get in and tear it up or something — but it’s falling down. He’d stay up there with Molly’s dad and mother for several days. They’d take him to Delbarton, a coal town over there from Williamson, and they’d just drive him around, buddy. Now Molly’s brother, he really loved Ed’s fiddling.”

Lynn was referencing Skeets Williamson, Molly’s older brother and a good fiddler by all accounts. Lynn showed me an album titled Fiddlin’ Skeets Williamson (c.1977), which referenced him as “one of country music’s more skilled fiddlers during the 1940’s — one of the best in his day.”

Skeets was born in 1920 at McVeigh, Kentucky, meaning he was approximately 35 years younger than Haley. As a child, he played music with Molly and his older brother Duke Williamson, as well as Snake Chapman. “During these years, the famous fiddler of Eastern Kentucky, Blind Ed Haley, became a tremendous influence on him,” the album liner notes proclaimed. “Skeets (along with Clark Kessinger) still contend that Haley was the greatest fiddler who ever played.” During a brief stint on Texas radio, Skeets met Georgia Slim Rutland, the famous radio fiddler who spent a year listening to Haley in Ashland.

I asked Lynn more about his trips to Haley’s home on 37th Street.

“We used to go down to his house and Molly’d say, ‘Uncle Ed, I’d just love to hear you play me a tune.’ Well he’d be sitting on the couch and he’d just reach over behind the couch — that’s where he kept his fiddle. He always had it in hand reach. So he would get it out of there, man, and fiddle.”

Sometimes Lynn and Molly would join in, but they mostly just sat back in awe.

“You’ve seen people get under the anointing of the Holy Ghost, John,” Lynn said. “Well now, that’s the way he played. I mean, I’ve seen him be playing a tune and man just shake, you know. It was hitting him. I mean, it was vibrating right in his very spirit. Molly always said, ‘I believe that fiddlers get anointed to the fiddle just like a preacher gets anointed to preach.’ They feel it. Man, he’d rock that fiddle. He’d get with rocking it what a lot of people get with bowing. It was something else. But he got into it man. He moved all over.”

Lynn said Ed was a “great artist” but had no specific memories of his technique. He didn’t comment on Ed’s bowing, fingering or even his fiddle positioning but did say that he mostly played in standard tuning. Only occasionally did Ed “play some weird stuff” in other tunings.

Lynn’s memories of Haley’s tunes seemed limited.

“Well, he played one called ‘Bluegrass Meadows’,” he said. “He had some great names for them. Of course one of his specials was ‘Blackberry Blossoms’. He liked that real good, and he’d tell real stories. He would be a sawing his fiddle a little while he was telling the story, and everybody naturally was just quiet as a mouse. You know, they didn’t want to miss nothing.”

What kind of stories?

“Well, I know about the hog’s foot thing. He said they went someplace to play and they didn’t have anything to eat and those boys went out and stole a hog and said they brought it in and butchered it and heard somebody coming. It was the law. They run in and put that hog in the bed and covered it up like it was somebody sleeping. And Ed was sitting there fiddling and somebody whispered to him, said, ‘Ed, that hog’s foot’s stickin’ out from under the cover there.’ So he started fiddling and singing, ‘Shove that hog’s foot further under the cover…’ He made it up as he went.”

The next thing I knew, Lynn was telling me about his musical career. He’d been acquainted with everybody from country great Hank Williams to Opry star Minnie Pearl. We knew a lot of the same people — a source of “bonding” — and it wasn’t long until he started handing me tapes and records of Molly O’Day and Georgia Slim Rutland. He said he had a wire recording of Ed and Ella somewhere, but couldn’t find it. He promised me though, “When I find this wire — and I will find it — it’s yours.”

Sometime later, he called Dave Peyton, a reporter-friend from the Huntington Herald-Dispatch, to come over for an interview. With Peyton’s arrival, Lynn (ever the showman) spun some big tales.

