Tags

Devil Anse Hatfield, genealogy, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Logan, Logan County Banner, Oakland House, West Virginia

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 13 April 1893.

20 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Logan

Tags

Devil Anse Hatfield, genealogy, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Logan, Logan County Banner, Oakland House, West Virginia

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 13 April 1893.

20 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in African American History, Civil War

Tags

Appalachia, civil war, Confederate Army, Cumberland Mountains, David Stuart Hounshell, E.H. Perry, From Youth to Old Age, history, James Stephens, John B. Floyd, Kentucky, King Salt Works, Louis Bledsoe, Prestonsburg, slavery, Thomas H. Perry, Virginia

About 1910, Rev. Thomas H. Perry reflected on his long life, most of which was spent in the vicinity of Tylers Creek in Cabell County, West Virginia. In this excerpt from his autobiography, Mr. Perry recalled his participation in Civil War activity in eastern Kentucky and southwest Virginia.

After the night fight, above Prestonsburg, we knew the Federals were above us and we would have to fight if we ever got back to Dixie. The cold weather and deep snow and timber across the road and Federals to contend with, we moved very slowly. One morning we stopped, as I thought for breakfast, and as I was almost frozen I rejoiced because I thought we will all get warm and some beef, as I saw one man shoot down a cow. But just at that time the Federals run in our pickets and began shooting at us, but I was so hungry I ran to the cow and cut two or three pounds out of the hind-quarter and took it with me. We ran about one mile and there we saw Colonel Hounshal’s regiment in battle line, who held the Federals off us until we could get our breakfast. I took my beef without salt and put it on the end of my ramrod and held it to the fire and cooked an ate it, and it was good.

The next day my company was the rear guard and it was reported to the captain that the Federals had got between us and our command. The captain said: “Men, we will have to fight or we will be taken prisoners.” There was a preacher with us that day. He said: “Captain, I did not intend to fight, but rather than be a prisoner I will fight. Give me a gun.” When I saw him shoulder his gun, it did me good. I thought if a preacher could fight it was not bad for me to fight, as I was only a prospective preacher.

One very cold night I was detailed on the outer picket post, the orderly said: “You can not have fire as they are likely to slip upon you and shoot you.” I said to the orderly: “I cannot stand it without fire.” I thought I would freeze to death. The orderly said: “I cannot excuse you.” Just at that time Louis Bledsoe said to the orderly he could stand more cold than Perry could and he would go in my place and I could go in his place some other time. Never did I forget the kindness Mr. Bledsoe showed me that night.

When we were within fifteen miles of the Cumberland mountains, our army cattle, prisoners and all we had was on one creek; that creek led to the main road across the mountains into Dixie. On either side of this creek, the mountains were high and very rough and covered with snow. The Federals cut timber across the creek above us, and had a strong army below us, and held us here three days and would have captured us and all we had if General Floyd had not come with his artillery and drove the Federals away from the head of the creek, and let us out. The first night after we crossed the mountain into Dixie, E.H. Perry, one of my brothers came to my captain’s tent and said: “Captain, are my brothers all here?” He said: “Yes.” Then my brother exclaimed: “Thank the Lord for that.” Never will I forget the tone of my brother’s voice that night for he knew we had been gone for forty-one days, and it was by the hardest work that we landed back in Dixie.

Once more after this we went into winter quarters near the King Salt works, and they sent me to a farm house to nurse three sick soldiers. We had a large nice room, well furnished and the landlord was rich and good to us. He and his good wife would help me in waiting on the sick; he furnished us with everything we could ask for to eat. We stayed there more than three months. I saw in the beginning that I would not have much to do, and as I had the money and there was a book store at that place, I bought a complete set of school books and studied them hard that winter and it did me good. It helped me to keep down the roughness of a soldier’s life, and also to educate. Along the back yard there was a row of one-story brick buildings in which the negroes lived. Some nights I would go and hear them tell ghost stories, and they knew how to tell them for they had seen a great many ghosts. I deny superstition, but I noticed when these negroes had told me some of the most fearful ghost stories, if it was a very dark night I would ask some of them to go apart of the way home with me.

Mr. James Stephens, one of my patients, died; the other two got well. We left that place about the first of May. I saw then that the south could not gain her independence, and I told these negroes I thought they would soon be free and advised them to learn to read and write. I talked with a good many old men in the south about the war. They said they should have raised the “Old Flag” and contended for the constitution, and as for slavery, they said it was dying out in the south anyway.