“Now, Molly’s grandfather on her mother’s side was the king of the moonshiners in West Virginia and he was known as ‘Twelve-Toed John Fleming’,” Lynn said. “He had six toes on each foot. Man, he was a rounder. Little short fella, little handlebar mustache — barefooted. He was from the Short Tail Fork of Jenny’s Creek. And the reason they called it that, those boys didn’t have any britches and they wore those big long night shirts till they was twelve or fourteen years old.”

Lynn was on a roll.

“I preached Molly’s uncle’s funeral. Her uncle is the father of Blaze Starr — the stripper. That’s Molly’s first cousin. In her book, she said she would walk seven miles through the woods to somebody that had a radio so she could hear her pretty cousin Molly sing. She was here in town about three or four months ago. We had breakfast a couple times together. She’s not stripping anymore. She makes jewelry and sells it. She’s about 60 right now.”

13 Sunday Jan 2013

Posted in Ed Haley

Tags

Appalachia, Ashland, banjo, Billy in the Lowground, Blackberry Blossom, blind, Cacklin Hen, Catlettsburg, Clark Kessinger, Clayton McMichen, culture, Curly Wellman, Curt Polton, Ed Haley, Elvis Presley, fiddler, Floyd Collins, Forked Deer, Grand Ole Opry, guitar, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Horse Branch, Huntington, Ivan Tribe, John Hartford, Kentucky, Lawrence Haley, Logan County, Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round, Morehead, Mountain Melody Boys, Mountaineer Jamboree, music, National Fiddling Association, Old Sledge, Poplar Bluff, Rowan County Crew, Ugee Postalwait, Ward Hollow, WCHS, WCMT, Westphalia Waltz, writing, WSAZ

I asked Curly if he remembered any of Ed’s tunes and he said, “Ah, I remember ‘Forked Deer’ and I remember ‘Billy in the Lowground’ and I remember the ‘Old Sledge’ and I remember ‘Poplar Bluff.’ ‘Blackberry Blossom.’ The longer he played a tune, the meaner he got on it. If he got the feel, it hit him. And the more he played the better he got and the more tunes come to him. He played one waltz — ‘Westphalia Waltz’ — and that’s really the only waltz that I can recall that he played. And it was all double stop fiddle.”

Curly never heard Ed sing a note — a very surprising recollection considering the way that Ugee Postalwait had hyped Haley’s singing abilities.

“I got a copy of a song from him,” Curly said. “He had somebody to write it down. Because at this time, out at Morehead, Kentucky, they had a feud out there. And they had a shoot-out there on the steps and then somebody wrote this song called ‘Rowan County Crew.’ And Ed, they tell me, would sing that at different places throughout Kentucky. At that time, it was like Floyd Collins that was in the cave and like the Hatfields and the McCoys — only this was called the ‘Rowan County Crew.’ Well, at that time it was hot as a pistol through the state. Now evidently he sang that song, but he never sang it for me.”

Curly said, “Ed could have been as great as the Blue Yodeler or any of those people. He could have been right on those records with them but under no reason did he want to record commercially. Had he been living today and with the equipment they’ve got today, he would’ve been in more demand than Elvis Presley ever was. Nobody played ‘Cacklin’ Hen’ like him. And a very humble man. I never heard Ed down anybody else, I never heard him put anybody below him and I never had him to tell me how good he was. In fact, I wonder sometimes if he knew how good he was. But I knew it. He was a brilliant man. He’d just about keep a check up on everything during his lifetime. He knew the news, he knew the political field, he knew what was going on in the state.”

I asked Curly about the first time he ever saw Haley play.

“I played with Ed when I was a kid — twelve, thirteen years old — and we lived at a place called Horse Branch. That’s as you enter Catlettsburg, Kentucky. And I was a kid carrying an old flat-top guitar — no case — trying to learn how to play. In the evening, he’d come out on the front porch after dinner and Ralph would get the guitar and the mother would get the mandolin and the neighborhood would gather because at that time radio was just coming into being. And I’d go down there and sit and bang while they were playing. And that’s where I first heard Ed Haley.”

Curly lost track of Ed when he started playing music out on his own at the age of fifteen. Throughout the mid-thirties, he played over the radio on Huntington’s WSAZ and Ashland’s WCMT with the “Mountain Melody Boys,” then made several appearances on the Grand Ole Opry and Knoxville’s Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round with Curt Polton’s band. It was during that time, he said, around 1936, that Ed got into a contest with Clark Kessinger and Clayton McMichen at the WCHS radio station in Charleston. Clayton was the National Fiddling Champion, while Clark was the National Fiddling Association’s champion of the East. The whole thing was “built up for months — it was a showdown.” In the contest, each fiddler got to play two tunes and someone named Banjo Murphy seconded every one using a three-finger picking style on a four-string banjo. First prize was a “live baby” (a little pig) and the winner was determined by a clapping meter. Curly wasn’t sure what tunes Ed played (probably “Cacklin’ Hen,” his contest specialty) but remembered the results clearly.

“Ed Haley beat the two men on stage,” he said. “McMichen was out of it in a little bit but it took several rounds to eliminate Clark Kessinger.”

Curly returned to Ashland in the early forties and found Ed living in the bottom of a weather-boarded, two-story apartment building on 37th Street (Ward Hollow). He started visiting Haley again, usually on cold days when he knew that he’d be close to home. He’d put his D-18 flat-top Martin guitar in the trunk of his car and “go pick up a pint or a half a pint of moonshine,” then head on over to Ed’s house.

I’d go in. I wouldn’t take the guitar in at all. I’d just knock on the door and go in and I’d say, “Hi, Uncle Ed.” “Hi, Curly.” He knew me by my voice. And I’d go in and sit down, you know, and say, “How’s the weather?” and “How’s things?” and “How’s the family?” and so forth and so on. We’d sit around there and talk a little bit. I’d say, “Ed, been playing any lately?” “No, I haven’t felt like it. I just haven’t felt like it.” I’d say, “Well, how about a little nip? You think that would help?” “Well now you know you might have something there.” So I’d go on to the car and I’d get the bottle and come in and we’d sit back down and I’d pass it to him. He’d hit it. He’d sit right there a little bit you know and I’d say, “Take another little nip, Ed.” “Well, I believe I will,” he’d say. “It’s too wet to plow.” And he’d sit there and he’d rock a little bit in that chair and… Being blind, he talked a little loud. “Hey, did I ever play that ‘Old Sledge’ for you?” I’d say, “Well, I can’t remember Ed. Just can’t remember.” Well, he’d get up and he’d go over and he’d lay his hand right on that fiddle laying on the mantle of the fireplace. By that time I’d be out the door and getting the Martin. I’d come back in and he’d tune ‘er up there and feel her across you know and touch her a little bit here and there. He’d take off on it.

Curly and I got our instruments out and played a few of Haley’s tunes. He showed me the type of runs he used to play behind Ed and gave me a few more tips about his fiddling. He said Ed was “all fingers…so smooth” and could play all over the fingerboard — even in second and third positions. He “put a lot of his upper body into the fiddling” and patted one foot to keep time. If he fiddled for a long time, he put a handkerchief under his chin for comfort (never a chinrest) and dropped the fiddle down to his arm and played with a collapsed wrist.

Just before Lawrence and I left, Curly said, “I’ll tell you somebody that’s still living in Charleston and he’s a hell of a fiddle player — or was. They called him Slim Clere. He’s about 82. He knew Ed. In fact, he was the man that Clere looked up to as he was learning. And he could probably give you more information than I could because he’s followed the fiddle all of his life.”

Curly also recommended Mountaineer Jamboree (1984), a book written by Ivan Tribe that attemped to detail West Virginia’s contributions to country music. It briefly mentioned Ed: “Blind Ed Haley (1883-1954), a legendary Logan County fiddler who eventually settled in Ashland, Kentucky, repeatedly refused to record, but did belatedly cut some home discs for his children in 1946.”