Source: From Youth to Old Age by T.H. Perry, Chapter 8, p. 20-22.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Hatfield-McCoy Feud

Tags

Appalachia, crime, Devil Anse Hatfield, Hatfield-McCoy Feud, history, Island Creek, Logan, Logan County, Logan County Banner, West Virginia

Logan County Banner (Logan, WV), 28 March 1889.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in African American History, Coal, Native American History

Tags

Adirondack Mountains, Allegheny Mountains, Appalachia, Blue Ridge Mountains, Chattanooga, Chattanooga Times, Cherokee, Choctaw, culture, history, Huntington, Huntington Advertiser, indentured servants, Native Americans, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, slavery, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia

On July 15, 1896, the Huntington Advertiser of Huntington, West Virginia, printed a story titled “The Poor Whites: Origin of a Distinct Class Living in the South.” Subtitled “The ‘Cracker of the Hills’ is the Direct Descendant of the ‘Sold Passengers’ Who Came to This Country in the Seventeenth Century,” the story initially appeared in the Chattanooga Times of Chattanooga, Tennessee. And here it is:

The notion that the poor white element of the southern Appalachian region is identical with the poor people generally over the country is an error, and an error of enough importance to call for correction. The poor white of the south has some kinfolk in the Adirondack region of New York and the Blue and Alleghany [sic] mountains of Pennsylvania, but he has few relatives any place else about the Mason-Dixon line. The states of New York and Pennsylvania were slave states until the early part of this century.

This poor white mountaineer descends direct from those immigrants who came over in the early days of the colonies; from 1620 to about or some time after the Revolutionary war period, as “sold passengers.” They sold their services for a time sufficient to enable them to work out their passage money. They were sold, articled to masters, in the colonies for their board and fixed wage, and thus they earned the cost of their migration.

The laws under which they were articled were severe, as severe as apprentice laws in those days. The “sold passenger” virtually became the slave of the purchaser of his labor. He could be whipped if he did not do the task set [before] him, and woe to the unlucky wight [sic] if he ran away. He was sure to be caught and cruelly punished.

And though he was usually a descendant of the lowest grade of humanity on the British islands, he still had enough of the Anglo-Saxon spirit about him to make him an unsatisfactory chattel.

From 1620 forward–the year when the Dutch landed the first cargo of African slaves on the continent–the “sold passenger” was fast replaced by negroes, who took more naturally and amiably to the slave life.

The poor white naturally came to cherish a bitter hatred for the blacks that were preferred over him. He already hated his domineering white master. When he was free to go, he put as many miles as his means and his safety from Indian murderers permitted between himself and those he hated and hoped he might never see again. In that early time the mountain region was not even surveyed, let alone owned by individual proprietors.

The English, Scotch, Irish and continental immigrant who had some means sat down on the rich valleys, river bottoms and rolling savannahs, and the poor white was made welcome to the foothills and mountain plateaus.

These descendants of the British villain of the feudal era grew and multiplied, became almost as distinct a people from the lords of the lowlands as the Scotch highlander was, as related to his lowland neighbor, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The stir of the period since the close of our civil war has made somewhat indistinct the line that separates the mountaineer from the plainsman of the south, especially in the foothills and at points where the two have intermingled in traffic, in the schoolhouse and church, and especially where the poor whites have been employed at mining, iron making, etc. But go into the mountains far enough and you will find the types as clear cut as it was 100 years ago, with its inimitable drawling speech and curious dialect, its sallow complexion, lanky frame, lazy habits and immorality–all as distinctly marked as they were when hundreds of these people found Cherokee wives in Georgia and Tennessee in the early part of the century and bleached most of the copper out of the skin of the Choctaw as well as out of the Cherokee.

It is a pity that some competent anthropological historian has not traced the annals of this interesting and distinctive section of our population, and made record of it in the interest of science, no less than in the interest of the proper education and elevation of the mountain people. It has become, especially in the Piedmont section of the south, a most important labor element. The cotton mill labor by thousands comes from the “Cracker of the Hills,” and it is destined o become a great power, that labor population, social and political.