26 Monday Nov 2012

Posted in Ashland, Big Sandy Valley, Ed Haley, Matewan, Music, Pikeville, Williamson

Tags

Appalachia, Art Stamper, Arthur Smith, Ashland, Big Sandy River, Billy Lyons, Blackberry Blossom, blind, Charles Wolfe, Clark Kessinger, Clayton McMichen, Duke Williamson, Ed Haley, fiddle, fiddler, fiddlers, fiddling, Fox in the Mud, Frazier Moss, Fred Way, Ft. Gay, Grand Ole Opry, history, Huntington, Joe Williamson, John Hartford, Kentucky, Kermit, Kirk McGee, Levisa Fork, Louisa, Mark Howard, Matewan, Mississippi River, Molly O'Day, music, Nashville, Natchee the Indian, Ohio River, Old Sledge, Packet Directory, Paintsville, Parkersburg Landing, Pikeville, Prestonsburg, Red Apple Rag, River Steamboats and Steamboat Men, Robert Owens, Roy Acuff, Sam McGee, Skeets Williamson, Snake Chapman, square dances, St. Louis, Stacker Lee, Stackolee, steamboats, Tennessee Valley Boys, Tri-State Jamboree, Trouble Among the Yearlings, Tug Fork, West Virginia, Williamson, WSAZ

Back in Nashville, I was knee-deep in Haley’s music, devoting more time to it than I care to admit. I talked so much about it that my friends began to tease me. Mark Howard, who was producing my albums at the time, joked that if Ed’s recordings were of better quality, I might not like them so much. As my obsession with Haley’s music grew, so did my interest in his life. For a long time, my only source was the liner notes for Parkersburg Landing, which I had almost committed to memory. Then came Frazier Moss, a fiddling buddy in town, who presented me with a cassette tape of Snake Chapman, an old-time fiddler from the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy in eastern Kentucky. On the tape, Snake said he’d heard Haley play the “old original” version of “Blackberry Blossom” after he “came in on the boats” at Williamson, West Virginia.

The boats?

This was making for a great story. I was already enthralled by Haley’s fiddling…but to think of him riding on “the boats.” It was the marriage of my two loves. I immediately immersed myself in books like Captain Fred Way’s Packet Directory 1848-1983: Passenger Steamboats of the Mississippi River System Since the Advent of Photography in Mid-Continent America (1983) to see which boats ran in the Big Sandy Valley during Haley’s lifetime. Most of the boats were wooden-hulled, lightweight batwings – much smaller than the ones that plied the Mississippi River in my St. Louis youth – but they were exciting fixtures in the Big Sandy Valley culture.

“I have seen these boats coming down the river like they were shot out of a cannon, turning these bends, missing great limbs hanging over the stream from huge trees, and finally shooting out of the Big Sandy into the Ohio so fast that often they would be nearly a mile below the wharf boat before they could be stopped,” Captain Robert Owens wrote in Captain Mace’s River Steamboats and Steamboat Men (1944). “They carried full capacity loads of sorghum, chickens and eggs. These days were times of great prosperity around the mouth of Sandy. Today, great cities have sprung up on the Tug and Levisa forks. The railroad runs on both sides, and the great activity that these old-time steamboats caused has all disappeared.”

During the next few weeks, I scoured through my steamboat photograph collection and assembled pictures of Big Sandy boats, drunk with images of Haley riding on any one of them, maybe stopping to play at Louisa, Paintsville, Prestonsburg and Pikeville, Kentucky on the Levisa Fork or on the Tug Fork at Ft. Gay, Kermit, Williamson, and Matewan, West Virginia.

Finally, I resolved to call Snake Chapman and ask him about his memories. It was a nervous moment – for the first time, I was contacting someone with personal memories of Ed Haley. Snake, I soon discovered, was a little confused about exactly who I was and why I was so interested in Haley’s life and then, just like that, he began to offer his memories of Ed Haley.

“Yeah, he’s one of the influences that started me a fiddling back years ago,” Snake said, his memories slowly trickling out. “I used to go over to Molly O’Day’s home – her name was Laverne Williamson – and me and her and her two brothers, Skeets and Duke, used to play for square dances when we first started playing the fiddle. And Uncle Ed, he’d come up there to old man Joe Williamson’s home – that’s Molly’s dad – and he just played a lot for us and then us boys would play for him, me and Cecil would, and he’d show us a lot of things with the bow.”