The redemption of the poor white began when slavery went down in blood and destruction, and it has gone on faster and traveled further than some of us think.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Native American History

Tags

Appalachia, Ashland, Boyd County, Central Park, history, Kentucky, Mound Builders, Native Americans, photos

Central Park, Ashland, Boyd County, KY. April 2016.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Civil War

Tags

Appalachia, Battle of Big Ugly Creek, Big Ugly Creek, Cabell County, Chapmanville, civil war, Confederate Army, From Youth to Old Age, Guyandotte River, Hamilton Fry, history, Kentucky, Lincoln County, Logan County, Mason County, Prestonsburg, Six Mile Creek, T.E. Ball, Thomas H. Perry, Union Army, Virginia, Wayne County, West Virginia, William Jefferson

About 1910, Rev. Thomas H. Perry reflected on his long life, most of which was spent in the vicinity of Tylers Creek in Cabell County, West Virginia. In this excerpt from his autobiography, Mr. Perry recalled his participation in Civil War skirmishes at the Forks of Ugly and Six Mile Creek in present-day Lincoln County, WV, and military activity around Prestonsburg, Kentucky:

In 1862 my company was ordered to move from Chapmansville down the Guyan river. About three o’clock that day we ran into a company of Federal soldiers at the forks of Big Ugly creek, and as neither company was expecting trouble at this time, we were not ready for the fight, but our captain ordered his men in line, and we marched around the hillside, fronting the creek, and the Federals formed a line up the creek, fronting us. Here we tried our bravery for a few minutes, but as we had the advantage of some timber, the Federals broke ranks and went into the woods, except ten or twelve that lay flat upon the ground, and we captured them, and all the rations the company had, such as coffee and sugar, which was a treat for us in that country. About this time another company came up and followed the Federals into the woods. I never knew what became of them until after the war. Mr. T.E. Ball, of Mason county, told me after the war that he was a member of that company of Federals, and he was in the fight at the forks of Big Ugly, and that he was in the closest place that day of any time during the war. he said he was certain there were more than fifty shots fired at him as he ran through the field, and of the eighty-four men in his company, there was not a man that returned with his gun, and but few that had hats or shoes, for they were scattered in the woods and every man looked out for himself. The next day, we had six men in the advance guard. I was one of them, and as we turned the point at the mouth of Six Mile creek, six miles above the falls of Guyan river, we ran into a squad of seven Federal soldiers, who fired into us and killed William Jefferson, one of our bravest soldiers.

The next day we crossed the river at the falls of the Guyan and went through Wayne county into Kentucky. Here we were fired into every day and night for about three weeks. It was December and we had some very cold weather. Several times I have seen men and horses lying on the side of the road frozen so stiff they could not travel.

We had about fifteen hundred men with us at that time. We had several hundred prisoners and a great deal of army supplies that we had captured, and the cold weather and the Federals and so many bushwhackers to contend with, that we had no rest day or night. Just below Prestonsburg we captured seven flat boats that were loaded with army supplies, such as clothing and food, and many of us needed both, but we paid dearly for them, for many of our men on both sides lost their lives in this fight. For two hours and thirty minutes they poured the hot lead into each other as fast as they could. The battle lines of both armies extended from the river to the top of the mountain. I was on top of the mountain when the Federals broke rank. Our major ordered his men to go down both battle lines and gather up the dead and wounded and take them to the foot of the mountain.

I went down the Federal battle line in front of our men, and when I saw the dead and wounded and the guns and blood and clothing that was scattered from the top to the bottom of that mountain, I was perfectly disgusted with war. About half way down this line we found their major; he was shot through the heart. He was a nice looking gentleman; he had a long black beard. Our men seemed to have great respect for his body, because he was an officer, and gave special directions for his burial. Some of the prisoners cried aloud like children, while others cursed and said they were see every rebel in hell before he would cry. Just how many men we had killed and wounded in this fight I never knew. Some of our wounded we took with us, and some was so badly wounded we left them in private homes. From this places we turned to the south for winter quarters. My company was the rear guard that night. We thought the rear guard would suffer more than any other part of the army, but to our surprise after we had gone a few miles above Prestonsburg we heard considerable shooting and disturbance in our front about two miles from us. It was a very dark night, and when my company came up to about where we thought the shooting was, we heard horses and men groaning. After we had gone about two miles farther, we went into camp until morning. That morning one man told me one of our men that was killed last night lived in Parkersburg. The great question with us at this time was, can we ever get back to Dixie with our cattle, goods and prisoners? The Federals were above us and below us.