Molly O’Day, I knew, was regarded by many as the most famous female vocalist in country music in the 1940s; she had retired at a young age in order to dedicate her life to the church.

“And he’s the one that told me all he could about old-time fiddling,” Snake continued. “He said, ‘Son, you’re gonna make a good fiddler, but it takes about ten years to do it.'”

I told Snake about reading in the Parkersburg Landing liner notes how Haley reportedly wished that “someone might pattern after” him after his death and he totally disagreed. He said, “I could have copied Uncle Ed – his type of playing – but I didn’t want to do it because he told me not to. He told me not to ever copy after anyone. Said, ‘Just play what you feel and when you get good, you’re as good as anybody else.’ That was his advice.”

I didn’t really know what to make of that comment. I mean, was Haley serious? Was he speaking from personal experience or was it just something he told to a beginning fiddler for encouragement?

After that, my conversation with Snake consisted of me asking questions – everything from how much Haley weighed to all the intricate details of his fiddling. I wondered, for instance, if Ed held the bow at the end or toward the middle, if he played with the fiddle under his chin, and if he ever tried to play words in his tunes. I wanted to know all of these things so that I could just inhabit them, not realizing that later on what were perceived as trivial details would often become major items of interest.

Snake answered my questions precisely: he said Haley held the bow “up a little in the middle, not plumb on the end” and usually played with the fiddle at his chest – “just down ordinarily.” He also said Haley “single-noted” most of his bow strokes, played frequently in cross-key, hated vibrato and used a lot of “sliding notes.” He seldom got out of first position, only occasionally “going down and getting some notes” that he wanted to “bring in the tune” and he definitely tried to play words in his music.

“The old fiddlers through the mountains here – and I guess it’s that way everywhere – they tried to make the fiddle say the words of the old tunes,” Snake said.

“Uncle Ed, he was a kind of a fast fiddler,” he went on. “Most old-time fiddlers are slow fiddlers, but he played snappy fiddling, kindly like I do. Ah, he could do anything with a fiddle, Uncle Ed could. He could play a tune and he could throw everything in the world in it if he wanted to or he could just play it out straight as it should be. If you could just hear him in person because those tapes didn’t do him justice. None of them didn’t. To me, he was one of the greatest old-time fiddlers of all time. He was telling me, when I was young, he said, ‘Well, I could make a fiddle tune any time I want to,’ but he said he just knowed so many tunes he didn’t care about making any more. He played a variety of tunes that a lot of people didn’t play, and a lot of people couldn’t play. He knew so many tunes he wouldn’t play one tune too long.”

I asked Snake about Haley’s repertoire and he said, “He played an old tune called ‘Old Sledge’ and it was one of his good ones. He played tunes like ‘Trouble Among the Yearlings’, but when he was gonna play it he called it ‘Fox in the Mud’. He made that up himself. One of the favorite tunes of mine he played was the old-time way of playing ‘Blackberry Blossom’ and he played it in G-minor. Ed could really play it good. They was somebody else that made the tune. Uncle Ed told me who it was – Garfield. He said he was a standing fiddling near a big blackberry patch and it was in bloom at the mouth of the hollow one time and this fella Garfield played this tune and he asked this fella Garfield what the name of the tune was. He said, ‘Well, I ain’t named it, yet,’ and he turned around and spit in that blackberry patch with a big bunch of ambeer and said, ‘We’ll just call it ‘Blackberry Blossom’.”

Snake laughed.

“Yeah, Uncle Ed, he had tales behind every one of them like that, but that’s where he said he got the name of it. He said he named it there…spitting in the blackberry blossom.”

Snake only remembered Haley singing “Stacker Lee”, a tune I’d heard him fiddle and sing simultaneously on Parkersburg Landing:

Oh Stacker Lee went to town with a .44 in his hand.

He looked around for old Billy Lyons. Gonna kill him if he can.

All about his John B. Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee entered a bar room, called up a glass of beer.

He looked around for old Billy Lyons, said, “What’re you a doin’ here?

This is Stacker Lee. That bad man Stacker Lee.”

Old Billy Lyons said, “Stacker Lee, please don’t take my life.

Got a half a dozen children and one sweet loving wife

Looking for my honey on the next train.”

“Well God bless your children. I will take care of your wife.

You’ve stole my John B. Stetson hat, and I’m gonna take your life.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

Old Billy Lyons said, “Mother, great God don’t weep and cry.”

Oh Billy Lyons said, “Mother, I’m bound to die.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee’s mother said, “Son, what have you done?”

“I’ve murdered a man in the first degree and Mother I’m bound to be hung.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

Oh Stacker Lee said, “Jailor, jailor, I can’t sleep.

Old Billy Lyons around my bedside does creep.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

Stacker Lee said, “Judge, have a little pity on me.

Got one gray-haired mother dear left to weep for me.”

All about that broad-rimmed Stetson hat.

That judge said, “Old Stacker Lee, gonna have a little pity on you.”

I’m gonna give you twenty-five years in the penitentiary.”

All about that John B. Stetson hat.

It was one awful cold and rainy day

When they laid old Billy Lyons away

In Tennessee. In Tennessee.

Snake said Haley used to play on the streets of Williamson, West Virginia where he remembered him catching money in a tin cup. In earlier years, he supposedly played on the Ohio River and Big Sandy boats and probably participated in the old fiddlers’ contests, which Snake’s father said was held on boat landings. These impromptu contests were very informal and usually audience-judged, meaning whoever got the most applause was considered the winner. Sometimes, fiddlers would just play and whoever drew the biggest crowd was considered the winner.

I asked Snake if he ever heard Ed talk about Clark Kessinger and he said, “Skeets was telling me Ed didn’t like Clark at all. He said, ‘That damned old son-of-a-gun stands around and tries to pick up everything he can pick up from you.’ And he did. Clark tried to pick up everything from Uncle Ed. He was a good fiddler, too.”

Snake said Clayton McMichen (the famous Skillet Licker) was Haley’s favorite fiddler, although he said he knew just how to beat him. This made me think of the line from Parkersburg Landing, “In regard to his own fiddling, Haley was not particularly vain, although he was aware that he could put ‘slurs and insults’ into a tune in a manner that set him apart from all other fiddlers.” (I wasn’t exactly sure he meant by slurs and insults.)

Snake could tell that I was really into Haley.

“Try to come see me and we’ll make you as welcome as we possibly can,” he said. “I tell you, my wife is poorly sick, and I have a little trouble with my heart. I’m 71. Doctors don’t want me to play over two or three hours at a time, but I always like to meet other people and play with them. I wouldn’t have no way of putting you up, but you can come any time.”

Just before hanging up, I asked Snake if he had any Haley recordings. He said Skeets Williamson had given him some tapes a few years back and “was to bring more, but he died two years ago of cancer.” Haley had a son in Ashland, Kentucky, he said, who might have more recordings. “I don’t know whether he’s got any of Uncle Ed’s stuff or not. See, most of them old tapes they made, they made them on wire recordings, and I don’t know if he’s got any more of his stuff than what I’ve got or not.”

I told Snake I would drive up and see him in the spring but ended up calling him a week later to ask him if he knew any of Ed’s early influences. He said Ed never talked about those things. “No sir, he never did tell me. He never did say. Evidently, he learned from somebody, but I never did hear him say who he learned from.” I felt pretty sure that he picked up tunes from the radio. “Ed liked to listen to the radio, preferring soap operas and mystery chillers, but also in order to hear new fiddle tunes,” the Parkersburg Landing liner notes read. “A good piece would cause him to slap his leg with excitement.” I asked Snake if he remembered Haley ever listening to fiddlers on the radio and he said, “I don’t know. He must have from the way he talked, because he didn’t like Arthur Smith and he liked Clayton McMichen.”

What about pop tunes? Did he play any of those?

“He played ragtime pretty good in some tunes,” Snake said. “Really you can listen to him play and he slides a little bit of ragtime off in his old-time fiddling – and I never did hear him play a waltz in all the time I ever heard him play. He’d play slow songs that sound old lonesome sounds.”