Source: From Youth to Old Age by T.H. Perry, Chapter 7, p. 18-20.

Note: As of 1862, Lincoln County did not exist and the surrounding area remained a part of Virginia. Big Ugly Creek was then located in Logan County and Six Mile Creek was located in Cabell County.

Note: The “forks of Ugly” references the mouth of Laurel Fork, at or near the old Hamilton Fry homeplace.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Lincoln County Feud

Tags

Appalachia, author, book, books, Brandon Kirk, Greenbrier County, Lewisburg, Lewisburg Literary Festival, Pelican Publishing Company, West Virginia

Lewisburg Literary Festival in Lewisburg, WV. 6 August 2016. Photo by Mom.

18 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Chapmanville, Civil War

Tags

Appalachia, Chapmanville, Charleston, civil war, George W. Workman, H.J. Samuels, history, Jacob D. Cox, Union Army, Virginia, West Virginia, Wheeling

The following letter from Jacob D. Cox dated December 11, 1861 at Charleston, Virginia, to Adjutant General H.J. Samuels in Wheeling, Virginia, offers insight into war conditions in Chapmanville, Logan County.

Charleston, Va. 11 Dec 1861

Sir:

Geo. W. Workman, residing at Chapmansville, Logan Co. is represented to me by reliable parties as a reliable loyal man, & I have confidence in the representation. He desires authority to raise a company of home guards to protect that vicinity when marauding bands are doing mischief from time to time. Will you please give such authority as may be needed to enable him to organize a company & get it armed etc.

Very truly,

Your obedient servant,

J.D. Cox

Source: Adjutant Generals’ Papers, Union Militia 1861-1865, Ar 373, Letters, Logan County. West Virginia State Archives, The Culture Center, Charleston, WV.

17 Saturday Sep 2016

Posted in Logan

Tags

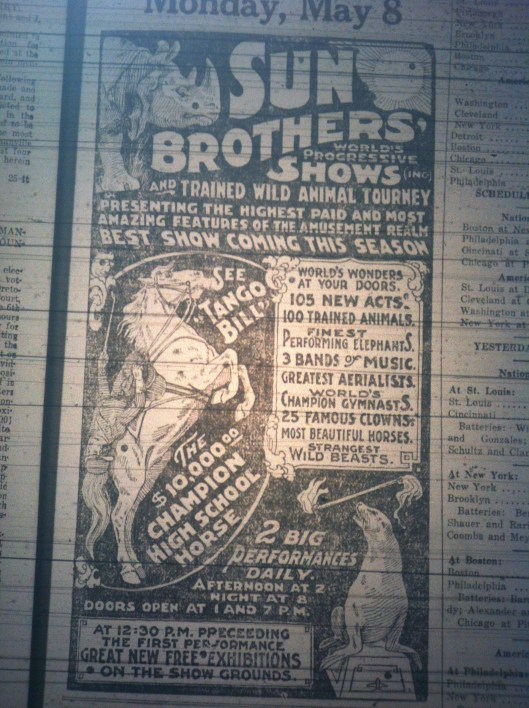

Appalachia, circus, history, Logan, Logan County, Logan Democrat, Sun Brothers, Tango Bill, West Virginia

Logan (WV) Democrat, 4 May 1916.

17 Saturday Sep 2016

Tags

Appalachia, Bill Smith, Ceredo, Confederate Army, history, John Adams, Ohio River, Union Army, Wayne County, West Virginia, West Virginia Adjutant Generals Papers

The following letter from John Adams dated October 5, 1863 at Ceredo, WV to Governor Arthur I. Boreman offers insight into war conditions in Wayne County, WV.

Ceredo, W.Va.

Oct. 5, 1863

Rebel Capt. Bill Smith with about 175 men made a raid into Wayne Co. this last summer with the avowed purpose of pressing horses. He passed thro our Co. one way & returned another, coming entirely to the Ohio River. He took all the horses he could from the Union men, even those that were very old & poor. But at the premises of Secessionists, he posted guards. The facts now are the Secessionists ride about the county on their good horses & the Union people walk! They deride our new State & Government, never vote, but secretly assist all rebel raids. They can stay & live at home securely while our Union people hide about where they can. As the case is now in our Co. the Secessionists are secure on their farms, secure their crops, ride good horses, make money & in fact appear to be Lords of this Country. How long do you think the Union men here will endure this state of affairs? They are beginning to think that the Rebels ought to have different rights to what they now enjoy in the Co. We want all Rebels & their assistants hung or Sent out of our Co. never to return. Please write to us. I remain yours.