Snake quickly got into specifics, mentioning how Haley only carried one fiddle around with him. He said, “He could tune right quick, you know. He didn’t have tuners. He just had the keys.”

Did fiddlers tune low back in those days?

“I’d say they did. They didn’t have any such thing as a pitch-pipe, so they had to tune just to whatever they liked to play.”

Haley was the exception.

“Well, it seemed like to me he tuned in standard pitch, I’m not sure. But from hearing his fiddling – like we hear on those tapes we play now – I believe he musta had a pitch-pipe at that time.”

I wondered if Haley spent a lot of time messing around with his fiddle, like adjusting the sound post, and Snake said, “No, I never did see him do that. He might have did it at home but when he was out playing he already had it set up the way he wanted to play.”

Surprisingly, Snake didn’t recall Haley playing for dances. “I don’t think he did because I never did know of him playing for a dance. He was mostly just for somebody to listen to, and what he did mostly was to make money for a living playing on the street corner. I seen him at a fiddling contest or two – that was back before I learned to play the fiddle. That’s when I heard him play ‘Trouble Among the Yearlings’. He won the fiddling contest.”

What about playing with other fiddlers?

“Well, around in this area here he was so much better than all the other fiddle players, they all just laid their fiddles down and let him play. The old fiddlers through here, they wasn’t what I’d call too good fiddlers. We had one or two in the Pikeville area over through there that played a pretty good fiddle. Art Stamper’s dad, he was a good old-time fiddler, and so was Kenny Baker’s dad.”

After hanging up with Snake, I gave a lot of thought to Haley reportedly not liking Arthur Smith. His dislike for Smith was documented on Parkersburg Landing, which stated plainly: “Another fiddler he didn’t care for was Arthur Smith. An Arthur Smith record would send him into an outrage, probably because of Smith’s notoriously uncertain sense of pitch. Cecil Williamson remembers being severely lectured for attempting to play like ‘that fellow Smith.'”

Haley probably first heard Smith over the radio on the Grand Ole Opry, where he debuted in December of 1927. Almost right away, he became a radio star, putting fiddlers all over the country under his spell. His popularity continued to skyrocket throughout the 1930s, during his collaboration with Sam and Kirk McGee. In the late thirties, Haley had a perfect chance to meet Smith, who traveled through southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky with the Tennessee Valley Boys. While unlikely, Haley may have met him at fiddling contests during the Depression. “In the thirties, Haley occasionally went to fiddle contests to earn money,” according to Parkersburg Landing. At that same time, Smith was participating in well-publicized (usually staged) contests with Clark Kessinger, Clayton McMichen and Natchee the Indian. Haley, however, tended to avoid any contest featuring Natchee the Indian, who “dressed in buckskins and kept his hair very long” and was generally a “personification of modern tendencies toward show fiddling.”

In the early 1940s, Haley had a perfect opportunity to meet Smith, who appeared regularly on WSAZ’s “Tri-State Jamboree” in Huntington, West Virginia. Huntington is located several miles up the Ohio River from Ashland, Kentucky and is West Virginia’s second largest city.

In the end, Haley’s reported low opinion of Smith’s fiddling was interesting. Arthur Smith was one of the most influential fiddlers in American history. Roy Acuff regarded him as the “king of the fiddlers,” while Dr. Wolfe referred to him as the “one figure” who “looms like a giant over Southern fiddling.” Haley even had one of his tunes – “Red Apple Rag” – in his repertoire. Maybe he got a lot of requests for Smith tunes on the street and had to learn them. Who knows how many of his tunes Haley actually played, or if his motives for playing them were genuine?

Writings from my travels and experiences. High and fine literature is wine, and mine is only water; but everybody likes water. Mark Twain

This site is dedicated to the collection, preservation, and promotion of history and culture in Appalachia.

Genealogy and History in North Carolina and Beyond

A site about one of the most beautiful, interesting, tallented, outrageous and colorful personalities of the 20th Century