Source: West Virginia Adjutant Generals’ Papers, Union Militia 1861-1865, Ar 373, Box 28, Wayne County, Folder 2. Located at WV State Archives, The Culture Center, Charleston, WV.

13 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in Logan

Tags

advertisement, Grape Smash, history, Logan, Logan Baking & Bottling Company, Logan Democrat, pop, soda, West Virginia

Logan (WV) Democrat, 13 July 1916.

13 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in Civil War, Huntington

Tags

Appalachia, civil war, history, hunting, Huntington, Huntington Advertiser, West Virginia, whisky

“The cold weather of a few days ago reminded me of a little adventure that I had while soldiering,” said a well known business man. “It was on New Years day 1863, and we camped at the foot of a West Virginia mountain. The snow was several inches deep and the cold was intense. There wasn’t much discipline, and as we were allowed to hunt some, I took my gun and started up the mountain side. I had gone half a mile probably, when I stopped at the foot of a tree. My hands were nearly frozen and I leaned my gun against the tree and commenced rubbing my hands together to warm them, when suddenly I heard the brush cracking and turning I beheld a huge bear coming in my direction. It was on its hind legs with its huge paws outstretched and its jaws open and I could almost feel its warm breath on my cheek. Recovering from my fright I sprang up and caught a limb of a tree, drawing myself up out of the way just in time to avoid the embrace of the huge beast. My heart thumped so it shook my whole body. The bear cantered around the tree, sniffling at my gun, which still stood leaning against it. I shouted until I was hoarse, hoping to attract some of the soldiers in camp, but to no avail. I fixed myself as comfortably as possible in the branches of the tree, and watched the bear, believing that he would soon tire and leave. The cold was terrific. My whole body was benumbed, and I wondered how much longer I could endure the cold before I would tumble out of the tree to be devoured by the bear. Suddenly a bright thought struck me, and descending to the lower branch I took a bottle of whisky from my pocket and began pouring a thin stream down into the barrel of my gun. The whisky striking the cold gun barrel froze and in a few moments there was a solid streak of frozen whisky reaching from the gun clear up to the bottle that I held in my hand. Taking hold of the whisky icicle, I carefully drew the gun up, hand over hand, until it was in my grasp. Then taking careful aim, I sent a bullet crashing into a vital spot of the bear, and it rolled down the mountain side dead. I hurriedly descended and found my way back to camp nearly frozen. Some people may tell you that whisky won’t freeze, but then it did in this instance, for it was the coldest day I ever experienced. Get a pension? Why certainly for I have never fully thawed out since that terrible freezing I got while clinging to that tree.”

Source: “Get A Pension Now,” Huntington (WV) Advertiser, 16 February 1899.

13 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in Culture of Honor, Hatfield-McCoy Feud

Tags

Appalachia, Elias Hatfield, George W. Atkinson, history, Huntington, Huntington Advertiser, Mingo County, West Virginia

Huntington (WV) Advertiser, 11 July 1899.

13 Tuesday Sep 2016

Posted in Barboursville, Civil War, Hamlin

Tags

1st Regiment Virginia State Line, Abbs Valley, Ball Gap, Barboursville, Big Sandy River, Cabell County, civil war, Clint Lovette, Coal River, Confederate Army, G.W. Hackworth, Guyandotte, Guyandotte River, Hamlin, history, J.C. Reynolds, John B. Floyd, Kanawha River, Levisa Fork, Mud River, Mud River Bridge, Ohio, Proctorville, Thomas H. Perry, Tug Fork, Tylers Creek, Van Sanford, Virginia, West Virginia

About 1910, Rev. Thomas H. Perry reflected on his long life, most of which was spent in the vicinity of Tylers Creek in Cabell County, West Virginia. In this excerpt from his autobiography, Mr. Perry recalled the early years of the Civil War in his locale:

Immediately after our first defeat we began to plan for another exit to Dixie, as so few of our men made their escape to Dixie after being fired into at the falls of Guyan, for we knew now for a certainty that we must go south and be a soldier or go north a prisoner; for the Federals were going through the country picking up men and sending them away as far as they could. This last plan was for us to meet at Ball Gap, on Mud river, early in the morning, and a company of armed men would meet us there to guard us out to Dixie. Early that morning I met thirty or forty young men at the Ball Gap. We appointed G.W. Hackworth as our leader, and we moved on Mud river, and the young men came to us all along the way, and when we arrived six miles above Hamlin, we had from one to two hundred men in our company. From there we crossed the mountain to the Guyan valley, and then up the river and over the mountains and through the woods for ten days and nights, and we found ourselves in Aps [sic] valley, Virginia. Here we organized a military company* by electing G.W. Hackworth, captain; Van Sanford, J.C. Reynolds and Clint Lovette, lieutenants. No one knows but myself the feelings I had the day I took the oath to support the constitution of the Southern Confederate States of America and to discharge my duty as a soldier. As they swore me they handed me a bible. I remembered that this is the book that I had been preparing myself to preach, and it says: “Thou shalt not kill,” and it gave me trouble as long as I was a soldier.

We drilled at this place two or three weeks, and had eighty-four men in our company, and they generally used us as scouts, operating from the Kanawha river westward, down into Kentucky and eastern Tennessee. There would be times that we would not see our regiment for two months, and then again we would be with them every day for two months. The Federals were trying to make their way up Coal river, Guyan river, Tug river, and the Levisa fork of Big Sandy river, in Kentucky. Their idea was to destroy the New river bridge and the King salt works. General Floyd had a brigade of soldiers somewhere about the headwaters of these rivers; sometimes he would send large scouting parties down these rivers and drive out everything before them. Sometimes when we would be driving them down one river they would be moving up some other river. I have crossed the mountains between these rivers so many times and was shot at by men in the brush and suffered from hunger and cold so many times that it makes me think of war as the darkest days of my life. At one time I went three days and nights without one bite to eat; in many places we had to live on the country that we were in, and the soldiers in front would get all the citizens had to eat, and the rear guard suffered for food; we did not have battles like Lee and Grant, but to many of our poor boys the battle to them was as great as that of Gettysburg or Cold Harbor was to some of them.

At one time my company and some other company was ordered to Cabell county, and we came to Mud river bridge and went into camp for eight or ten days at this place. During our stay in this camp we had no trouble in getting food for our horses and soldiers for the Reeces and Morris and Guinns and Kilgores and others who lived in this neighborhood had an abundance of this world’s goods at that time. One morning our captain said he wanted eight volunteers who would go afoot for three or four days; he had no trouble in getting the eight men; I was one of that number; Lieutenant Lovette was in command, and at noon that day we ate dinner near Barboursville, and at night we were in Guyandotte. Several times the next day we would stand along the river front and see the Federal soldiers in Proctorville. In the middle of that afternoon we started back for Mud river bridge, and the next day our command broke camp, and we started for Dixie. Why these eight men were sent to Guyandotte I never knew, and why General Floyd sent such large scouting parties to Mason, Cabell and Wayne counties, as he did at this time, I never knew, unless it was to give protection to those who were desirous of going south with their families and chattels, which a great many did, and stayed until after the war.

Source: From Youth to Old Age by T.H. Perry, Chapter 6, p. 16-18. Note: As of 1862, Cabell County remained a part of Virginia and Lincoln County did not exist.

*Company F, 1st Regiment Virginia State Line

11 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Dunlow, Lincoln County Feud

Tags

Appalachian, Blood in West Virginia, books, Brandon Kirk, Cabwaylingo State Forest, Camp Anthony Wayne, Camp Twelvepole, Civilian Conservation Corps, Dunlow, history, Pelican Publishing Company, Wayne County, West Virginia

Cabwaylingo State Forest, located at Dunlow in Wayne County, WV, began in the 1930s as a CCC camp project. I recently introduced my book to the park. 20 August 2016. Photo by Mom.

11 Sunday Sep 2016

Posted in Boone County, Logan

Tags

Arthur I. Boreman, Boone County, civil war, Confederate Army, John A. Barker, justice of the peace, Logan, Logan County, Richmond, Thomas Buchanan, Union Army, Virginia, West Virginia

The following letter from Thomas Buchanan dated July 14, 1865 at Brownstown, WV to Governor Arthur I. Boreman offers insight into immediate postwar conditions in Logan and Boone counties, WV. The letter was titled “Enclosed account for services in recruiting a Co. of Scouts for Logan & Boone Counties.”

Brownstown

July 14, 1865

His Excellency A.I. Boreman (Governor)

Sir: I Rec’d an order dated March 2nd 1865 authorizing me to organize a company of State Guards for the counties of Logan and Boone to consist of not less than 25 men. At first I thought I could recruit 25 men in a short time, but I was much deceived. Men remaining in those counties at that time had bin [sic] conscripted in to the Confederate service (or what they called State line Service under the Confederate authorities) and had bin [sic] disbanded and they seemed to have taken up the idea (or a portion of them at least) that neutral ground was saftest for them, as the country was infested with bushwhackers, and sixty or seventy miles outside of federal lines I could get no assistance from federal troops and consequently had to scout alone and sometimes [with] one man for company. Finally I succeeded in recruiting 32 or 33 men, made off my muster Roll, called my men together, the required oath was administered to them by John A. Barker, a Justice of the Peace, and his certificate with the Roll and form of oaths was directed to the adjutant Gen’l of the State and I have not heard from it since tho when Richmond fell I did not expect my men would be armed and equipped tho I shall expect to be enumerated for my services to the State for recruiting the company.

Yours respectfully,

Thomas Buchanan

P.S. My address is Logan C.H., W.Va. I did not expect an answer to my muster Roll.

Source: West Virginia Adjutant Generals’ Papers, Union Militia 1861-1865, Militia Box 12, Logan County, Folder 2. WV State Archives and History, Charleston, WV.

Note: To see Mr. Buchanan’s account, follow this link: http://www.wvculture.org/history/wvmemory/militia/logan/logan02-01.html

10 Saturday Sep 2016

Tags

Appalachia, Brandon Ray Kirk, coal, history, Kermit, Marrowbone Creek, Mingo County, Norfolk and Southern Railroad, Norfolk and Western Railroad, photos, West Virginia

Norfolk & Southern Railway Tunnel No. 3, Marrowbone Creek, Mingo County, WV. 20 August 2016. Photo by Mom.

10 Saturday Sep 2016

Posted in Big Creek, Chapmanville

Tags

Appalachia, Big Creek, C.J. Shelton, Chapmanville, David Woods, genealogy, history, Hugh Butcher, John Dingess, Liza Conley, Logan, Logan County, Logan County Banner, Mary Chambers, Mary Dingess, Mary Stone, Nettie Cabell, Rocky School, West Virginia

An unknown local correspondent from Chapmanville in Logan County, West Virginia, offered the following items, which the Logan County Banner printed on October 16, 1897:

David Woods of Illinois is visiting friends at this place.

Miss Mary Stone, a bright little brunette, was calling on friends here Tuesday.

Mr. Hugh Butcher and Miss Nettie Cabell were quietly married on Big creek last Saturday.

Mrs. Dr. _____ visited her parents at Peck Sunday.

Miss Mary Chambers, one of Crawley’s charming belles, was calling on her many friends in this city last week.

Miss Mary Dingess is attending the Rocky school.

Madam rumor says that one of our old maids will soon leave the state of single blessedness for the sake of one of Big Creek’s most prominent widowers.

Miss Liza Conley and John Dingess were the guests of Dr. C.J. Shelton Monday.

Mr. and Mrs. Turley of Logan passed through the city Sunday.

10 Saturday Sep 2016

Posted in Lincoln County Feud

Tags

Appalachia, author, Blood in West Virginia, books, Brandon Kirk, Greenbrier College, Greenbrier County, John McElhenney, Lewisburg, Lewisburg Academy, Lewisburg Literary Festival, Lewisburg Seminary, Lincoln County Feud, Pelican Publishing Company, West Virginia

Many thanks to the Lewisburg Literary Festival for hosting us in Lewisburg, WV. 6 August 2016. Photo by Mom.

10 Saturday Sep 2016

Posted in Barboursville, Civil War, Salt Rock, West Hamlin

Tags

Appalachia, Barboursville, Bear Creek, Cabell County, civil war, Confederate Army, Enon Church, Falls of Guyan, genealogy, George Rogers, Guyandotte River, history, Lincoln County, Mud River, Salt Rock, South Carolina, Thomas H. Perry, Tylers Creek, Union Army, Virginia, West Virginia, William R. Brumfield

About 1910, Rev. Thomas H. Perry reflected on his long life, most of which was spent in the vicinity of Tylers Creek in Cabell County, West Virginia. In this excerpt from his autobiography, Mr. Perry recalled the early years of the Civil War in his locale:

In November, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union. That was more than a sign of war; it was a declaration of war. Soon afterwards six other southern states seceded, and a little later three other states followed suit, and last of all, in May, 1861, Virginia seceded.

My father said he had worked, prayed, voted for the Union, but he thought he owed his allegiance first to the state and then to the general government. However, he advised us boys to stay at home, as there are many things involved in this war and its hard to say what the outcome will be. One Sunday, in 1861, many of our young people were at Enon church, and at that time the union army was at Barboursville, ten miles away. While we were at church a man came on horseback in great speed with his hat off, and when he got to the church he cried out: “Get to the mountains; the Federals are on their way to Tyler’s creek, and are destroying everything before them.”

We all ran to the woods in great haste, and remained there until the next day, except the women and the children, who returned home that evening; the old men advised the women and children to stay at home, as they did not believe the soldiers would do them any harm. But several young men from this first scare, joined the Confederate army, but I stayed at home and dodged the soldiers until the spring of 1862. During this time I thought of going north and going to school, and then I would think if I went north they would force me to join the army and I would have to fight my own people, and I could not do that. I thought if I was in the south I could not go to school; they would force me in the army and I knew I could not stay at home. So I decided as there was no neutral ground for me I would go to Dixie. At this time the Federals were scouting the country in every direction which made it difficult to go, but we set a time to meet in a low gap east of Joseph Johnson’s, a half-way place between Guyan and Mud rivers. That night we filled that gap more than full of men and horses. It was a dark night and we never knew how many men we had present, but think there were two or three hundred. We were suspicious of traitors among us that night. We did our work quickly, appointed a captain and mapped out our way for that night’s march. The way was down Tyler’s creek to the Salt Rock and then up the Guyan river. About midnight our captain said: “Gentlemen, follow me,” and as we slowly moved out of that gap it was whispered, “we do not know whose hands we are in , as there are so many more here tonight than we expected, and so many strangers.”

When we came to where my father lived on Tyler’s creek, I asked George Rogers, a man of our company to wait with me until I could go to the barn and get my horse, for I had left my horse in the barn until we were ready to march. This delayed me about twenty minutes. Mr. Rogers and I thought we would soon overtake our men, but when we came to a bridle path that led to the mouth of Bear Creek, much nearer than by way of Salt Rock, it was so dark we could not see the track of a horse, and as we did not know which way our men had gone we were much perplexed and lost some time at this point, but decided to go the nearer way, and when we came within one mile and a-half of the falls of Guyan, we heard considerable shooting in our direction, and as our men were twenty-five or thirty minutes in the advance of us, the shooting must have been at our men, and as our men were not armed the shooting was all from one side and it may be that half of our men are killed. we stopped and decided that we would wait for daylight. We hitched our horses about fifty yards from the road and lay down under a beech tree that stood about twenty-five yards from the road, and we went into a doze. Suddenly, in front of us, there was a moving army and we could not tell whether they were going up or down the road until the rear guard passed, and then we knew they were going down the road. While they were passing, I said: “George, these are our men.” George said: “Be still, say nothing.”

When morning came, Mr. Lucas, a man living in that neighborhood, said to us: “The men that have just passed down the road killed Mr. Brumfield and had fired into a body of unarmed men at the falls just before day, this morning.” We understood the rest and at noon that day we were back again at my father’s house.

Source: From Youth to Old Age by T.H. Perry, Chapter 5, p. 14-16. Note: As of 1862, Cabell County remained a part of Virginia and Lincoln County did not exist.

Writings from my travels and experiences. High and fine literature is wine, and mine is only water; but everybody likes water. Mark Twain

This site is dedicated to the collection, preservation, and promotion of history and culture in Appalachia.

Genealogy and History in North Carolina and Beyond

A site about one of the most beautiful, interesting, tallented, outrageous and colorful personalities of the 20th Century